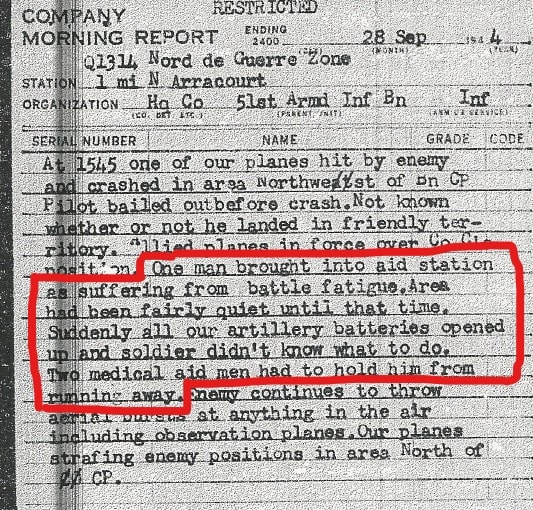

This Morning Report describes one soldier suffering from “battle fatigue” and the efforts of the aid men to help him. But what is “battle fatigue” exactly? What were the symptoms and signs? And how was it treated?

In this article, I will explore these questions and answer them first for the US Army in general and then for the 4th Armored Division specifically.

Definition

First, it is important to note that many different names were used during the War to describe the same problem:

Combat exhaustion, battle fatigue, and war neurosis to name a few. For clarity, I will use the term combat exhaustion.

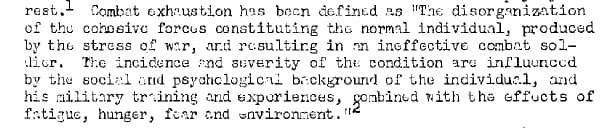

It is very hard to find an exact definition for combat exhaustion. There is one definition used in the 1945 General Board on combat exhaustion:

The “disorganization of the cohesive forces” was shown through many different symptoms: anxiety, panic/ hysteria, apathy, depression, inability to sleep, etc.

The term “exhaustion” or “fatigue” was chosen as a diagnosis in April 1943 as a result of the process the US Army went through to relearn the lessons of World War I. At the beginning of World War Two, the Army had forgotten or dismissed these lessons. It was believed that by careful selection of men entering the Army, it would be possible to “eliminate all individuals predisposed to neurotic reactions” from entering the Army, thereby preventing the reoccurrence of what was called “Shell Shock” during WWI.

During the campaign in North-Africa, a large number of men were evacuated for “neuropsychiatric diseases” to hospitals in the rear. It was found that treating these men in the rear was difficult. Their symptoms became chronic and only a small percentage was able to return to the front.

As the preservation of fighting strength is one of the main goals of the US Army Medical Department, something had to be done to improve the situation.

First, a reevaluation of normal and abnormal reactions to combat had to be made. It was deemed normal to be afraid and stressed during combat, so all the signs of this fear: anxiety, tremors, headaches, nausea, etc. were no longer a reason for evacuation. Only soldiers who were unable to function anymore were to be evacuated and treated.

One of the most important lessons learned was that the percentage of men able to return to duty from treatment increased dramatically when they were treated as far forward as possible, preferably within the division. It was believed that this was partly so effective because the men were treated within the “sound of the guns”, never truly leaving the combat area and staying close to their duty station. This kept them from changing their behavior from soldier to patient too much.

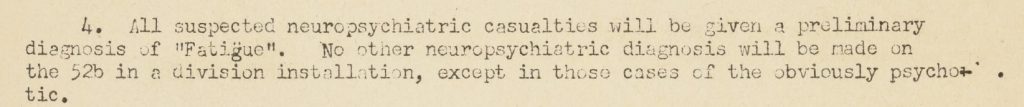

Also, the emphasis was placed in the communication to the soldiers on the physical nature of their symptoms, not the psychological. This is why the term used on medical tags and records was “exhaustion”. Any soldier who would read the diagnosis on his tag would see that “all he needed was some rest”. This remained the term used throughout the War, as we can see in the 4th Armored Division’s Surgeon memo on Reports and Regulations, dated 26 June 1944:

One other result of this process was the addition of a Division Neuropsychiatrist to all combat divisions. He was responsible for the prevention and treatment of combat exhaustion within the division.

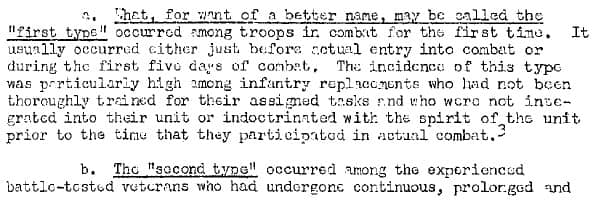

The General Board on combat exhaustion found two “types” of combat exhaustion:

Soldiers experiencing the first type of combat exhaustion showed predominantly signs of anxiety. It was believed that this type was mostly preventable by training the men well, by good leadership, and by high morale in the unit. Many of the men treated for the first type were able to be returned to duty. This type was most commonly seen with newly arrived, inexperienced soldiers.

The second type, occurring in experienced soldiers, was sometimes called “Old sergeant’s syndrome”. Soldiers experiencing this type showed mostly signs of apathy and depression. They were reluctant to be evacuated and often felt guilty after they were evacuated for treatment. It became clear that the only effective way to prevent this type of combat exhaustion was regular periods of rest. Unfortunately, these periods of rest were few and far between in the ETO as there were simply not enough divisions and replacements available.

Many reports found that “Old sergeant’s syndrome” became endemic after about 120 days of combat.

