In 1992, Frederick B. Lea recorded his experiences of April 1945. During this month, men of the 4th Armored Division witnessed the horrors of the Holocaust firsthand when they overran two concentration camps: Ohrdruf and Buchenwald. Lea was a Captain during the War. He served as company commander of the Headquarters Company, 46th AMB; as Battalion Supply Officer (S-4), and as Division Medical Supply Officer.

In the article Recollections of a Liberator – Captain Frederick B. Lea, Captain Lea describes his experiences visiting these camps. The article is part of the Frederick B. Lea collection of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, Washington D.C.

This document opened my eyes to a whole new perspective of the story of the Holocaust: the experiences of the liberators. The way he described the sights and smells of the camps grabbed me. He showed me the dehumanization, the incredible brutality, and omnipresence of death that were part of the camps. And yet, amidst these inhuman scenes, he also found an unbelievable human story: the liberation of one special resistance fighter from Luxembourg.

Reading this document for the first time in 2013, made me want to know more about the author, and the men he served with. It set me on a path of this continuing research. I am forever grateful to Captain Lea for offering me these experiences. They truly changed my life.

In this series of three articles, I am going to take Recollection of a Liberator as a guide in writing the stories of the liberation of Ohrduf (part 1), the liberation of Buchenwald (part 2), and the story of Buchenwald prisoner 21082, the resistance fighter from Luxembourg: Paul Sand (part 3).

I would like to offer a word of caution. The stories, photos, and films that I have included in these articles are shocking and may not be suitable for every reader.

Recollections of a Liberator: Ohrdruf

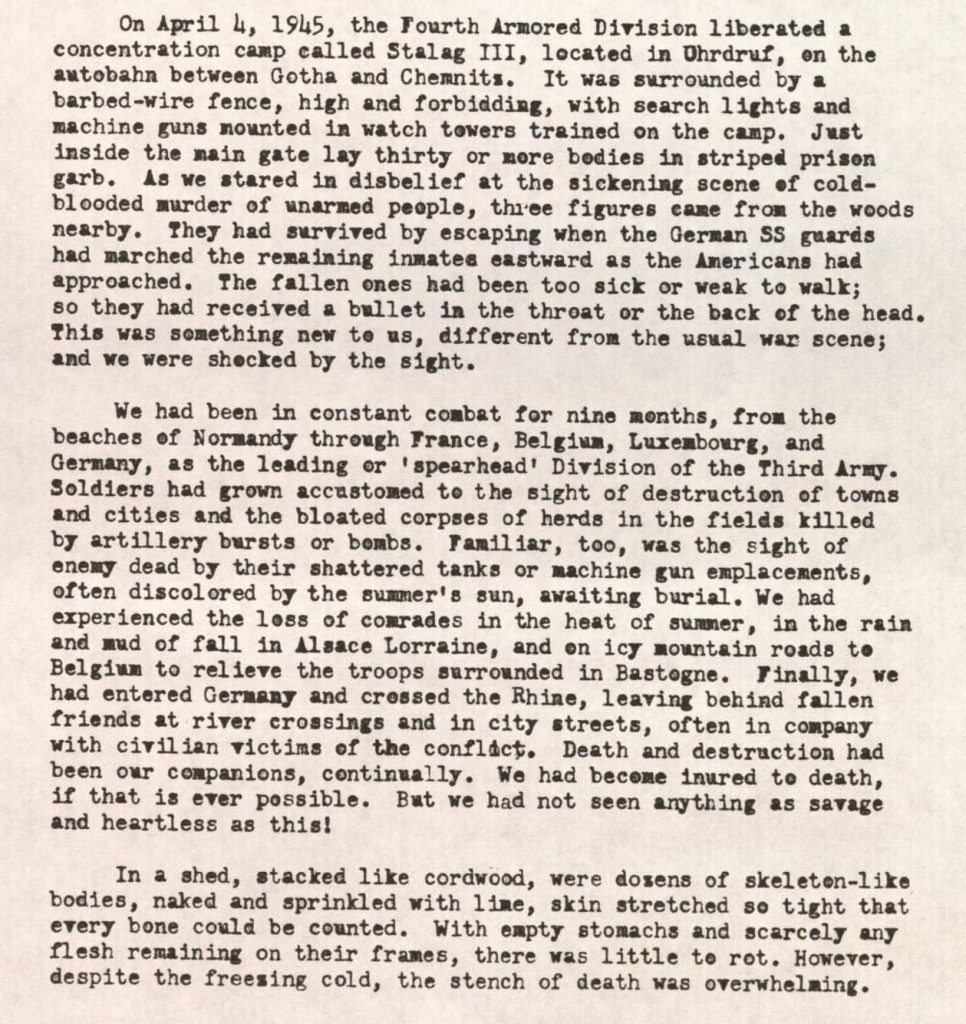

Here are the parts of the document that deal with Ohrdruf:

