How do you train men to prepare them for war?

How do you train them when you have to expend your armed forces roughly one hundredfold? And how do you do this when you have to do it while you are fighting a global conflict?

I believe the answer inevitably will contain “compromises” and even “cutting a few corners”. In my opinion, the men who were affected by this the most were the men assigned as company aid men. They were trained as “jack of all trades” when they needed to be “a master of one”.

These unsung heroes had to do a lot of on the job training and innovation to save as many lives as possible. And they had to do it under some of the most difficult circumstances.

“Dave and I were busy bandaging wounds from rifle fire and trying to hold together extremities blown apart by cannon and mortar fire. Had it not been for the shock of the severity of the injuries we saw, we probably would not have been able to function. The shear horror of bodies ripped open and others blown apart made us numb, and we practiced our limited medicine as if we were only butchers looking at cut meat in our shop.

Neat, clean wounds do not happen to men in war. Wounds are gross, smashing, tearing, and ripping. What does one do with that part of a limb that is still attached to the body, but only by a thin string of flesh? Cut it loose or splint it to the body and hope for an evacuation miracle? How does one bandage a face that is missing a jaw? We did what we had to do and hoped that it was the right thing when, and if, we had time to think about it later. In the mean-time, we bandaged, injected morphine, and wondered at the miracle of the human body in its struggle to survive the ravages of hell. The smell of burned flesh is something I never forgot; the sight of more blood than I knew the human body could hold spread out over and around an amputee’s body is startling, frightening, and sickening at the same time. There is the smell of death; the smell of steaming body fluids as they escape from the body into the cold air and are replaced by death. Raw brutality taught me to ignore what I did not want to see, smell or hear—the worst of which are the gurgling sounds that flow from a dying man. And, as I left each casualty, I hoped that litter bearers would arrive in time to evacuate them before capture or death. You move on, there are more wounded to treat. Combat commands your undivided attention, and we did not have the luxury or time to think about what we were experiencing. That came later, generally at night, and most often during whatever quiet time we were blessed with”. “Medic!”a WWII combat medic remembers. Robert L. Smith (page 85-86)

In this blog, part 2 of the medical evacuation and treatment series, I will take an in-depth look at the company aid men.

Company aid man

So, what is a company aid man exactly? This is not as easy to answer as it might seem. First of all, you will not find company aid man in any TO&E (US Army Armored Division 1943-1945 – Yves Bellanger). Not in the combat units and not in any medical unit. Secondly, they were a part of the medical detachment administratively but served with the combat units. Depending on how you look at it you could say they were a part of two units, or they were not really a part of either unit.

So from an administrative point of view, we will find the company aid men in the TO&E of the medical detachments. It turns out that the company aid men were MOS 861: surgical technician. They were assigned by the battalion surgeon to the companies of the battalion. In an infantry division, they were assigned based on one company aid man/ surgical technician per platoon.

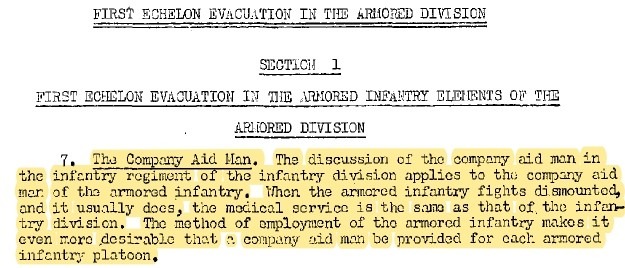

In an armored division, this was slightly different, depending on the type of unit.

According to US Armored Divisions 1943-1945, the medical detachments assigned one ¼-ton truck with two surgical technicians to all companies in all types of combat units.

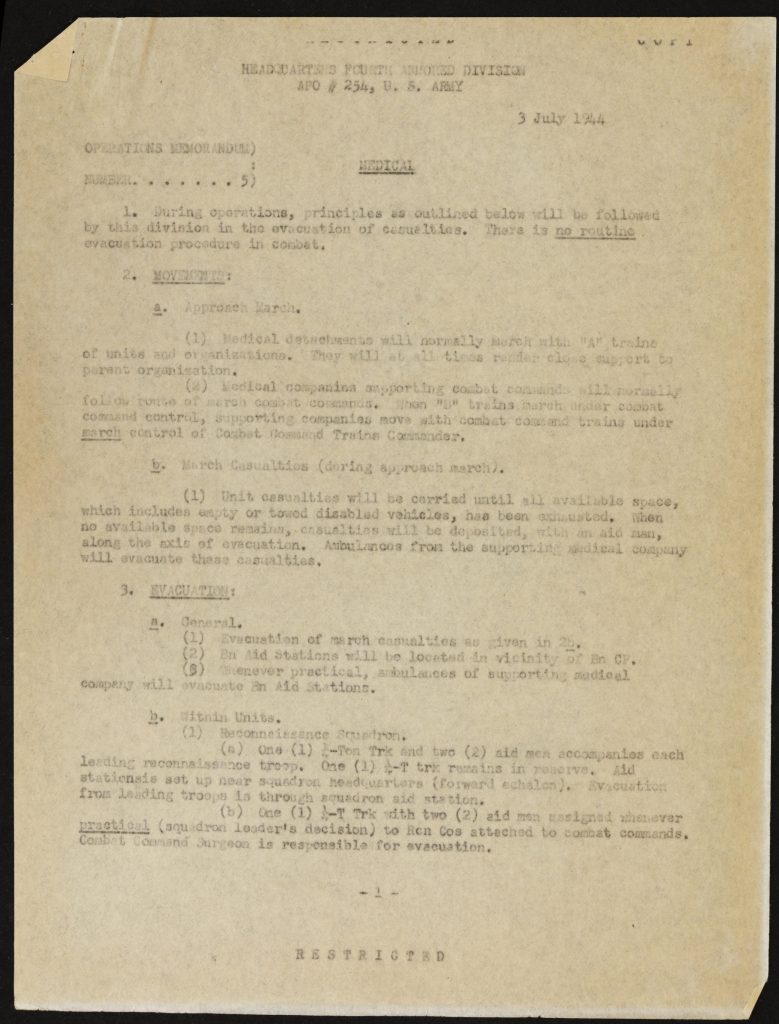

The 4th AD Division Surgeon, Lt.Col. Morris Abrams, wrote in the document Operations Memorandum (3 July 1944):