We can see this in the chapter on the Third Army in the book Neuropsychiatry in WW2 overseas theaters, page 325- 366:

Men suffering from “Old sergeant’s syndrome” were often not able to return to their former duty, even after treatment. Many of these men that were returned to duty were send back within a short while. Their officers found that they were simply unable to function back on the frontline.

It was discovered that these men functioned well in a new duty in the rear area of the division. This way they could still contribute to “their unit”, which helped to alleviate their feeling of guilt. They were often reassigned to units in the Division Trains in the 4th Armored Division.

Treatment

With the relearning of the lessons of WWI, the focus of the treatment of combat exhaustion cases was to:

- Treat the soldier as far forward as possible. Preferably at the battalion aid station, or when necessary at (one of) the division clearing station(s). Soldiers would only be evacuated to the third echelon of the evacuation chain when they were unable to return to duty after treatment.

- Treat the soldier and return him to duty as quickly as possible. Most soldiers would be treated at the battalion aid station for a few hours to a day. At the clearing station, treatment would be for two or three days.

- The main method of treatment was rest, assisted by sedation when necessary.

One of the medicines used for this purpose was Sodium Amytal. It came in blue capsules. It was so effective in “knocking a man out” that its nickname became “Blue 88” (a reference to the German, dual-purpose 88 mm. gun).

A sedated soldier was difficult to transport when a unit needed to move. So this treatment was often reserved for the clearing stations. At the battalion aid station, a light dose of a sedative was used, just to help a soldier relax a bit.

After rest/ sedation, the soldier would be interviewed by the Division Neuropsychiatrist for a few minutes to see if he could be returned to duty. Some men were kept for a few extra days. These days were used to return the soldier to a soldier’s routine. The thought of this was that when you make him act as a soldier rather than a patient, it would accelerate his return to duty. He was given a new uniform and he was expected to take part in training exercises.

For a more elaborate description, see the chapter in the Manual of Therapy ETO: page 129-136.

When treatment did not fully restore a soldier’s ability to return to duty, but it was felt that this was still a realistic possibility, a soldier would be assigned to a supporting unit within the division. Here he would be monitored to see if he recuperated (measured by his ability to resist the sound of artillery fire) or if he should be evacuated in the end.

We see this in the AAR of the 4th AD Division Trains:

Totals

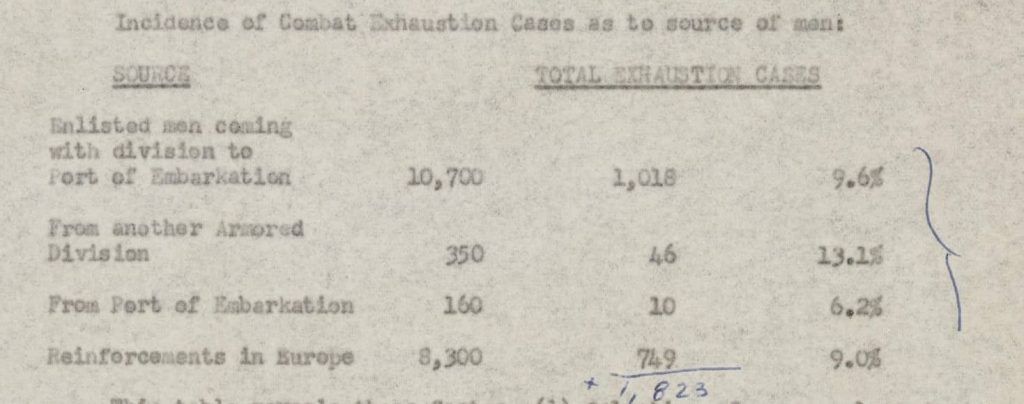

According to the book Medical Statistics in World War Two, a total of 929,307 soldiers were admitted for neuropsychiatric diseases. Of these, 648,460 cases were for psychoneuroses (of which combat exhaustion was the biggest part).

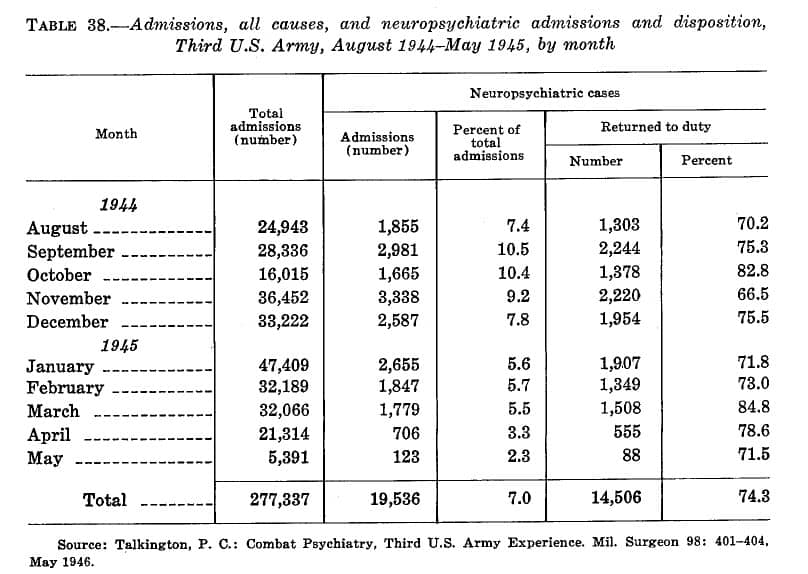

In the ETO, this number was 160,924 (the General Board, in 1945 stated this number as 102,989). Of these 19,536 cases were within the Third Army. Almost 75% of these cases were returned to duty, at least for a little while.