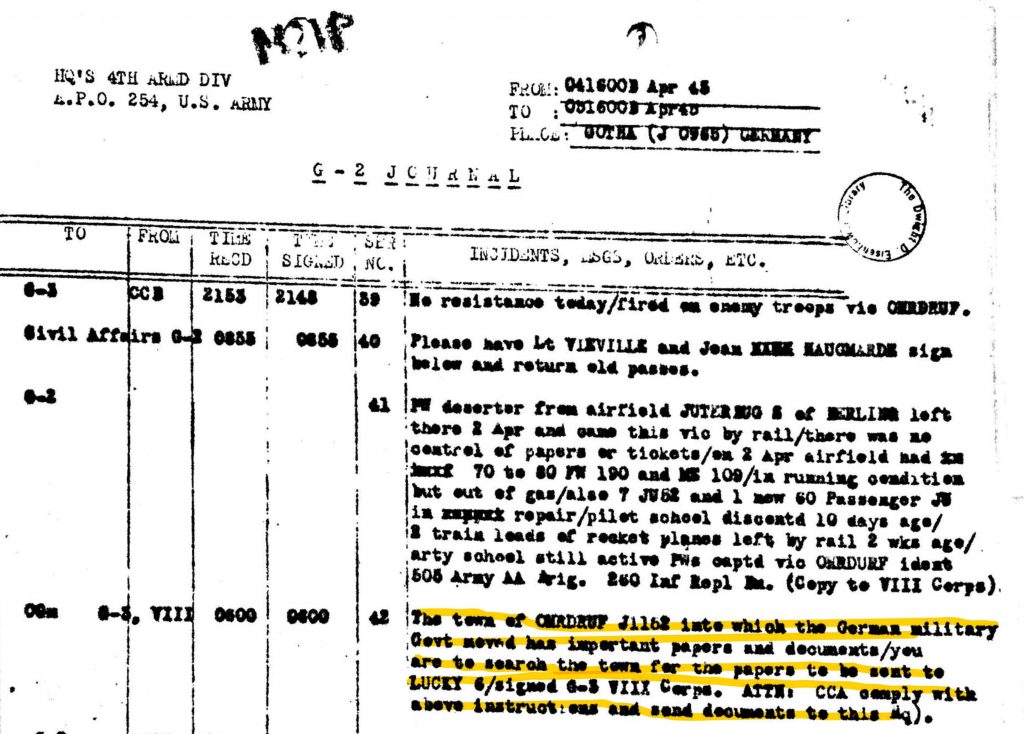

In these segments of Recollections of a Liberator, Capt. Lea describes some specific facets of what the Americans encountered at Ohrdruf: the fence and watchtowers, the bodies in the camp, and the disposal pit. In the rest of the article, I will give you a more detailed look at these, and other parts of the story of Ohrdruf.

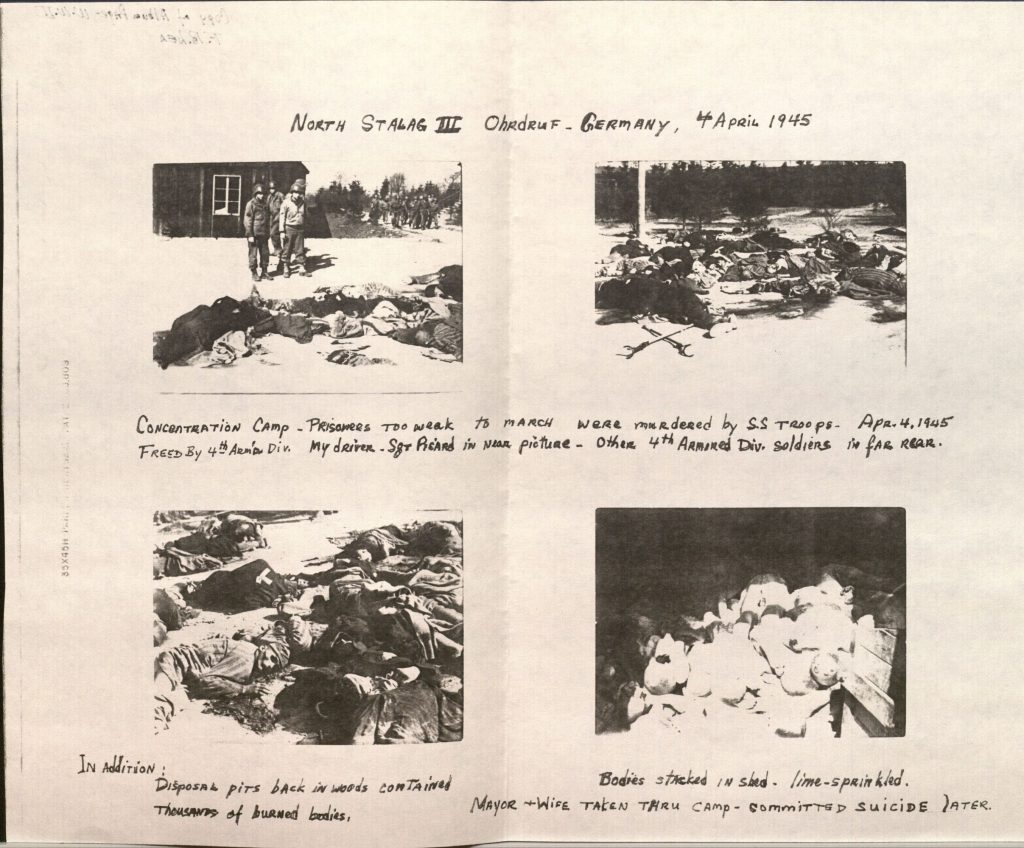

April 4, 1945.

After capturing the city of Gotha, units of the 4th AD (the 8th TB and 53rd AIB) and 89th ID were ordered south to capture the town of Ohrdruf. The primary goal was the capture of a German communications center rumored to be in the vicinity of the town.

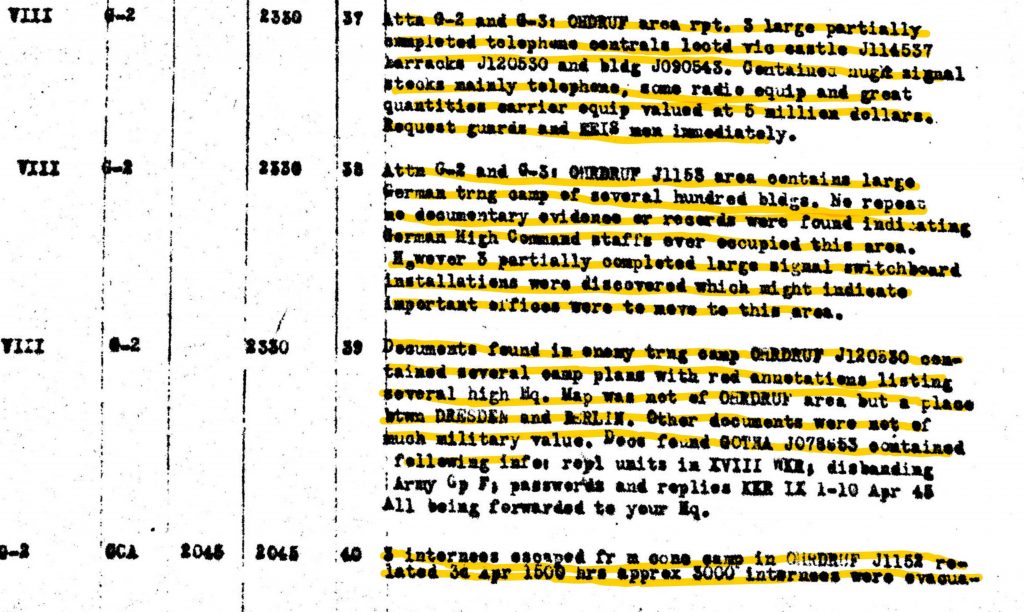

As the G-2 Reports of the 4th AD show, the troops did find the communications center.