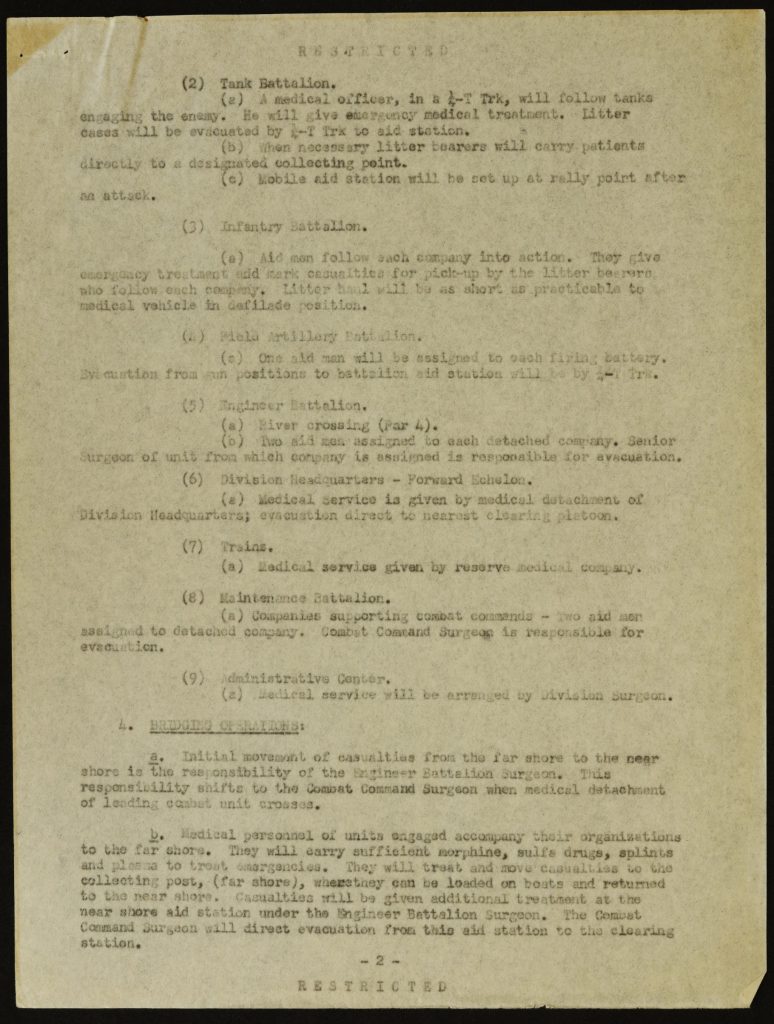

In a handwritten document, he wrote as preparation for a lecture, he further specified this, showing how the distribution of company aid men was in the combat units of the 4th AD:

Company aid man’s duties

What was the company aid man’s job? Well, according to this article on the website of the WW2 US Medical Reseach Center his duties were to:

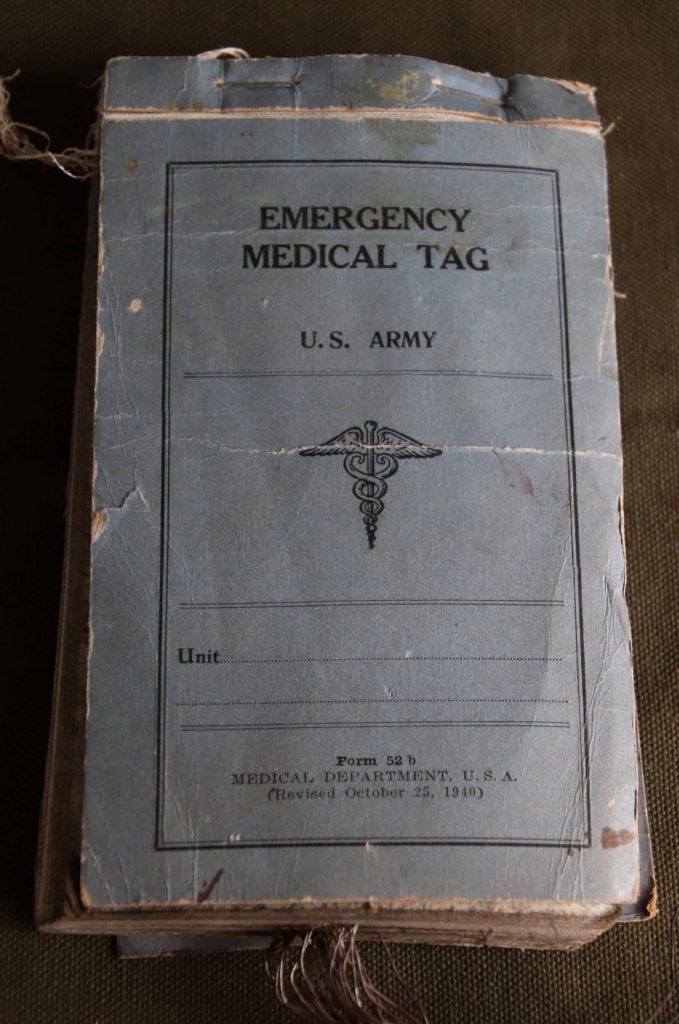

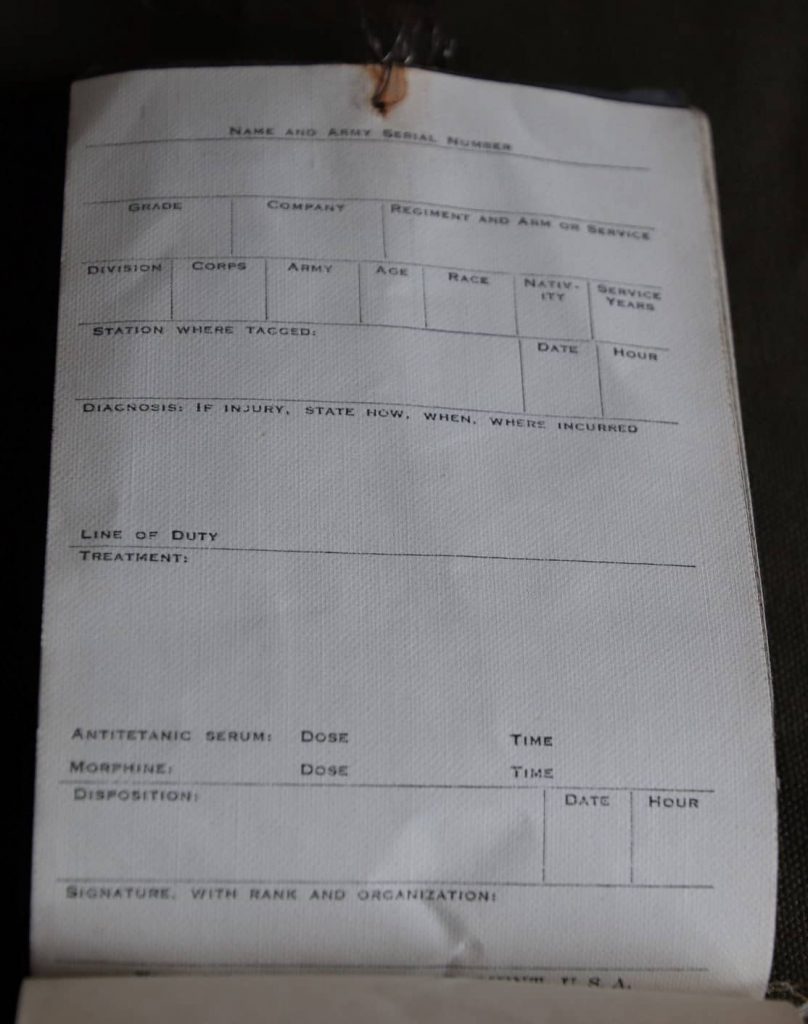

“Give emergency medical treatment either on or off the battlefield. Group the casualties in marked and protected places to await arrival of litter bearers. Direct the walking wounded to the Aid Station. Keep the Battalion Surgeon informed of the overall medical situation by means of messages carried back by Litter Squads or walking wounded. Fill out and attach the required Emergency Medical Tags, for wounded and dead when time and the tactical situation permitted this.”