Neuropsychiatry in WW2 Overseas, Third Army:

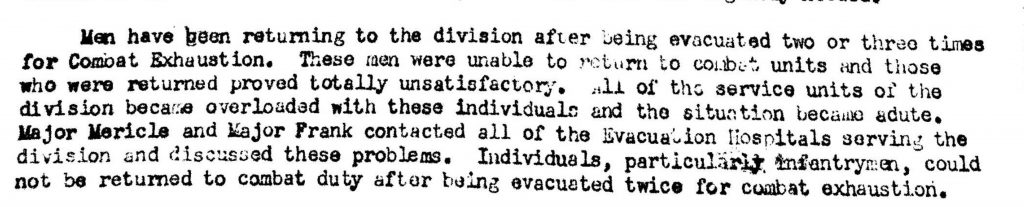

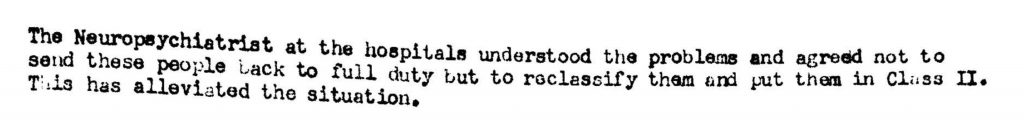

Of the soldiers who returned to duty, after evacuation and treatment in an Evacuation Hospital, many were unable to function properly at the front. This was especially true for the soldiers, who had been treated for combat exhaustion before.

Within the 4th Armored Division, this created a problem:

Combat exhaustion in the 4th Armored Division

For a closer look at this topic within the 4th Armored Division, let us follow the Division Neuropsychiatrist, Major Earl Mericle.

For more information on this topic, I have included all the articles he has written on his service in the 4th Armored Division here:

Mericle articles:

Psychiatric situation paralleling tactical situation in the Fourth Armored Division

He joined the division on 25 November 1943. The division was finishing its training at Camp Bowie, Texas and it was alerted for overseas movement around this time.

Major Mericle found that due to the previous selections made by the reorganization into a “light” armored division and the creation of cadres for newly activated divisions, many of the “unfit” had already left the division.

The news of the move overseas and the transfer to England did cause some “anxiety reaction” in several soldiers.

At the Port of Embarkation 150 reinforcements were assigned to the 4th Armored Division. The Division G-1 and Major Mericle interviewed about 300 men (each about a minute) to select the best 150 men, hoping this selection would prevent future problems with these reinforcements.

England

In England, the training continued. Mericle described this as “training towards an aggressive attitude”. He spent much time with the line officers discussing “the importance of leadership and aggressive attitude”. He also spoke to them about the symptoms and believed causes of combat exhaustion.

He invested much time in his working relationships with the Division Surgeon (under whose authority he worked), the G-1 and AG of the division (as personnel officers), the chaplains, and the special service officer (whose duty contributed to the morale of the division), and the JAG (as many of the cases on the JAG’s desk needed Major Mericle’s opinion).

During the stay in England, 176 men were evacuated for neuropsychiatric reasons. Many were found to be of “inadequate personality”. Some of them were replacements from other divisions. Mericle describes them as “cast-offs”. The actions of Major Mericle correspond with the belief that combat exhaustion could be (partly) prevented by a thorough selection.

After D-Day, some patients with anxiety reactions came in for treatment, whereas before D-Day none had been seen. The anticipation of going to France for combat sparked these reactions.

France

After the arrival of the division in France, it spent some time in an assembly area. Here, after reading articles on mines and snipers, the men were found to be somewhat “trigger happy” and displaying an “overemphasis on digging-in”. Mericle feared that this would decrease their aggressive attitude.

On July 17th 1944, some of the armored infantry units went into the frontline. A common tactic used by the Germans was to send out nightly attacks in sectors where green allies units held the line. This was also done against the armored infantry units of the 4th Armored Division. As Mericle wrote: “Early the next morning, the first combat exhaustion cases came in”. These men were convinced that their battalion had been wiped out. This first experience with combat is similar to the “first type” of combat exhaustion. What aggravated the situation was that the armored infantrymen fought as “regular infantry”, rather than armored infantry. They were dismounted and without the support of the tanks, they had trained with.

The Germans used this tactic three times against the 4th Armored Division’s infantrymen. Each resulted on average in 18 exhaustion cases coming in for treatment. Mericle described their symptoms as mostly “anxiety type reactions, but there were several who had Parkinson-like reactions”.

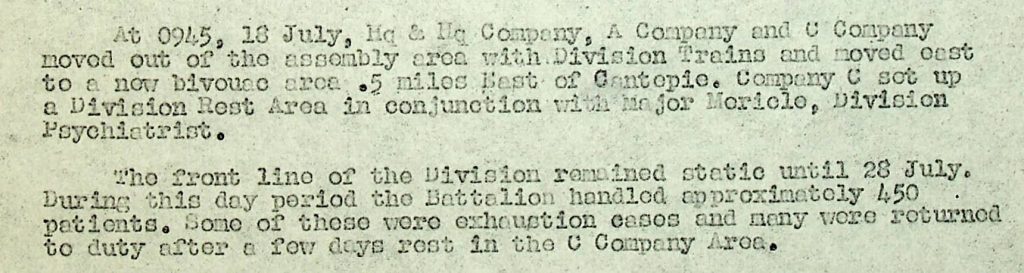

It is at this time that the reserve medical company established a “division rest center”/ auxiliary treatment center.