On the road from Ohrdurf, on the search for the communications center, they encountered many bodies on the side of the road. These bodies, clothed in thin prison garb, were in terrible, emaciated condition. The true meaning of these sights would only become clear after the Americans discovered the camp.

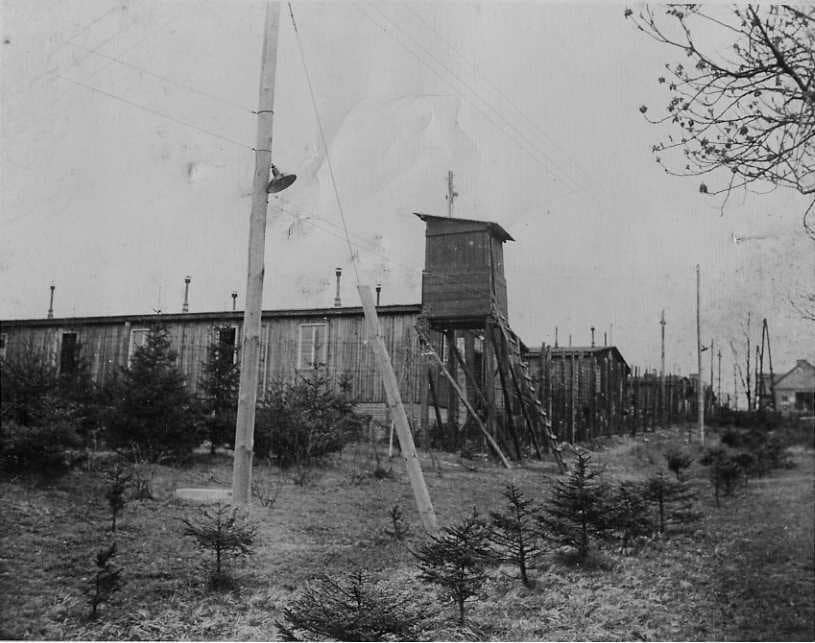

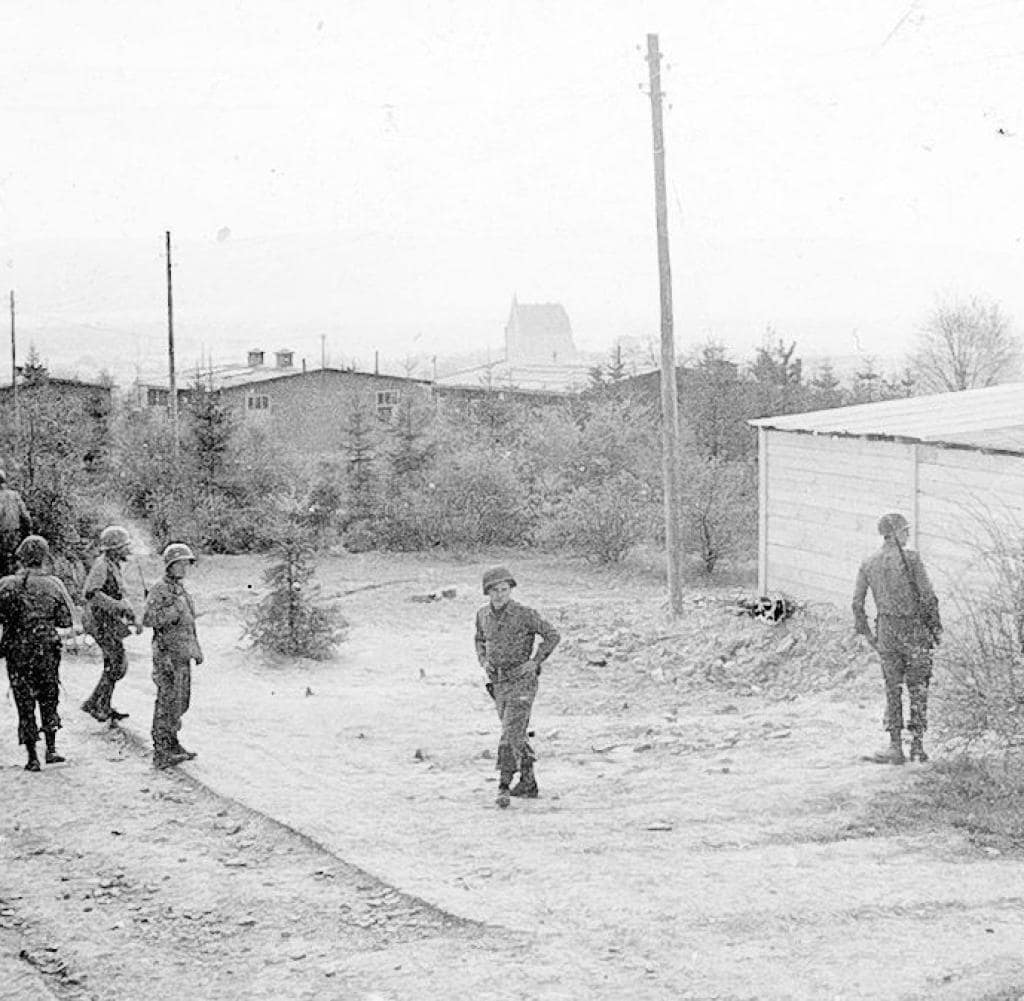

At the end of the afternoon, the first American troops came across the double barbed wire fence, the watchtowers, and the barracks of the approximately 30 acres large compound of the Ohrdruf concentration camp.

The Camp.

After the bulldozer tank of tank commander Bill Jenkins pushed the gate open with its blade, the first GIs entered a scene unknown to them. They had no significant previous knowledge of the existence of the concentration camps, so they were completely unprepared for what they were about to experience.