Emergency medical treatment

Clearly, emergency medical treatment was the most important duty.

According to FM 21-11 Basic Field Manual – First Aid for Soldiers (April 7, 1943) all treatment of casualties by non-medical personnel was called first aid. Any treatment by medical personnel was called emergency medical treatment.

This distinction suggests a different treatment of casualties based on more extensive training and more equipment available to the medical personnel. Truth is: it was often the exact same basic treatment. And just as often the training was only slightly better than the average soldier.

“No doctor ever talked to us about treating wounds (probably because no one had been in combat). We once got instruction about pressure points and the use of tourniquets to control bleeding, but we were given no training in using the medicine and bandages that would eventually be in our medical pouches. I was transferred in grade (corporal T-5) to a medical unit with the 45th-still totally unqualified as a medic. I went into combat completely unprepared for the job I was supposed to know. Though I was called a medical corporal technician, I’d been taught nothing about taking care of combat wounds.

After we arrived in North Africa in June 1943, a couple of squads from the 36th Division gave my regiment a demonstration of house-to-house fighting. They fired live machine gun ammo down the middle of the street of a Hollywood-type simulated town while the riflemen raced from house to house, throwing live grenades through windows and dashing through the front doors to fire rifles at whoever might still be alive. One rifleman stepped too close to the middle of the street and took a machine gun bullet in the leg. The whole demonstration was immediately stopped. A medic from their unit raced to the wounded man. So did I, and for the first time I saw how to treat a bullet wound. The medic merely poured sulfanilamide powder onto the wound and tied on a small Carlisle bandage. An Ambulance took the wounded man away.” (Medic! How I fought World War II with morphine, sulfa and iodine swabs – Robert “Doc Joe” Franklin page 3)

This point is further stressed in the book Infantry Combat Medics in Europe, 1944-45 by Tracy Shilcutt.

“Enlisted men trained for an envisioned environment of stability and sterility as the Army introduced them almost casually to the basic concepts of first aid. In training, routine health care activities superseded field maneuvers as they inoculated their fellows, bound up sprained ankles, and dispensed aspirin. In addition, the Army’s pragmatic conception of soldiers who could perform medical tasks anywhere within the evacuation system meant that those enlisted men bound for the ETO front lines rarely understood their combat role due to their limited training” (page 24).

Robert Del Toro comes to the same conclusion in his article: “Fighting a War without Rifles, Deconstructing the Image of the Unflappable Medic”.

Training

As Shilcutt points out in the quote above, the company aid men were often inadequately trained for the difficult tasks they had to perform and had received little or no training that adequately prepared them for the (front line) circumstances in which they had to work.

So what was the training of a surgical technician like?

You can read all about this in the book Medical Training in World War Two.

The following is a synopsis of the information in this book on the training of surgical technicians:

1.Basic training

All surgical technicians had completed their Basic Training. This training was either given at the various Medical Replacement Training Centers (MRTC), later renamed Armed Forces Replacement Training Centers (AFRTC), or within newly activated divisions. For more information on these Centers, you can click on this link.

The details of this training were written in the MTP (Mobilization Training Program) of the Medical Department. At the beginning of WW2, the training was based on MTP 8-1 (9 September 1940).

It featured two weeks of military basics and eleven weeks of technical and tactical training.

I have combined the pages dealing with the training received by the surgical technicians in their basic training based on MTP 8-1 in this document: Training Medical and Surgical Technicians – Instructor’s guide for The Medical Department Mobilization Program 8-1 Sept 1942.

In the course of the war, the MTP was changed several times. One of the changes was the total number of weeks of training. As the demands of war increased, the time allotted for training had to be reduced to meet these demands. In November 1941 the MTP 8-5 reduced the training to eleven weeks total. The MTP 8-5 of January 1942 reduced it to a mere eight weeks.

As the training capacity of the Medical Department increased, so did the basic training. By November 1942 it was back to eleven weeks and by August 1943 it was increased to seventeen weeks.

In the second phase of basic training, some enlisted men were selected to be trained as medical or surgical technicians during the second phase of basic training. When they finished this training they were regarded as “junior technicians”

“The program also authorized the centers to provide special training for junior medical and surgical technicians. Such technicians were to be trained to fill intermediate level of specialization between basic medical soldiers and the graduates of enlisted technicians schools. Soldiers trained through these programs were not considered eligible for a rating higher than fifth class.” (Medical Training in World War Two, page 192).

2.Enlisted Technicians Schools

Some of the men were selected during their basic training for further, more advanced technical training:

“Individuals qualified to be trained as technicians were selected at the end of the fourth, eighth, and 12th week of the cycle and sent to Medical Department special service schools or enlisted technician schools for 8 to 12 technical weeks of training” (Medical Training in World War Two, page 190).

This advanced training was done in the Medical Department Enlisted Technicians Schools.