46th AMB AAR:

Division Surgeon Journal:

Throughout the War, such an auxiliary treatment center was continued at the reserve medical company (mostly Company C, 46th Armored Medical Battalion).

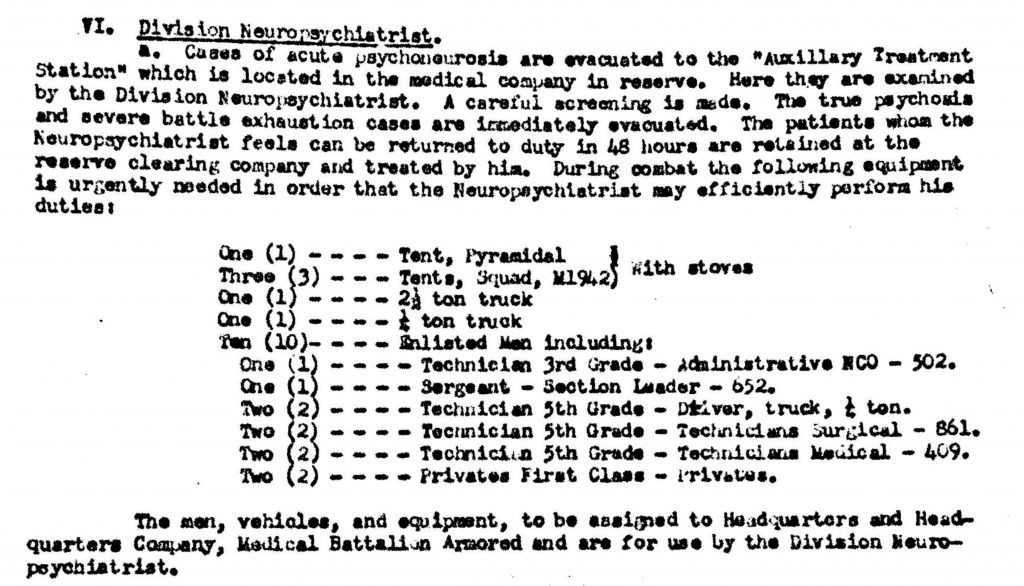

One of the major problems was that the division neuropsychiatrists brought no additional personnel or equipment to the TO&E of the medical battalion. Major Mericle tried to arrange for additional personnel, tents, rations, and transportation to be more effective.

He wanted to give his patients one and one-half rations because they had all lost weight. He also wanted to provide them with shaving equipment and fresh uniforms. Whenever possible, he would send them to get a hot shower. All these parts of the treatment helped the men get better sooner. On September 12, 1944, he was assigned Pvt. Douglas Smith as his driver. This made it possible for him to visit the battalion surgeons and assist them when necessary.

As far as I can tell, he never received the additional tents and personnel needed to man the treatment center. He was dependent for this on the reserve medical company.

A proposal for a change in the TO&E was written by the Division Surgeon, which included all the necessary items for a properly equiped auxiliary treatment center:

Breakthrough

Due to the highly successful offensive, starting with the breakthrough by Operation Cobra, the number of combat exhaustion cases decreased markedly. In the next 55 days of continuous combat, “only” 156 men were admitted for combat exhaustion. Of these, 70 were returned to duty.

Mericle describes that the success of the offensive and the fact that the men were fighting in the way they were trained (mobile mechanized warfare) both contributed to the relatively low number of cases. It is interesting to note that pure physical fatigue, which still plagued the men during this period of non-stop fighting, did not by itself cause high numbers of combat exhaustion. He noted that this fatigue showed itself by increased startle reactions and tension shown by almost everybody. Also, a marked increase in alcohol consumption was noted (which was plenty available in France).

But morale was excellent. The troops were proud of their accomplishments. These factors seemed to provide them with some protection for combat exhaustion.

Gasoline shortage

In early September the Third Army was stalled due to the overextended supply lines. This gave the Germans just enough time to organize a defense and even start a counteroffensive (the Battle of Arracourt. Also, the weather started to deteriorate. The highly mobile type of warfare that the 4th Armored Division excelled in had come to an end.

All these factors contributed to the marked rise in combat exhaustion cases, that started September 16th, 1944. It reached alarming numbers on September 27th, 1944. On that day alone, 71 men were admitted for combat exhaustion. Of these 55 came from the 10th and 51st Armored Infantry Battalions. Between September 15th and September 30th, 1944 a total of 355 incidences of combat exhaustion were recorded.

Major Mericle described this as follows:

“At this time some of the best men in the division became exhaustion casualties. There was a high percentage of non-commissioned officers of the first three grades.”

In a letter to the Division Surgeon, Lt. Col. Morris Abrams, he wrote: “Men have been in combat for ten weeks, which is evidently the breaking point for many men”

What we see here is the beginning of the “second type” of combat exhaustion: “the Old Sergeant’s Syndrome”.

“Our medical clerk, Corporal Morelli, developed a case of combat fatigue right under my nose. We got caught in a surprise artillery attack. We had no time to seek foxholes. Morelli and I dove under the medical trailer. As the shells landed and burst, a fragment hit the tire just above my head. There was this loud hissing sound. Morelli shouted into my ear, “Captain, I’m hit! I’ve been shot!” I yelled back, “Bleep-bleep it Morelli! You’re not hit! That’s just the bleeping tire going down!” But Morelli had had it, and he was no good from then on. We evacuated him. He never came back. He was assigned as a clerk/typist to a unit in the rear. General Patton just didn’t understand that sort of thing. It just wasn’t in his character to appreciate the fact that we can’t all be perfect at all times.” To Hell With the Germans! Drive on, Garrison!-Dr. Richard R. Buchanan, M.D., Battalion Surgeon 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

Rest

Early October the division was pulled off the line (except for the artillery units). Even though the weather remained terrible, the rest improved morale quickly.