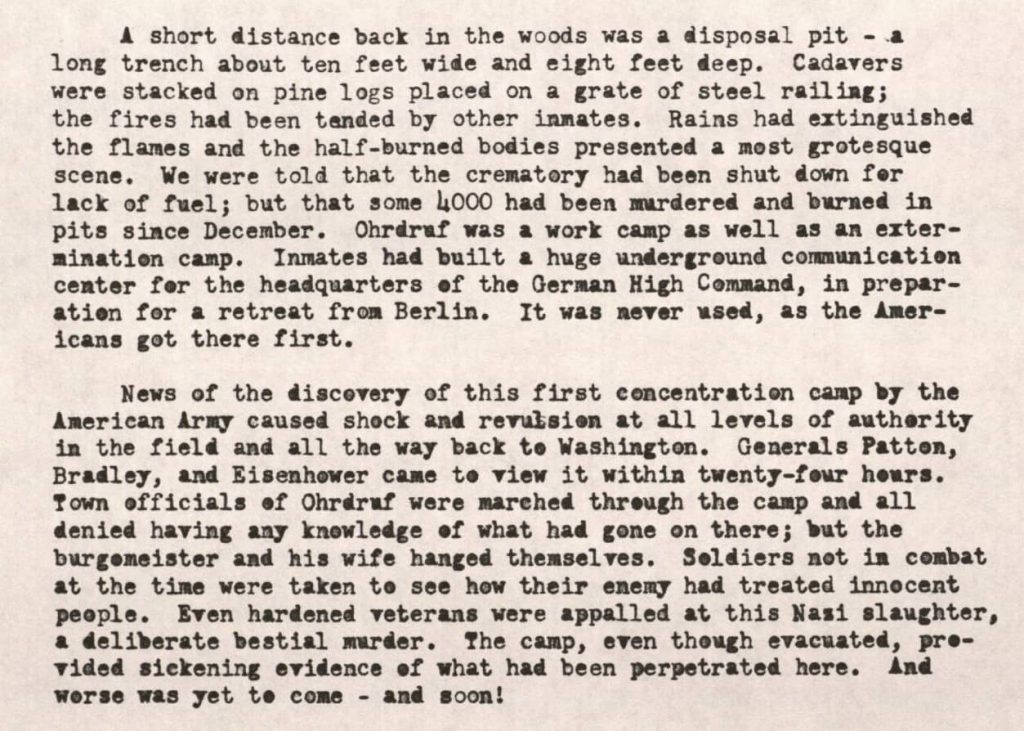

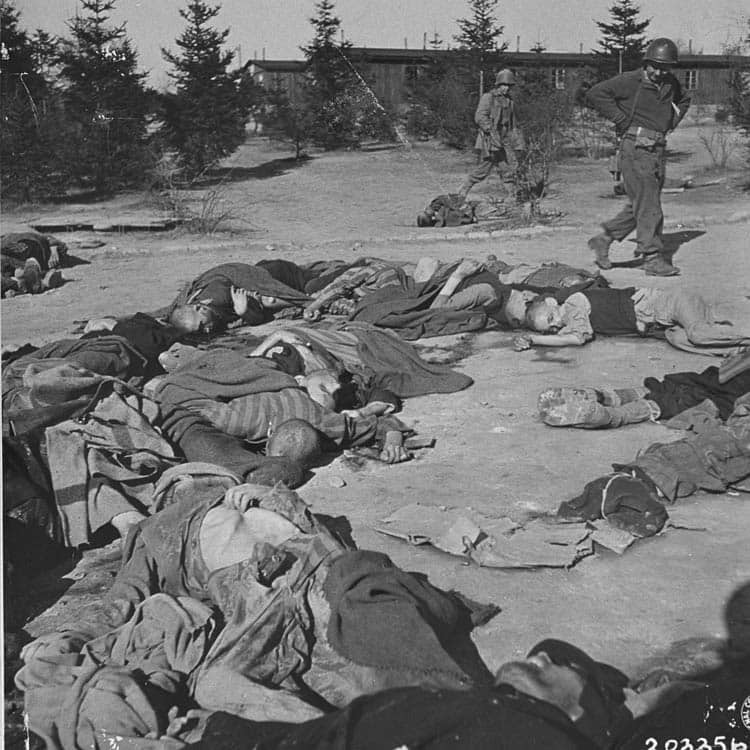

A short distance from the gate they found around 30 corpses lying in a circle in an open ground in the camp. The bodies all showed signs of horrible mistreatment. They had been shot through the head or the neck.

Lt.Col. Albin F. Irzyk, commander of the 8th Tank Battalion, described it as follows:

“I got out of the jeep and walked through the woods, and the first thing I saw was this clearing. And I just couldn’t believe what I saw. I could see an elliptical circle of bodies, with the feet in and the heads out. I was absolutely stunned. I’d never seen anything like this before—never expected to see anything like it.” He recalls gasping audibly; his feet seemed leaden as he forced them to move closer. And he gasped again. “Each man had a little red spot here”—he gestured to his forehead—”shot in the head or in the throat, one shot. And these were thin, emaciated, ragged people in this elliptical circle.” The ground around the bodies was blood-soaked. To the battle-hardened Irzyk, the scene was incomprehensible. He kept asking himself, “What is this?” And that morphed into “How did this happen? But that’s step one.” The Liberators, America’s Witnesses to the Holocaust, Michael Hirsch, page 28.

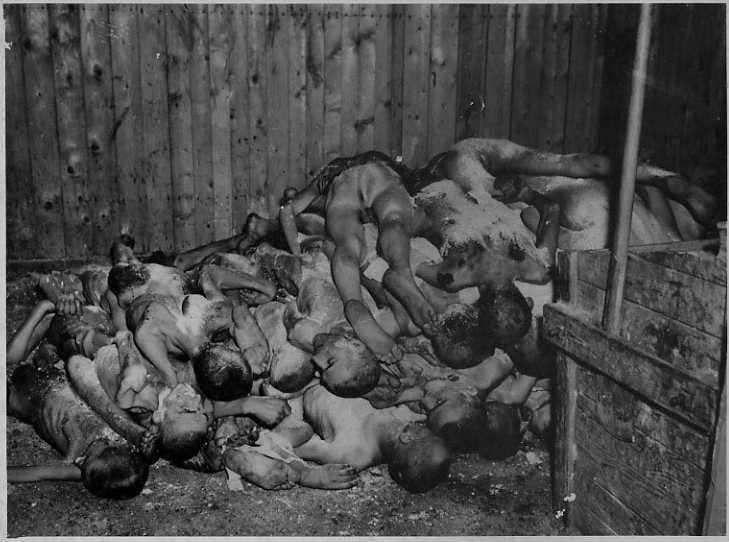

Also in the camp, the soldiers found a wooden shack, filled with corpses. Searching for words to describe these piles of bodies they often fell back to terms that they knew from their lives, GIs throughout Germany would often describe them as: “they were stacked like cordwood”.