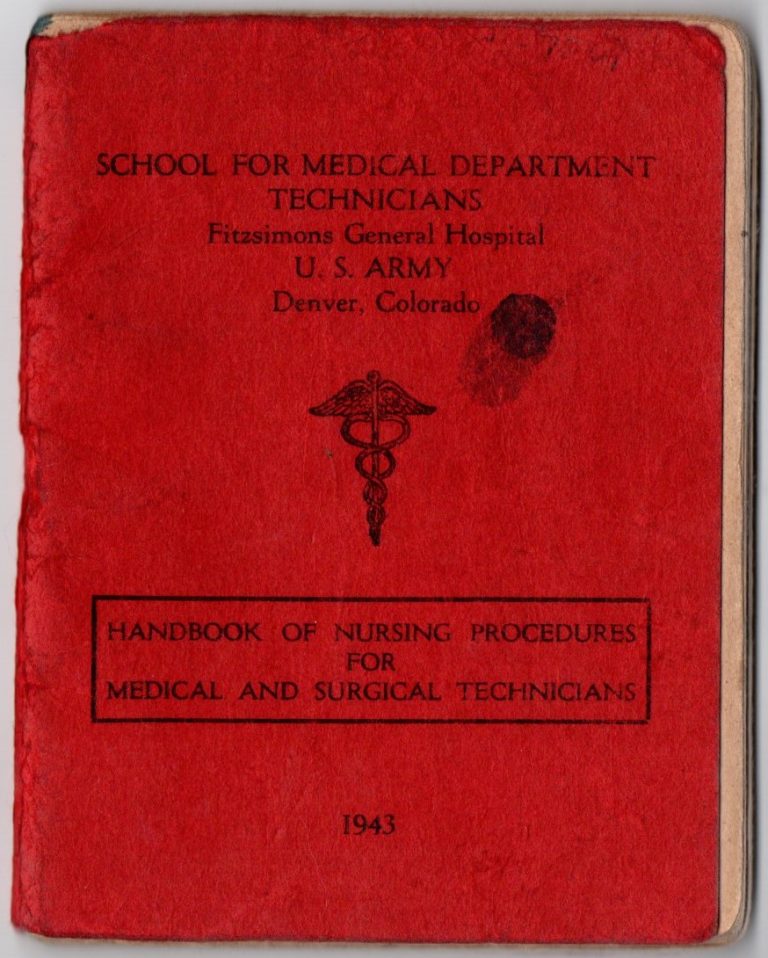

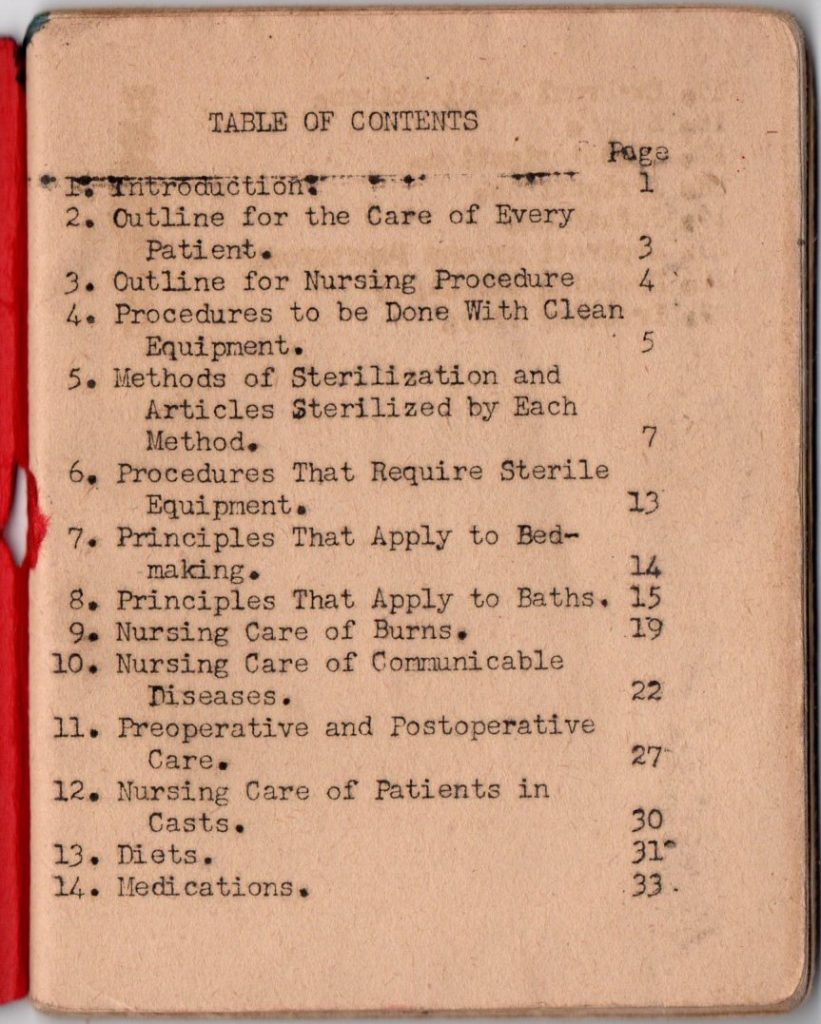

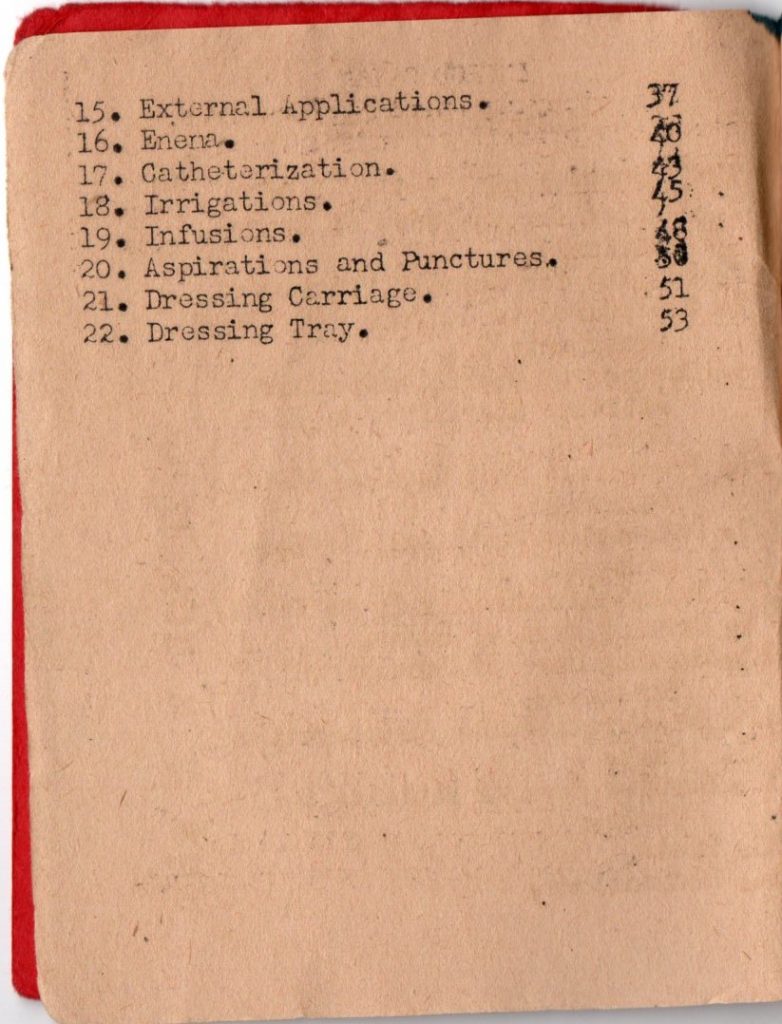

Often these schools were attached to General Hospitals. There were schools attached to Fitzsimons General Hospital and Lawson General Hospital for example.

The course for surgical technicians was two months initially. After August 1943 this was increased to three months. It was divided into two phases.

In the first phase, the trainees were given classroom training, (lectures and practical training).

This article published in the Bulletin of the U.S. Army Medical Department (No 80 – September 1944) gives us an idea of the sort of training that was given in the first phase.

The second phase consisted of working in a surgical ward in the General Hospital the school was attached to. The only difference between surgical and medical technicians was the ward the trainee worked in during the second phase: a surgical or a medical ward.

There was very little or no field training during these courses. After August 1943 this was changed: several hours were allotted to field training. “Each student was required to attend 4 to 8 hours of field sanitation, emergency medical treatment and individual security.” (Medical Training in World War Two, page 225).

“After August 1943, the program for medical and surgical technicians consisted of 12 weeks of intensive training designed to prepare soldiers for service at all types of medical units and installations.” (Medical Training in World War Two, page 226).

What is clear is that the Medical Department created this course to prepare its enlisted trainees to work in all sorts of medical units and installations under the supervision of physicians.

This training did not prepare them (enough) to work in the frontline units, with no supervision of a trained physician, being completely responsible for the lifesaving first emergency medical treatment given to casualties.

They were trained to be “a jack of all trades” when they needed to be trained as “a master of one”. The book Medical Training in World War Two summarizes this as follows:

“Medical Department soldiers of World War II came from all walks of life. Medical Replacement Training Centers, and those of other arms and services, applied the techniques of mass production to military training. In the image of the industrial process, centers took raw material from reception centers, forged a standardized product, and fed their output into medical units where the separate parts were finished and linked into the working whole. The accent was on economy, speed, uniformity, and volume production”. (Medical Training in World War Two, page 173).

- Unit training

For many surgical technicians who were sent to the ETO as replacements, their training ended here. I believe the “lucky” ones were the surgical technicians assigned to a unit well before it shipped overseas. They were able to get (some) unit training with the men they would serve with.