Mericle noted in one of his article’s:

“A visit by the commanding general does more good than a day’s treatment”.

This effect was also noticed by Albin Irzyk (then battalion commander of the 8th Tank Battalion). In his book, He rode up front for Patton, he described the effect of a short visit to the battalion by General Patton:

“As it reached Al, the jeep screeched loudly again—this time as it came to sharp, abrupt stop. Al saluted smartly. Behind him, three huge farm horses who had been drinking at a trough, backed away, turned, and began lumbering up the street, apparently startled by the noisy arrival. With a wide, crooked grin, exposing bad-looking teeth, General Patton returned Al’s salute, and announced loudly, “Ha, ha! I see that I’ve started a cavalry charge.”

With that he hopped out of his jeep, and moved briskly up the street with Al in tow and about a half-step behind. He stopped at every vehicle, at every cluster of soldiers and had something to say to each—a question; a word of encouragement or appreciation; a compliment; a wisecrack; a good-natured dig. In an instant, he had established total and complete rapport with these men; they were literally eating it up. He was a master at it. His stops were brief, and he kept moving. But in thirty minutes or so, he had touched virtually every man in that battalion. Those who were located in the back buildings or side streets had darted up for a peek. His jeep had slowly followed him up to the far end of the street. Now he had it turned around. He slapped Al on the shoulder and exclaimed loudly, “Keep up the great work!” With that, he hopped up onto his jeep, grabbed the windshield, again, and as the jeep started moving, returned Al’s salute. The vehicle quickly accelerated, and headed back in the direction from where it came, and at the same speed. He stood ramrod straight, clutching the windshield with one hand, waving to the troops on both sides with the other—perhaps unconsciously emulating and reenacting the triumphant roll-bys of the Roman conquerors, about whom he had read so much, and with whom he empathized. The troops, of course, stood rooted to the ground, transfixed, and bug-eyed. Then with another screeching ninety degree turn, he was gone.

Al was amazed at the tremendous impact that one man could have on a body of men. After his visit, troopers of the Eighth worked furiously all day, as if with renewed energy, almost like elves in the workshop, after being visited by Santa, who had vigorously nodded his approbation. The men, as they worked, and as expected, talked about nothing else all day. As the days passed, the tales began to grow—some would eventually expand to legendary size, somewhat like the proverbial fish story.

The visit made the men almost ecstatic, There was no question that the army commander knew who they were, what they were doing and had achieved, and had indicated his appreciation and approval of their efforts. There is almost nothing in the world like recognition and pride, and they were handed a big dose of both this day.” (Page 228-229)

During October a total of 194 men were treated for combat exhaustion. 61 were returned to duty.

Lorraine Campaign

About November 8th 1944, the division was again on the offensive. This time the objective was the Saar Region on the German-French border. The weather remained extremely bad. The heavy rains made the terrains extremely muddy, forcing the units to fight on the roads. This situation made it relatively easy for the Germans to defend.

Also, many men were unable to change their wet clothes and it was difficult to get hot food to the frontline.

As we can imagine, all these factors lowered morale considerably. Around this time trench foot and frostbite cases started to show at the aid stations. Many reports indicate that with the rise of trench foot/ frostbite cases, combat exhaustion cases decreased. I have not been able to find any good reason for this. Perhaps these medical conditions appeared before the onset of combat exhaustion, causing the men to be evacuated before they presented themselves with combat exhaustion.

Mericle wrote:

Clearly, what he describes is “second type” combat exhaustion/ “Old Sergeant’s Syndrome”.

During this campaign, the Auxiliary Treatment Center was located in “a former French Officer’s barracks”. I have found the Company C, 46th AMB, the reserve medical company at the time, was located in Dieuze France. In Dieuze, there is a French Army “Caserne”. I believe the described officer’s barracks are the building in this postcard:

Calm before the storm

On December 10th, 1944, the 4th AD was again afforded some rest. The men were quartered in building to keep them warm and dry, which helped restore morale. Some were allowed passes to Nancy or even Paris.

The Battle of the Bulge

The 4th AD was alerted to move to the north on December 19th, 1944. On December 20th, the units of the division drove towards the area around Arlon, Belgium in icy cold weather.

Major Mericle noted that the cold did not affect the men as much as the wet, muddy conditions of the Lorraine Campaign. The frozen ground made it possible for mechanized units to maneuver off-road again.

From December 10th, 1944, to January 2nd `1945, a total of 246 combat exhaustion cases were encountered. 95 of them were returned to duty.