Col. Hayden Sears (Commander CCA 4th AD) and Major John R. Scotti (Surgeon CCA 4th AD) inspect the wooden shack:

Irzyk Continues:

“And as you get to this building, this horrible smell, you open the door, and there—again—another unbelievable shock. You’ve got these bodies, probably thirty of them they’re like skeletons without clothing, but all sorts of marks and bruises, covered with lime, like cordwood, from the floor to the ceiling. Just stacked there. So you open the door and you look at—this is unbelievable! You’ve never seen anything like it. You can’t comprehend it. And that was step two.” Hirsch, Page 28-29.

In a futile effort to mask some of the stench of the decomposing of the corpses, the SS had sprinkled them with lime.

Besides these two groups of bodies, additional bodies lay all over the compound.

Harry Feinberg, one of the 4th AD soldiers that were there, looking closely at all the bodies in the compound, found one of the few survivors:

“Feinberg says, “I started walking around, and these bodies laying all over, some were clothed, some had just this striped thing. Their heads were all shaven and none are breathing. And I look, and I see one guy, his eyes back, and he’s laying. I don’t know if he was Jewish or what, but he had no face.

thing was just”—at this point Feinberg scrunches his face, looking pained. “And I see him just gasping for air, so I looked at him, so suddenly he looks up at me. I don’t know how he opened his eyes, and he says, ‘Amerikaner?’ I says, ‘Ja, Amerikaner.

The man acknowledged the information with a labored sigh. Feinberg recalls looking at the other bodies surrounding him. “Nobody else is breathing, just this one guy. I ran over to the tank, got on the horn, I said, ‘Medics, medics, come out here, I’m in so-and-so area. Get Doc Scotti here.’ He was our battalion surgeon, an Italian guy, he was the greatest. He was the salt of the earth, had a heart as big as a whale. And he came over in his jeep, and I motioned to him.

“I said, ‘Doc, the guy’s still breathing. I see him gasping.’ So Dr. Scotti, he gets on his horn and says, ‘Ambulance, come here, we’re in this sector.’ ” While they were waiting, the doctor examined the prisoner. Harry recalls how gentle he was. “Somehow he just touched here, touched here, and he listened. Didn’t take his stethoscope out, he just touched. He says, ‘Get the litter carrier —it was just two oak poles and OD canvas stretched between them. “Then Doc Scotti said, ‘Very, very carefully, pick this guy up.’ This guy didn’t have any strength, just enough to say ‘Amerikaner. ‘ So evidently he was one of the guys who knew that we liberated him. But that’s the only one I saw.

After helping rescue the lone survivor, Feinberg and some other men from his unit began to walk through the camp. “All of us took our handkerchiefs out, and we had to cover ourselves. It was impossible to breathe because the odor was terrible. At one point, I even went over to one of the barracks. I opened the doors, and there’s bodies laying over these wood beds, two-decker beds. I had to close the door. Dead, dead. I didn’t go inside; I couldn’t go inside, They were just, all of them the same, heads shaven.” Hirsch, page 33-34.

(Major John R. Scotti by this time had been promoted to the surgeon of Combat Command A, 4th AD, and was no longer battalion surgeon).

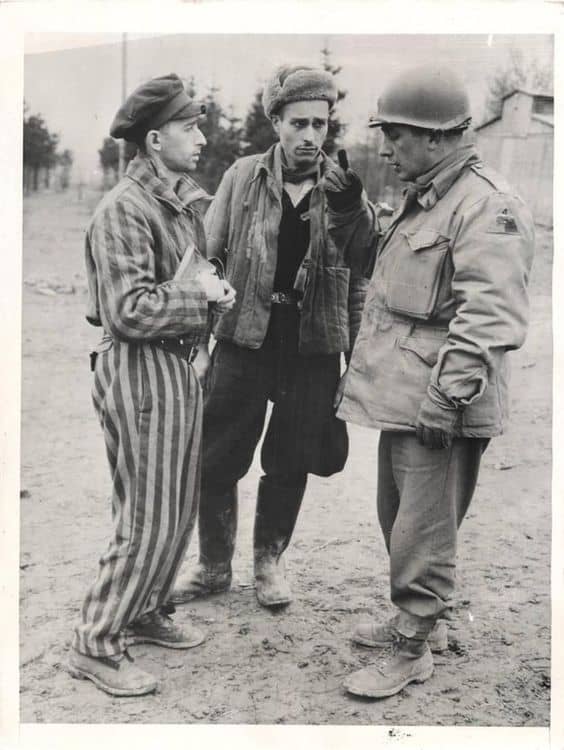

Major John R. Scotti talking to survivors at Ohrdruf:

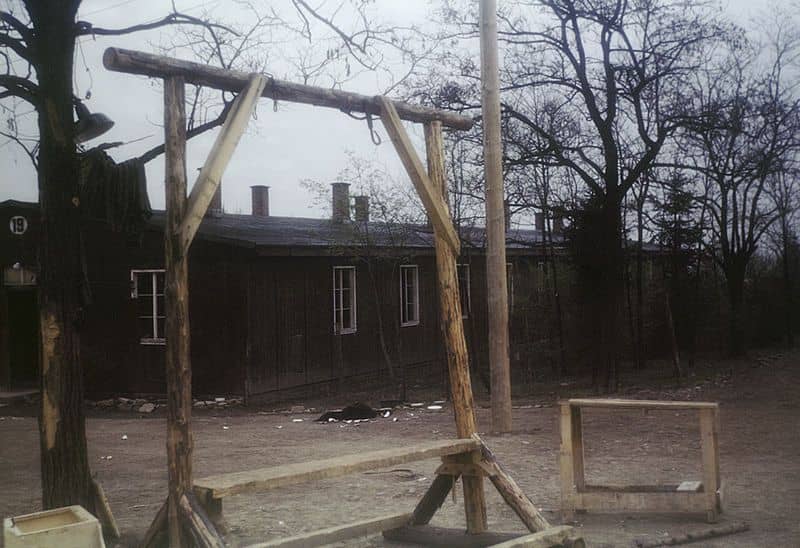

Further proof of the SS brutality were the gallows and the beating block that were found in the camp.