In this respect, many who served in the 4th AD were very lucky. The 4th AD was activated in April 1941 and first entered combat in July 1944. This meant that the division was able to train for a long time. Much longer than most divisions!

Even with a large number of personnel transferred to other units as a cadre, the 4th AD went into combat with a large percentage of well-trained units.

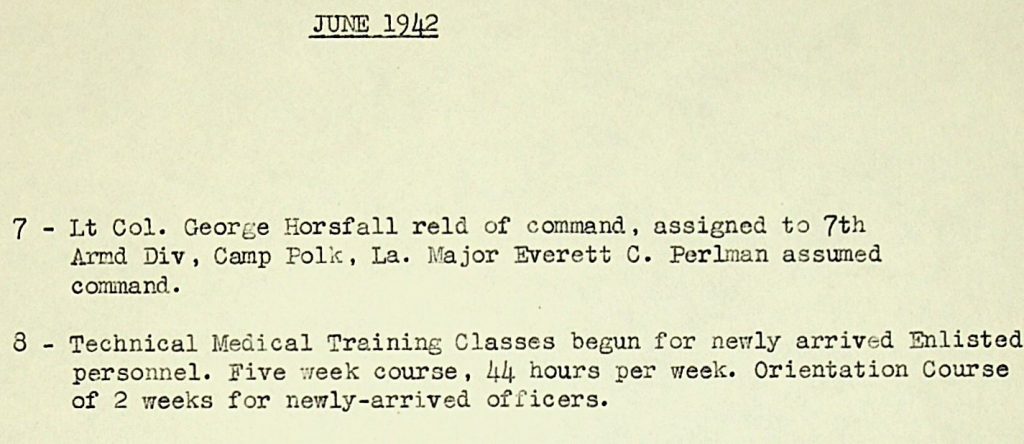

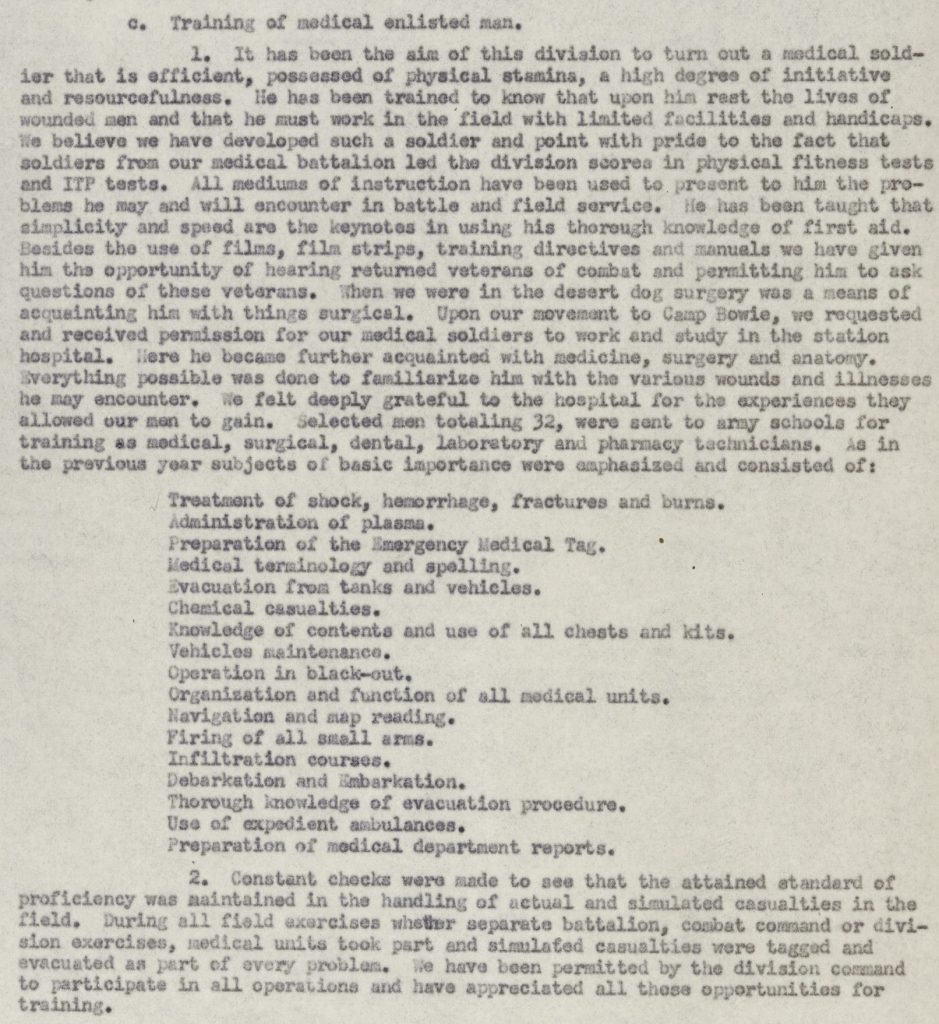

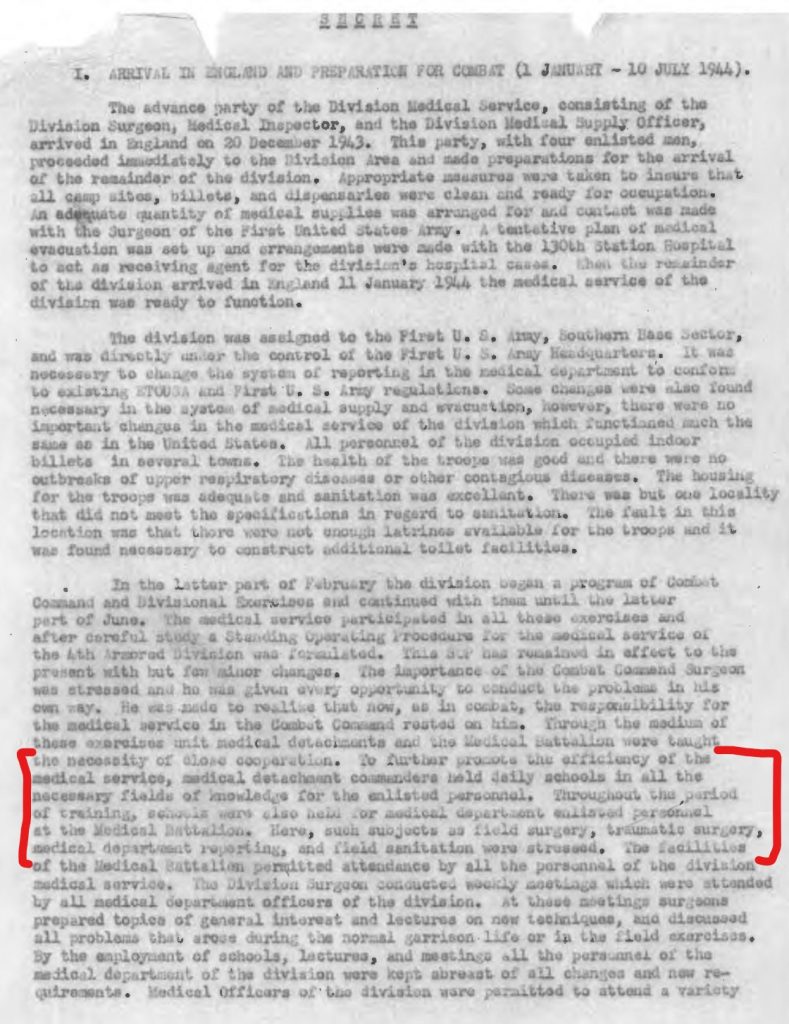

The following documents of the Division Surgeon and the 46th Medical Battalion, from 1942, 1943, and 1944, give us an idea of the Enlisted Personnel medical training in the division from its activation are shown here:

They give me the impression that within the 4th AD, a lot of effort was put into unit and technical training. I believe that by the time the division started combat operations its medical service was well trained. In the 4th AD, the problems with their company aid men started with their replacements.