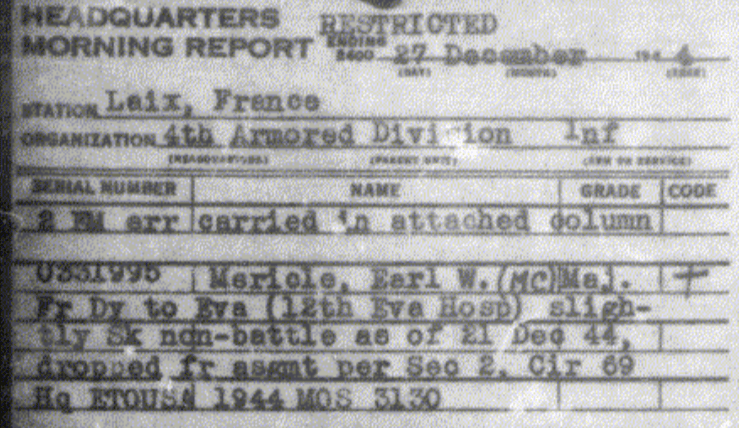

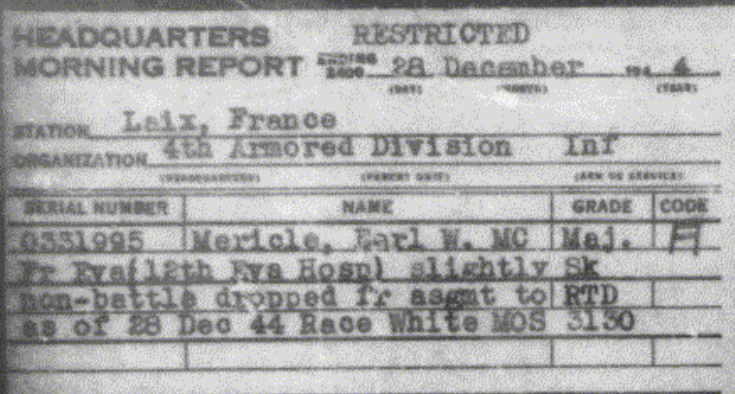

We should note that Major Mericle himself was evacuated for “SLD”(sick in the line of duty) on December 21st. He returned to duty after treatment at the 12th Evacuation Hospital, on the 28th December 1944. We have no way of knowing whether his sickness was combat exhaustion, or not.

I did find a description of Major Mericle’s condition, written by Captain Richard Buchanan, battalion surgeon for the 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion, attached to the 4th AD:

“I was sympathetic to men whose nerves got frayed. In spite of what General Patton wanted to believe, combat fatigue was very real. I’m not sure how many men we evacuated from the 704th because of it, but I know it was a sizable number. Most of the cases occurred early in the war when we were in France. I had occasion to go back to the Combat-Fatigue Treatment Center where a rest-sedation technique was being tried. This program had been developed by a former teacher of mine, a neuro-psychiatrist named Dr. Howard Fabing. The program consisted of three days of relatively deep sleep induced by healthy doses of Nembutal. After this period of withdrawal from reality the men were sent back to combat. While checking on the progress of some of our own men, I talked at length with the psychiatrist in charge. I was quite shocked to discover that he was nearly a combat-fatigue case himself because of the personal struggle he went through when he sent men back to the front, knowing their pleas not to be sent back to the line were justified. He was under orders to do so. He had tears in his eyes as we talked. I wondered how long he would last.”

To Hell With the Germans! Drive on, Garrison!-Dr. Richard R. Buchanan, M.D., Battalion Surgeon 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion (bolt lettering added by me for emphasis).

Whether or not Major Mericle “lasted”, it is clear how the enormous stress of his duty was weighing heavy on him.

Showing us some of the stress of his duty, Major Mericle wrote this is one of his articles:

“In treatment, the psychiatrist, whenever possible must still consider each patient as an individual. In this way it is possible to reintegrate the greatest number of men with their former duty. A few minutes spared to a patient may mean the difference between success and failure of treatment.” (bolt lettering added by me for emphasis).

In the same article, he described his “tactics” for returning the men to duty:

“Always ask the men to return to duty in the presence of others. In starting to select those ready, always pick one who you are certain is willing to return to duty”.

A measure of peer pressure apparently helped to return men to duty and may have helped the psychiatrist in doing it.

Luxembourg

Another rest period was planned for the 4th AD. This time the division was located in the border region of Luxembourg and France. It lasted until the 23rd of February, 1945. During this period a few men were evacuated for “inefficiency and cumulative fatigue”.

On to the Rhine

On the 23rd February 1945, the 4th AD began another offensive. This time the objective was the Rhine River, near Koblenz. The first day of combat saw some heavy German resistance, but after the division broke through the German defensive line, it fought its way with remarkable speed to the Rhine. On this first day, 75 soldiers came in with combat exhaustion. Most of these were new replacements, signaling a new wave of “first type” combat exhaustion. After the first day, the number of combat exhaustion cases dropped to a “neglectable number”. The division was once again fighting the highly mobile warfare it was created for.

During the fighting between Luxembourg and Chemnitz (around 19th April 1945) the total of combat exhaustion cases was 332. Of these, 165 men were returned to duty after treatment.

Mericle describes the next move, to Czechoslovakia, as follows:

“In a march of about 40 miles into enemy territory the only casualties were vehicular in character and only one German was killed.” This statement is not completely accurate, but it shows the almost non-existence of German resistance at the final phase of the War. On May 8th, 1945, the German Army capitulated, marking VE-day.