By this time a handful of survivors emerged from their hiding places, where they had hidden to escape the death march. They were able to explain to the Americans about the camp. Capt. Lea remembered three survivors. Some photos show a few more survivors.

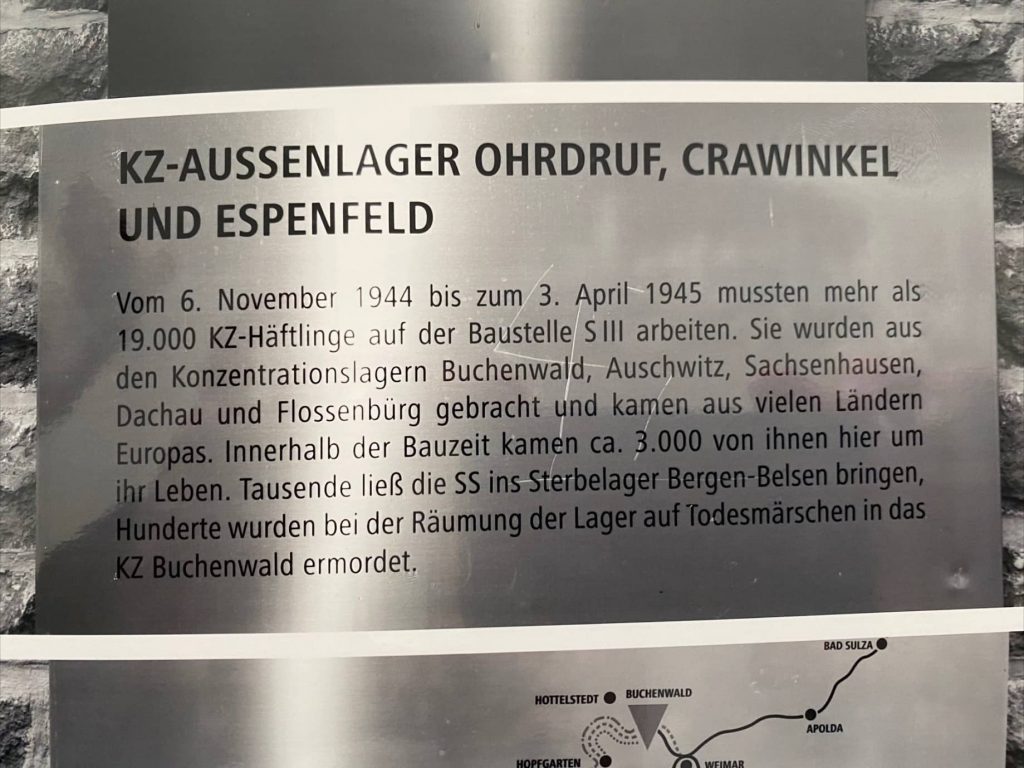

According to the USHMM Encyclopedia of the Holocaust Volume 1, Part A, page 402-403, Ohrdruf had been established in November 1944 as a sub-camp of Buchenwald.

The SS, referred to it as “(Aussen)Commando SIII”. The SIII is often mistaken for Stalag (or Stammlager)III. However, the term Stalag or Stammlager refers to POW camps. It does not refer to concentration camps.

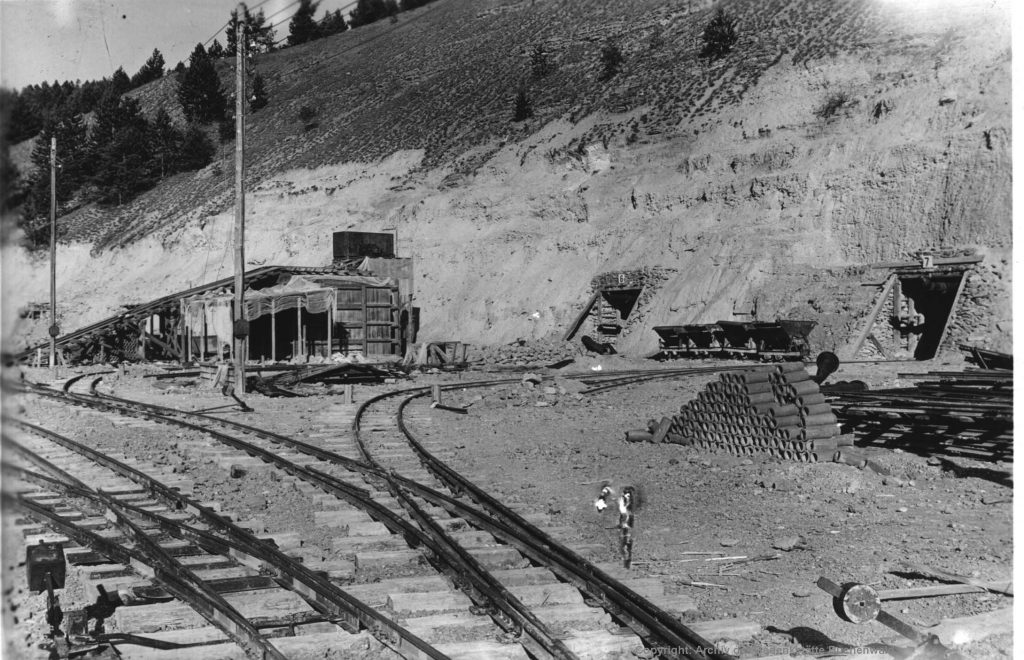

The victims were brought there to construct the communications center in the Mühlberg castle nearby and underground tunnels in the hills flanking the Jonastal valley. It is believed that in these tunnels a new headquarters for the German High Command or even Hitler was planned to be constructed. It seems that SIII was the codename used for the construction projects.

Castle Mühlberg:

Ohrdruf camp with Castle Mühlberg in the distance:

Tunnel construction in the Jonastal valley:

Sometimes the camp is called Ohrdruf Nord. This name dates back to the First World War when there was a POW camp at this site called Ohrdruf Nord (there was an Ohrdruf Süd POW camp nearby). As the prisoners of the concentration camp were housed in the barracks of the former POW camp used in World War One, the name lingered.

World War One POW camp/ Kriegsgefangenenlager:

At the height of the camp’s existence, there were around 11,700 prisoners kept there. An estimated 5,000 prisoners died as a result of starvation, diseases, and the torturous treatment by the SS-guards although the numbers vary in different sources.