4.Replacements

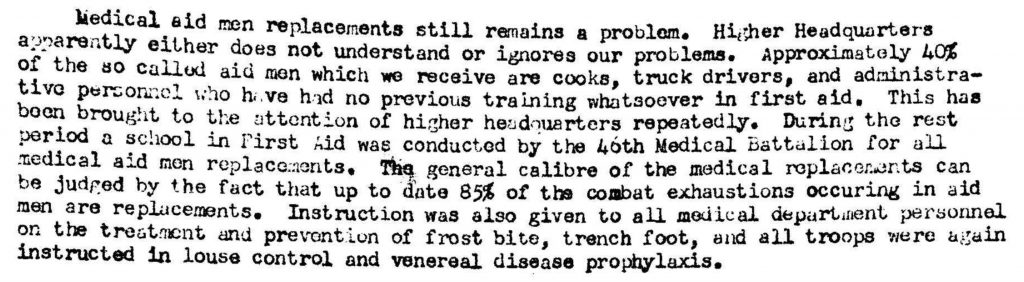

The US Army Medical Department trained a total of 43,587 surgical technicians in the Enlisted Technicians Schools during WW2 (I have not been able to find the total number of “Junior Technicians” trained during WW2). During the campaigns in Europe, this proved to be inadequate. Many more surgical technicians became casualties and needed to be replaced, than were available at the Replacement Depots.

In my research, I have found 70 surgical technicians (MOS 861) of the 4th AD reported as casualties (14 KIA/DOW; 25 WIA; 25 SLD (among these cases of combat exhaustion) and 6 MIA). As the documents I have found do not show all the changes in MOS or specify who was send to replace who, I can’t give you a definitive number of casualties among the company aid men of the 4th AD.

Some of the documents do specify some enlisted men as “attached to Company…” for a certain period. It is very interesting to note that often these men were not surgical technicians. My research shows many examples of litter bearers (MOS 657) and medical technicians (MOS 409) as “attached to Company..”.

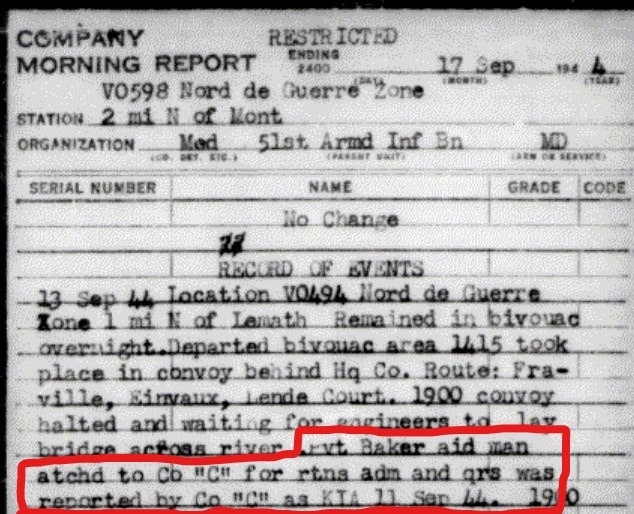

Look for instance on the unit page of the medical detachment of the 51st Armored Infantry Battalion. You can find Tec5 Harry E. Brigham (MOS 409: medical technician) attached to Company B, 51st AIB from 22 September to 9 October 1944. Or look at Pvt. Cecil A. Beadle (MOS 855: dental technician) and Pvt. Donald J. Baker (MOS 657: litter bearer) attached to Company C, 51st AIB.

Pvt Donald J. Baker (MOS 657) was killed in action on September 11th, 1944 while serving as company aid man in Company C, 51st Armored Infantry Battalion:

These examples suggest to me that the 4th AD often had to send men, who were not trained as surgical technicians, to replace company aid men simply because the right replacements were not available. Some of these men did not even receive the “jack of all trades” training of the surgical technicians. So their training was inadequate to perform the duties of a company aid man.

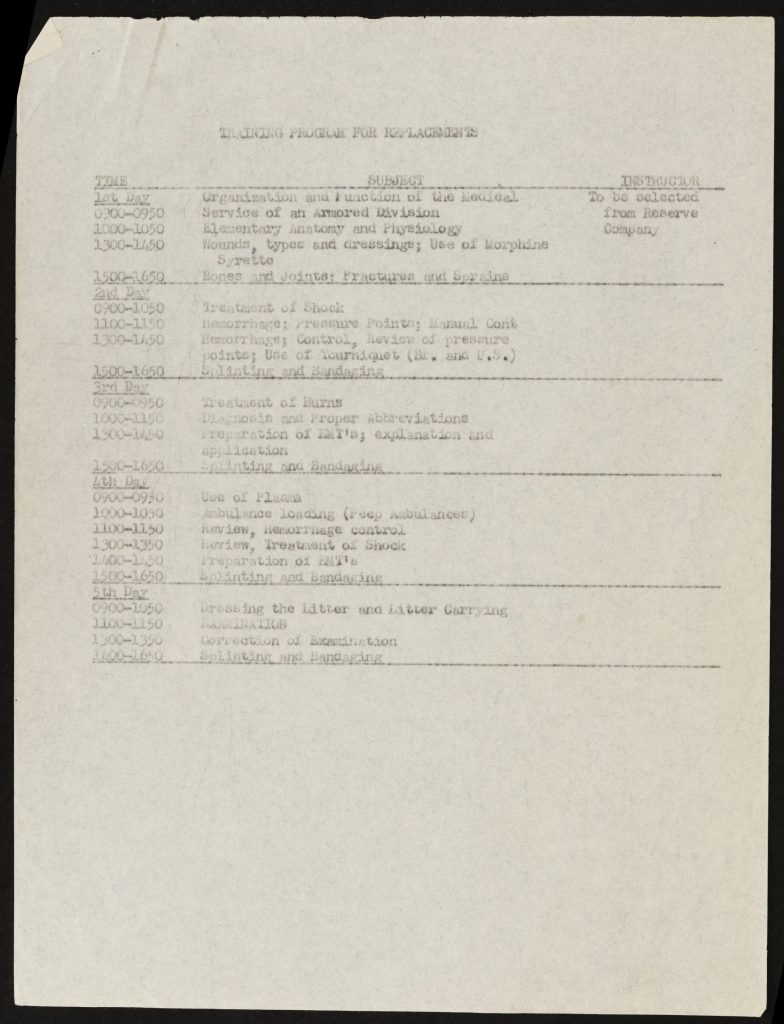

I have found the document that shows us the training program the Division Surgeon implemented for the medical replacement the 4th AD received. In this 5-day crash course the division tried to remedy the lack of their training.