Totals

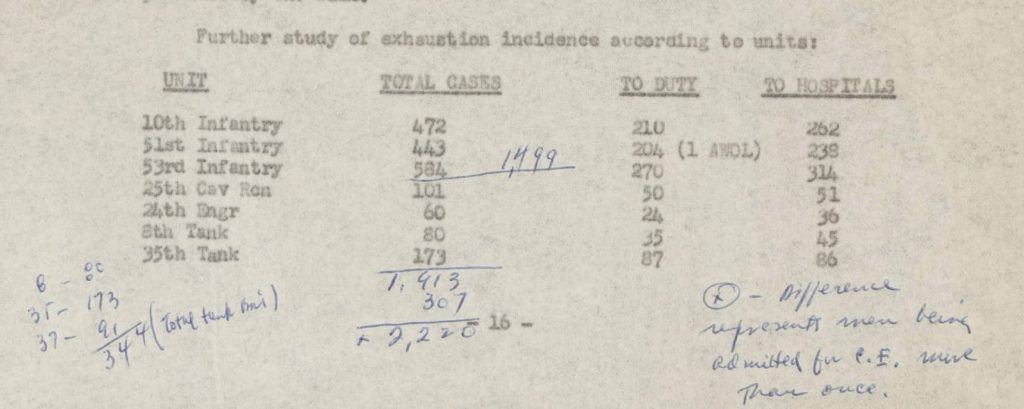

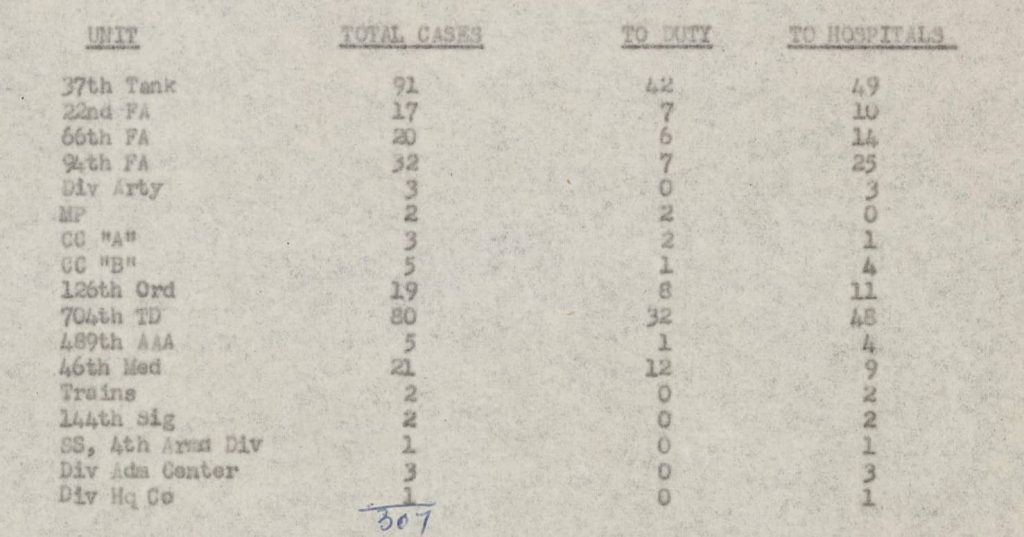

The total number of combat exhaustion cases in the 4th AD are shown in these tables, created by Major Mericle:

The number of combat exhaustion cases from the 46th AMB is shown as 21. In my research, I have found a total of 41 soldiers from the 46th AMB who are reported as evacuated for SLD. So roughly half of these are for combat exhaustion.

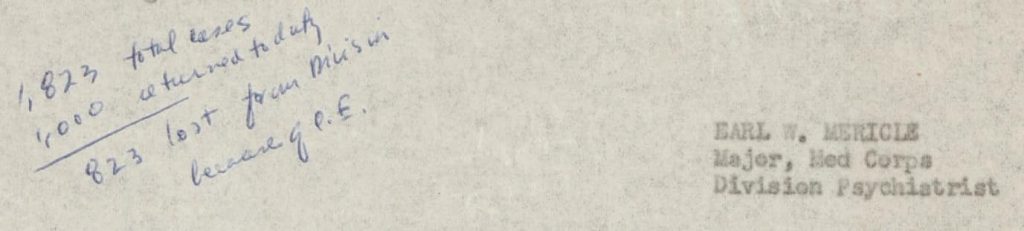

The total number returned to duty is noted in a handwritten addition to the report:

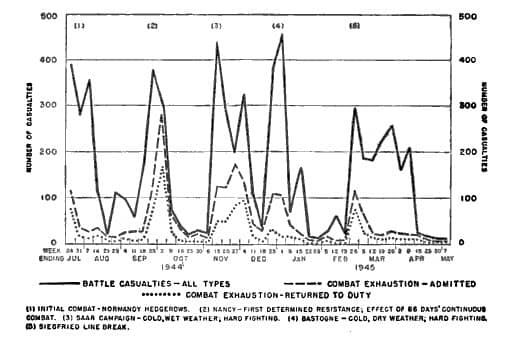

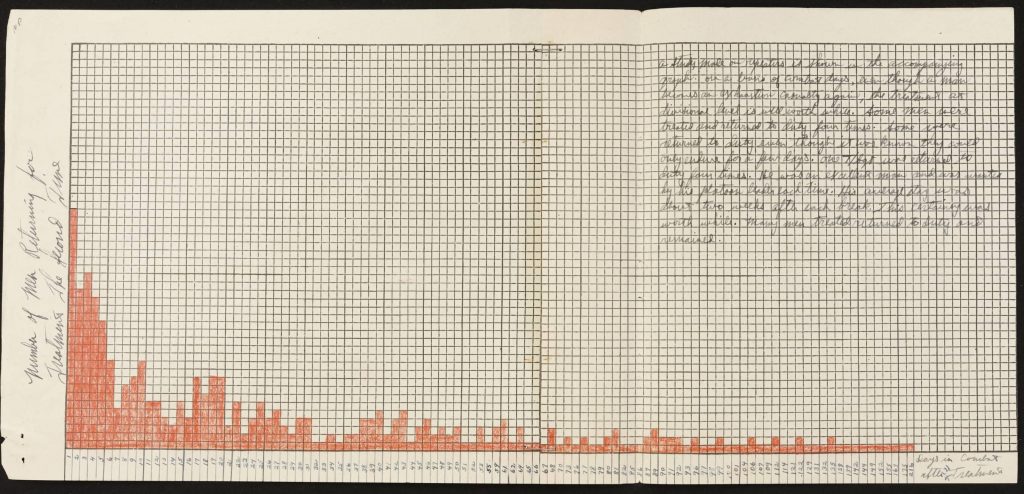

The report ends with two diagrams. The first shows the number of casualties in the different months of the War. Mericle noted that there are five peaks in the number of combat exhaustion cases, corresponding with the different tactical situations. I have used the same table, but taken from one of his articles in The Bulletin of the U.S. Army Medical Department, as it is much clearer.