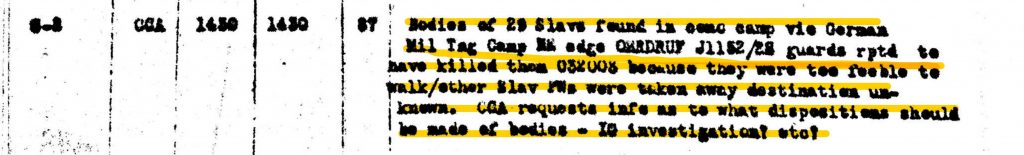

When the Third Army advance towards Ohrdruf threatened to overrun the camp, the SS started to march all prisoners, that were still physically able, towards Buchenwald in one of the death marches. All prisoners who were too weak or injured to march were shot. These were the corpses found on the ground in the camp. Anyone unable to complete the march was also murdered. The bodies found on the side of the road, driving towards the camp, were of victims of the march.

The bodies in the shack had died before the evacuation of the camp. They were gathered in the shack to be transported later to the burial and cremation location at a short distance from the camp.

Disposing of the bodies.

“Then we went up to a like a hill, it was, where they burned the bodies. They didn’t have ovens at Ohrdruf. And we could see the charred bodies. And in the background there were like piles that you would think it was dirt or it was white like snow. It were mounts of ashes of the bodies that were burned. God knows how many hundreds of bodies were burned up there.” David Cohen HQ/46 ( 1.07.43h.).

Lt.Col Irzyk also visited this site:

“Lieutenant Colonel Irzyk, deeply affected by what he was seeing at Ohrdruf, was keenly aware that his men were watching for his reaction to the horror, and he managed to keep himself from vomiting. “Then, as we roam around, the third step was the disposal pits. And by that time, the pattern emerges. You know now what this is. This is totally unexpected, you never heard anything about it, and then suddenly you’re confronted with it. This is unbelievable. It makes an impact that is unforgettable.”

While the horror of a pit filled with the decomposing bodies of slave laborers is incomprehensible, Irzyk saw something worse as he continued to explore Ohrdruf. “The cadavers were stacked on a grill of logs and rails, and firemen with their spruce and pine kept the fires hot and blazing.” Later, he learned that captured SS guards had told interrogators that between December and April, perhaps two or three thousand corpses had been burned in the woods near the camp. The evidence was all around. “The ash was shin high, and the skulls were all over the place. We saw fragments of skin that had not burned.” The Liberators, America’s Witnesses to the Holocaust, Michael Hirsch, Page 29-30.

Cremation of the bodies:

The SS had first used this site for burial in mass graves. When the Third Army fought its way towards Ohrdruf, the SS began cremating the bodies on this improvised, grill-like, crematorium. When the Americans arrived at Ohrdruf, this process was incompleted. The fire was still smoldering and in some of the mass graves, parts of bodies were still present. This shows us that the SS simply ran out of time and were unable to erase all the evidence of their crimes.

Opened mass graves:

First reactions of the liberators

“We arrive at the camp entrance of Ohrdruf.

At the gate, seven American soldiers lay sprawled in the mud, eyes wide open, sightlessly staring up at the benign blue sky.

Their faces are set in fixed grins of pain, like stone-cast gargoyles. Their bodies lay frozen in stiffened positions of intense activity, death numbed fingers glued to silent gun barrels.

There they lay, no longer to dream of home, dear things war blotted from their hearts. Drowned souls, sunk too deep in death’s slumber for human tenderness.” From Bastogne to Bavaria With the Fighting Fourth Armored Division 1944-1945: Scenes from the War and Holocaust, Charles E. Wilson, page 287.

Here Corporal Charles E. Wilson, chaplain’s assistant in CCB, 4th AD, describes his first experience at Ohrdruf as he sees the American soldiers’ reaction after they had visited the camp.

Driving to the camp, Wilson noted the beauty of the German countryside. It reminded him of Beethoven’s Pastorale:

“If ever something grand and noble should come out of Germany, it should happen here.” Wilson, page 286.

What he saw in the camp shattered his previous thoughts:

“The sickening stench and the macabre sight overwhelms me. I feel dizzy. My eyes become unfocused and everything before me blurs out. I hold my breath as I stagger back to solid ground.

I become part of a slow moving exodus of soldiers, fellow witnesses, fading away from the unbearable evidence of human cruelty that would remain in our memories as long as we live.” Wilson, page 290

Captain Jack Holmes noted the following:

“A brooding silence prevailed among the soldiers. They seemed reluctant, out of rage or respect for the victims, to say a word. “Some of the men were crying,” Captain Jack Holmes of the 4th Armored Division recalled. “Others were wandering around like lost children.” Holmes glanced at one of his friends and noticed his palms were bleeding because “he had shoved his fingernails in them so hard.” Hell Before Their Very Eyes: American Soldiers Liberate Concentration Camps in Germany, April 1945. John C. McManus, page 15.

Corporal Charles E. Wilson saw a similar reaction:

“A tanker is standing next to me. His eyes give expression of great anger. He looks down at the palm of one of his hands. His palm is bleeding, his anger so intense that his fingernails dug into his palm, drawing blood.

A stigmata in which bleeding anger fights with the knowledge of the awesome, unjust sufferings of others.” Wilson, page 288

Lt.Col Irzyk found the words to explain his own reaction:

“Lieutenant Colonel Irzyk was a consummate military professional who had seen a great deal of combat since the previous summer in Normandy. Like any commander, he was trained to maintain an even keel, but he knew that was an utter impossibility in Ohrdruf. “I had seen the most horrible of wounds, soldiers on both sides killed, dismembered. By this time, I believed I was somewhat hardened and understood deaths on the battlefield, but the examples of the deliberate and bestial suffering and death . . . was far beyond my comprehension.” Numb and bewildered, he stood in silence, looking around in disbelief. “As I stared at the Nazi slaughterhouse, I just could not accept that human beings could have such utter and total disregard for other human beings and would callously, methodically, unemotionally exterminate them. What depravity!” Irzyk was emotionally overcome. He could not stand to see any more. “I had never before been in such an agitated state. I just had to get away.” McManus, page 16.