Note the entry in the Division Surgeon’s Journal in October 1944. It really shows us the severity of the problem the 4th AD had with its medical replacements:

It is no surprise that in the 4th AD, these replacement company aid men represented a high percentage among the many combat exhaustion cases. In fact of all the casualties among medical personnel of the 4th AD (my research shows 383 cases in total), 154 are classified as SLD (Sick, in Line of Duty ~among these are the combat exhaustion cases).

I can’t begin to imagine the devastating feeling of hopeless inadequacy these men must have felt. Being confronted with casualties whose lives were in their hands, without the benefit of adequate training to prepare you for it.

Equipment

If their training did not prepare them enough for the duties they had to perform, were they at least supplied with enough equipment to do their duties?

To answer this question we need to take a look at the different standard medical kits for medical personnel. This link is an article on this subject. I found it on the great website of the WW2 US Medical Research Center.

According to the TO&Es in US Armored Divisions 1943-1945 the surgical technicians in an armored division started the campaigns in Europe with a medical kit, private. By the end of 1944, they were “upgraded” to a medical kit, NCO.

As we can see most of their equipment was various sorts of dressings/ bandages. With the “upgrade,” the company aid men became equipped with pain medication (both Aspirin and Morphine). This was the only significant difference between the various First Aid kits and the Medical Kits as far as I can see.

As Robert “Doc Joe” Franklin wrote:

“For the next two years, I poured sulfa powder and bandaged wounds. The wounds were penetrating, perforating, and lacerating: the bullets or shell fragments went in and stayed in, they went in and out, and they sliced through. Broken arms were splinted with bayonets and their scabbards. Broken legs were splinted with rifles. Controlling bleeding was imperative, and tourniquets might be required. Sometimes a wound would bleed a lot, and sometimes there was little or no bleeding – especially wounds from artillery shell fragments. When the shells explode they are white-hot, and they cauterize as they cut. (I’ve seen amputations with no blood whatever.)

You might say I learned my job as a medic through on-the-job training. Sometimes far away from the aid station, I had to make judgment calls and take risks with my patients. I am not a doctor. I think my greatest value was psychological. The men appreciated my being there to take care of them and see that they were evacuated.” (Medic! How I fought World War II with morphine, sulfa and iodine swabs – Page 4)

In many of the (auto)biographies I have read of men who have served as company aid men, they describe that they had other medication on them, like cough medicine for example.

As Richard Sanner, a company aid man in the 44th Infantry Division wrote in his book Combat Medic Memoires, Personal World War II Writing and Pictures: “As a medical aidman on the front line, I always carried in my medical bags an ample supply of ETH with C (elixir of terpin hydrate with codeine), a very good cough suppressant. Coughing on the front line was dangerous as the enemy could find you more easily. (Page 191)

I can certainly understand the added value of supplying the company aid men with these different medicines. They must have been provided to them by the personnel of the Battalion Aid Stations. I have not found any (official) document that describes this practice, however. Other means of supply might have been to “borrow” them from German casualties or POWs. Again, I have not found any documentation on this specifically.

With little more medical equipment available than in the First Aid kits, the company aid men had to improvise and innovate a lot to provide often lifesaving treatment. There are many examples of this. I will quote Shilcutt’s book to give you some examples here:

“Although basic military medical training hammered fundamental techniques for controlling bleeding, managing pain and minimizing shock, the implacable reality of combat forced aid men to improvise lifesaving techniques and nowhere is this better illustrated than in medics’ approach to devastating chest wounds. A direct bullet strike sometimes caused chest trauma, but more often the shrapnel from exploding shells tore into the chest cavity, compromising the wounded man’s breathing. The wounded man might inhale, but air entering the chest cavity through the wound would not allow the lungs to expand. For such chest wounds, the aid man first had to seal the damaged area. This, according to stateside instruction could be done by covering the sucking wound first with a regular bandage and then with a patch torn from a raincoat.

This technique could work, but the aid man might not have a raincoat, or the advised protocol might fail to decompress the lung. In such cases, medics experimented with innovative remedies. One aid man used an intact raincoat as a large binding around the wounded soldier’s entire body to create an effective seal; another used mechanic’s engine tape, finding that it tightly adhered bandages to the skin. One replacement aid men, bereft of any medical training, simply laid the handiest heavy object, such as a rock, over the wound to seal the damaged lung area. Not prescribed in any medical manual, and often not in keeping with the sterile protocol, such rough and ready treatments did save soldiers’ lives.

While in some cases combat medics had to invent new procedures, in other instances they discovered that army-issued medical equipment was woefully inadequate. In Italy, Private Russel Redfern of the 88th Division found that the free-bleeding arterial wounds presented him with the greatest challenges of his job. He learned that government issue (GI) uniform belts made far better tourniquets than those in his medical kit. In addition, on more than one desperate occasion Doc Redfern simply thrust his finger inside wounds to restrict the flow from the arteries until a shoelace or other handy substitute could be located to tie off the hemorrhaging vessels”(page 52-53).

I believe we can conclude that the company aid men had little more equipment at hand than the soldiers had in their First Aid kits. The most significant difference was brought by the “upgrade” to Medical Kit, NCO which at least provided the company aid men with morphine and Aspirin to reduce pain. Anything else they might have needed they had to get by improvisation and innovation.

Medical Detachment vs Combat Unit

As I wrote in the introduction, the company aid man was a part of the medical detachment of a battalion from an administrative point of view. They were assigned to serve in a company or platoon by the battalion surgeon who was his commanding officer.

While serving in a combat unit this command structure did not change officially. Naturally, the company aid man was influenced by the orders of the commanding officer of the unit he served in.

This somewhat ambiguous role could be helpful and a hindrance. Some found that it gave them a level of independence. Company aid man Richard Sanner wrote of his time right after VE-day: “as a medical aidman, I had no regular assigned duties in the infantry outfit to which I was attached: KP, guard duty, policing the area, drilling, formations and inspections, for example. My time was quite flexible, with no need to obtain permission from anyone if I wanted to go someplace”. (Page 141-142)

Some company aid men found that their separate status in the combat unit had some other positive influence as well. The men in the unit often ended up talking to the company aid man as they would do to a chaplain. Richard Sanner wrote in a letter dated 21 March 1945: “As an aid man, as Ray knows, I am the medical aid person for the men on the front line. We treat all casualties, illnesses’, injuries, sickness, and also act as chaplain. I say this latter, not because we really are, but because the men come to us with many troubles. I guess we are the ones to talk them over with.”

Others found that not being an integral part of the combat unit left them somewhat detached from the unit’s comradery. This was even more so for replacements. We know that combat replacements often felt like orphans when they were first assigned to their new units. Only after some combat operations did they start to feel that they were accepted as part of the team. For the replacement company aid man, this role as “part of the team” was often never fully realized.

Even when they were not an integrated part of the combat unit, company aid men were often highly respected by the men they served with. There are many examples of this respect. Company aid men have told stories of how the men would dig a foxhole for them, how they would be ushered to the front of the line when the kitchen trucks prepared hot food etc.