The second diagram deserves a thorough study. It shows the number of days a soldier was re-admitted for combat exhaustion again after he was returned to duty following treatment.

It shows that many were re-admitted within days of being returned to duty.

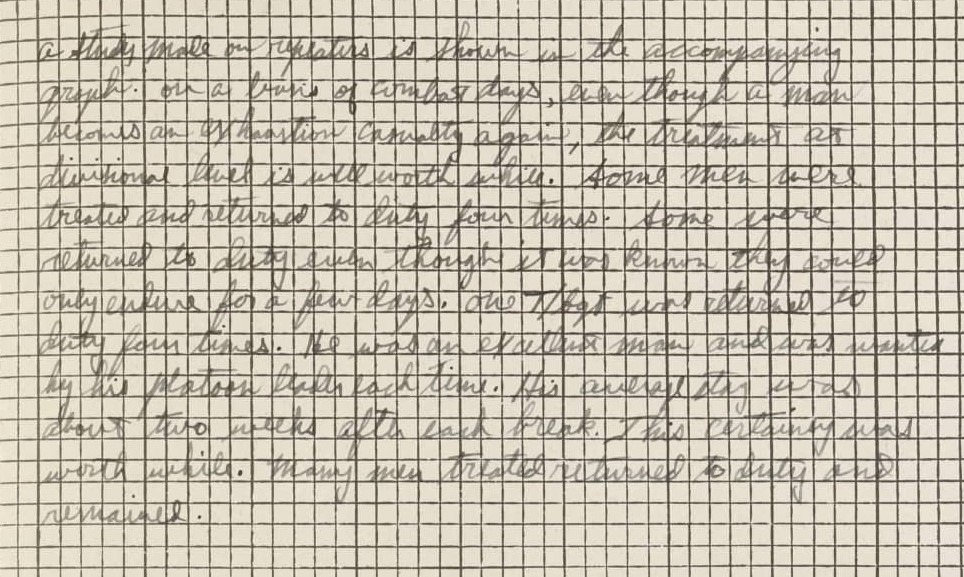

The handwritten note on the top right corner is perhaps the most emotional piece of reporting in my research. Major Mericle notes that, even if soldiers were only able to take another few days of combat, this was a success. Part of this rationale was that their return to duty filled a vacant spot, that was often not possible to fill as (well trained) replacements were very scarce.

Major Mericle describes one soldier who was returned to duty four times (!) after an equal number of treatments for combat exhaustion.

In my research, I have only found one (medical) soldier who is reported evacuated for SLD four times. His name is Emmett Davis. I have no way to prove that this is the soldier Major Mericle is writing about, but it is possible.

Whoever the described soldier was, I can’t imagine being returned to duty four times after being evacuated for combat exhaustion. Four times of having your nerves frayed by combat, four times being pushed beyond the breaking point. To me, it is simply heartbreaking.

Reflection

It is very important to note that the numbers reported in this article are the cases that were admitted during the War. They do not show all the psychological wounds sustained by US soldiers in WW2. They also do not tell us anything about the psychological wounds that veterans brought home after the War. Wounds that often did not (fully) heal.

It is often held that, what we now call PTSD (Post Traumatic Stress Syndrome), is the same as what was called shell shock during WW1, and combat exhaustion during WW2.

I believe these terms point towards the same underlying problems, but they are not synonymous. One of the most important differences is that both shell shock and combat exhaustion described, what was thought of as an acute problem, what we now might call Acute Stress Disorder. By definition, PTSD patients experience their symptoms for more than a month, and often much longer. We think of PTSD as a more chronic disease. Accepting the existence of the long-term consequences of traumatic experiences has changed our understanding and treatment of this problem. Also, the symptoms of the different types of combat exhaustion were very different, as described earlier. The symptoms of the first type of combat exhaustion resemble what we now think of as PTSD the most: anxiety, startle reactions, etc. The symptoms of the “Old Sergeant’s Syndrome” resemble many of the symptoms people have when they are suffering from a “Burnout”: irritability, loss of interest, and efficiency.

Another major difference is the explanation we have for the root of the problem. During WW1, it was thought that the problem was caused by (physical) damage done to the nervous system by artillery barrages. Hence the name shell shock.

This changed to a more psychological-based explanation in WW2. Here the physical hardships were deemed factors that accelerated the problem and made soldiers more susceptible.

Finally, many veterans were diagnosed later in life with PTSD who were never treated for combat exhaustion.

I think we should therefore be careful not to call combat exhaustion and PTSD synonymous.

Now we understand PTSD to have effects on both our physical and psychological wellbeing. Some even find that it describes a problem of not only our body and our psyche but most of all the soul, as writer Edward Tick does in his book War and the Soul.

To me, as a doctor, this insight has broadened my understanding of PTSD. Thinking of PTSD as a wound of the soul makes us think of it in new terms, requires us to ask different questions, find new answers and consider new methods of treatment and help for those who suffer from PTSD.

Pingback: Tec5 Joseph N. Korzeniowski - Part 4 - Patton's Best Medics