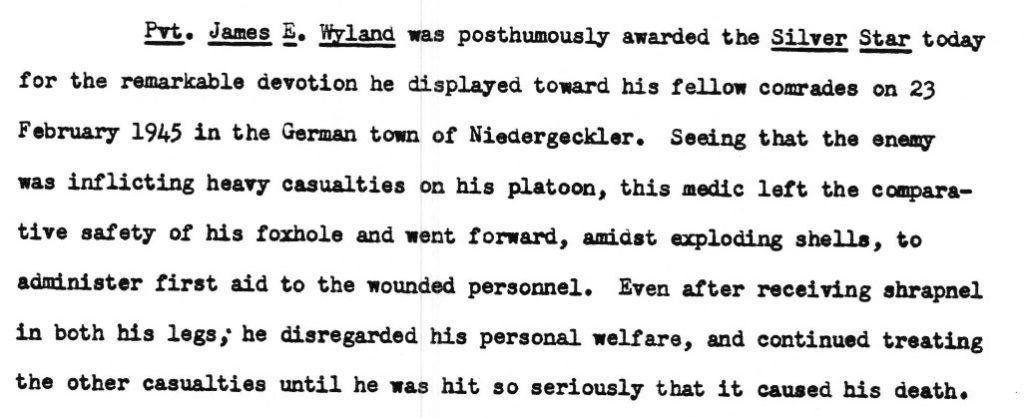

When we look at the 10th Armored Infantry Battalion’s Diary for May 1945, we find several medals being awarded to some of the company aid men. I will show only two of these here, but when we read them we can certainly understand the enormous respect the men had for “their medics”.

Now that we are talking about medals, we find one other significant distinction existed between the company aid men and the men they served (with) in the combat unit: they were not eligible to receive the Combat Infantry Badge. The company aid men also did not receive combat pay as the combat soldiers did. Many of the combat soldiers felt that this was an injustice to the company aid men.

It is reported that in some units the men all donated some of their money to rectify this.

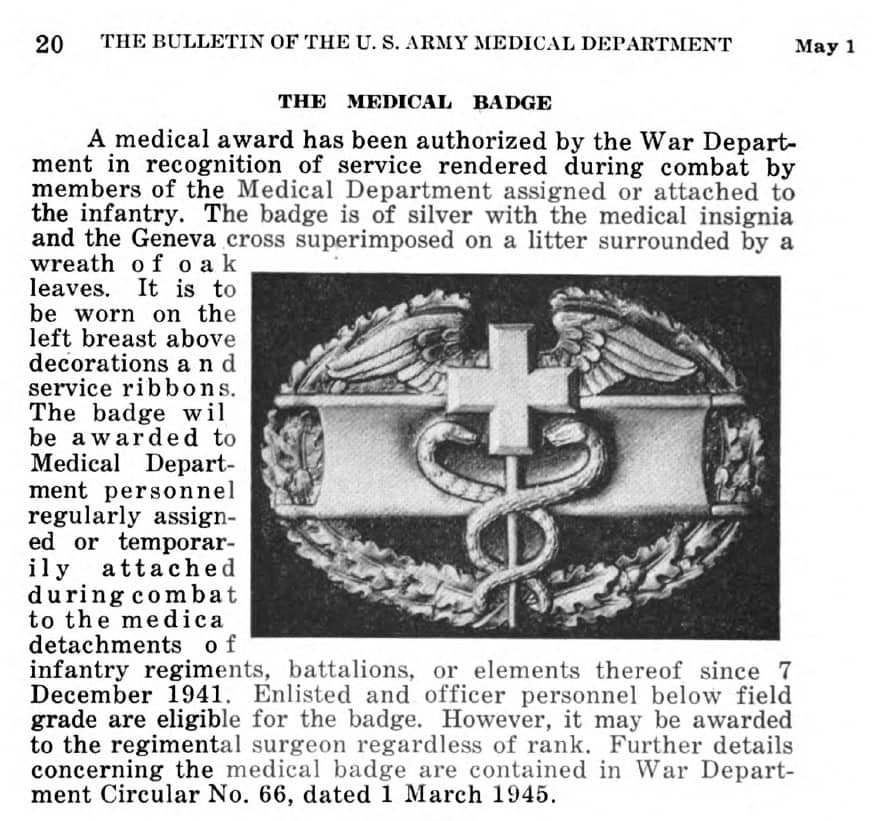

The War Department finally came up with a (partly) solution to this discrepancy: the Combat Medical Badge.

Richard Sanner wrote in a letter dated April 10, 1945:

“We are to get our medic badge soon, I hear. Maybe next week. I also hear that a new bill; the old one was not accepted by the War Department; to give combat medics $10 extra pay per month. Everyone here, especially the infantrymen, think the medics should get the pay. I hope it, the bill, goes through OK”

It didn’t. The men did receive the badge, but not the pay. At least not until August 1945:

General Board 1945

After the war, a General Board, United States Forces European Theater was convened to find and discuss the lessons of the campaigns in Europe. One subject was the evacuation of human casualties.

In the report, there are some lessons about the company aid men. I have included the part on the company aid men in the infantry. However, the General Board stated that the conclusions are equally relevant to the company aid men in the armored forces.

Another report was on the “training status of Medical Units and Medical Department personnel“. I have included the relevant conclusions here:

Conclusion

As Division Surgeon, Lt. Col. Abrams predicted in this document on reports and regulations (dated June 26th, 1944): the aid men did not disappoint and they often were very courageous.

With often inadequate training and with a minimum of medical equipment the company aid men that were attached to combat units by their battalion surgeon, had some of the most difficult duties in WW2.

Through mostly improvisation and innovation they performed lifesaving treatment of casualties earning the highest respect by the men they served with.

Pingback: Medical Evacuation and Treatment Series. Part 3: First echelon evacuation. - Patton's Best Medics

Pingback: Medical Evacuation and Treatment Series. Part 4: Battalion Aid Station. - Patton's Best Medics

Pingback: Silence - Patton's Best Medics

Pingback: Medical Evacuation and Treatment Series. Part 5: Medical Battalion. - Patton's Best Medics

To be sure with your thoughts here and I like your website! I’ve bookmarked it so that I will go back & read more sometime soon.

Wow, this is very fun to read. Have you ever considered submitting articles to magazines?

Thank you! And no, I have not thought about publishing articles in magazines (yet). I am considering writing a book on the medics of the 4th Armored Division in the future. But for now, I just enjoy writing these blogs. They also help me researching a separate piece of the entire story, so I can fully understand that particular part. If you have any suggestions for future topics, please let me know. I am working on a blog about the medics who became POW. And a blog on trench foot/ frostbite is on my list also. Reinier

Just thought I would comment and say awesome theme, did you create it for yourself? It looks excellent!

Thank you for your comment. And yes, I did create the entire site myself. Reinier

Hello I think your blog is very good i found it on google I think will come back again

Thank you. I would love for you to return and read some more. Reinier

Enjoyed examining this, very good stuff, thankyou . “What the United States does best is to understand itself. What it does worst is understand others.†by Carlos Fuentes.

Thank you for your comment. I am glad that you enjoy this. Reinier

Thank you for the interesting read. My Dad was a medic, serving in North Africa, Sicily, Italy. He was also involved in the Battle of Anzio. A very non-assuming man who didn’t want to talk about his experiences. He was a brave one, earning the silver star and bronze star. He was offered the Purple Heart, which he declined, stating that more brave men than he deserved it.