William Charboneau, of the 89th ID, recalled: “We thought we were hardened combat veterans. Some of us cried like babies. Some got sick. We couldn’t believe what we were seeing. It was awful.” One anti-tank gun crew took in the sights and hurried back to their truck. Once inside the truck, all of them simply sat in morose silence. “Each of us was lost in our own thoughts, each remembering what we had just witnessed,” one of the crewmen later said. “The experience . . . was etched in every face. Over and over again the same cruel, brutal memories of carnage, torture, and disregard for life flashed through my brain.” McManus, page 16.

The shock silenced most of the present GIs, while some found their voice and expressed their shock :

“The Americans going through this camp are very quiet. They have already seen much death, but they stare at this death, which is uglier and harder to look at than the death of war, with impassive faces and big eyes.

Major John R. Scotti of Brooklyn, N.Y., Combat Command A’s medical officer-in-charge, burst out in a loud voice, not speaking to anyone in particular. He just stood in the middle of the camp and shouted out what he felt and no one acted surprised to hear his voice booming out big like that.

“I tell you,” he said, and his angry voice was shaking, “all that German medical science is nil. This is how they have progressed in the last four years. They have now found the cure-all for typhus and malnutrition. It’s a bullet through the head.” Hirsch, page 33.

David Cohen, of HQ/46th AMB, witnesses Major Scotti shouting these words and described him as being hysterical when he spoke these words. David Cohen HQ/46 ( 1.06.20h.)

German citizens of Ohrdruf.

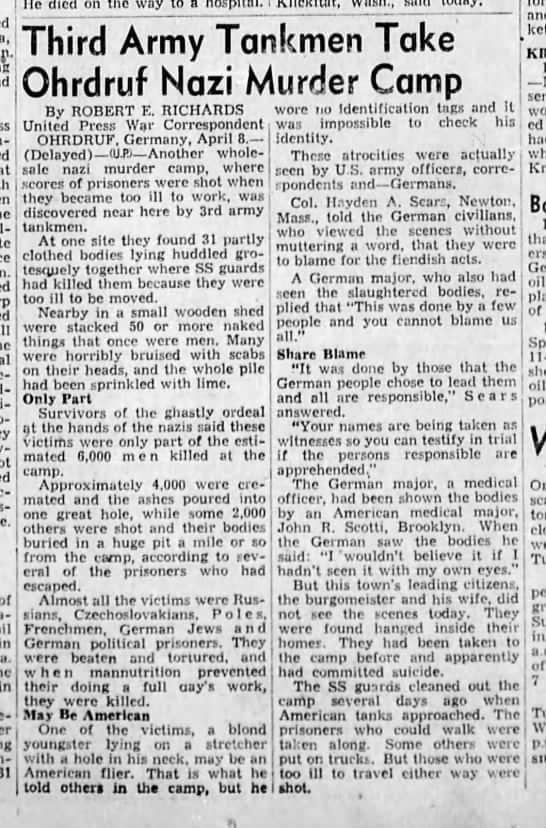

Col. Hayden Sears, commander of CCA, 4th AD, on April 6 1945 ordered a group of prominent citizens of Ohrdruf to visit the camp. This visit established a pattern that would be repeated all over Germany.

In other camps, the (American) liberators also started ordering the local population to visit and bear witness to what the Nazis had done.

Also, the response of the German citizens of Ohrdruf would be heard many times over in the weeks and months to come. It was one of disbelieve and claimed innocence. The infamous “Wir haben es nicht gewusst” (we did not know) was first heard here.

This response angered many Americans. How could they not know?! It happened under their very noses and the smell must have reached the town.

“Combat Command A’s Colonel Hayden Sears ordered his men to go into the nearby town of Ohrdruf with trucks and bring back the citizens to the camp. In his Yank magazine article, Sergeant Levitt describes Ohrdruf as “a neat, well-to-do suburban town with hedges around some of its brick houses and concrete walks leading to their main entrances. The richest man in Ohrdruf is a painting contractor who made a lot of money in the last few years on war work for the German Army and now owns a castle on the way to the concentration camp.

Harry Feinberg recalls the scene when the townspeople arrived at the camp: “They came up and had handkerchiefs over their mouths. And they dressed in their Sunday best, every one of them. The Women had nice hats, and they were taken through the camp.

The enforced tour ended at the site in the woods where ten bodies lay on a grill made of train rails, prepared for cremation. Colonel Sears said to the townspeople, “This is why Americans cannot be your friends.” Then he turned to a German medical officer and asked, “Does this meet with your conception of the German master race?” It took a few moments for a response. “I cannot believe that Germans did this.” In Yank, Levitt wrote:

The crowd of the best people in Ohrdruf stood around the dead and looked at the bodies sullenly. One of them said at last: “This is the work of only one per cent of the German Army and you should not blame the rest.

Then the colonel spoke briefly and impersonally through an interpreter. “Tell them,” he said, “that they have been brought here to see with their own eyes what is reprehensible from any human standard and that we hold the entire German nation responsible by their support and toleration of the Nazi government.”

The crowd stared at the dead and not at the colonel. Then the people of Ohrdruf went back to their houses.

The colonel and his soldiers went back to their tanks, and we went out of this place and through Ohrdruf and Gotha, where the names of Beethoven, Mozart and Brahms are set in shining gold letters across the front of the opera house.” Hirsch, page 36.

In the video below, you can watch the German citizen’s visit to Ohdruf. Due to the graphic content you have to select on the line to show that you understand this and wish to continue.

The mayor of Ohrdruf, Albert Schneider was ordered to visit also. The day after his visit he, and his wife were found in their homes. They had committed suicide. Most GIs who heard of this were sure that their suicide was an act of shame and guilt. One GI who had spent a few hours with them, heard the couple cry as they remembered their son who was killed on the Eastern Front. In the final months of the war, many fervent Nazis committed suicide over the loss of the war. The true reasons for the Mayor’s suicide were never clarified.

The visit of Generals Eisenhower, Bradley, and Patton.

The video below shows the visit of the three generals. Due to the graphic images, you have to click to show that you understand this and wish to see it.

On April 12, 1945, Generals Eisenhower, Bradley and Patton visited the Ohrdruf concentration camps. They were shown all the terrible sites in and around the camp.

Entering the wooden shack with the corpses, Eisenhower encounters David Cohen of the 46th AMB HQ. He told Cohen:

“I was sick to my stomach. The fourth time I walked in, General Eisenhower came in there, and he was green, actually green. And he looked at me and says: “God Sergeant, you have to have a strong stomach to take this.” (1.04.30h.)

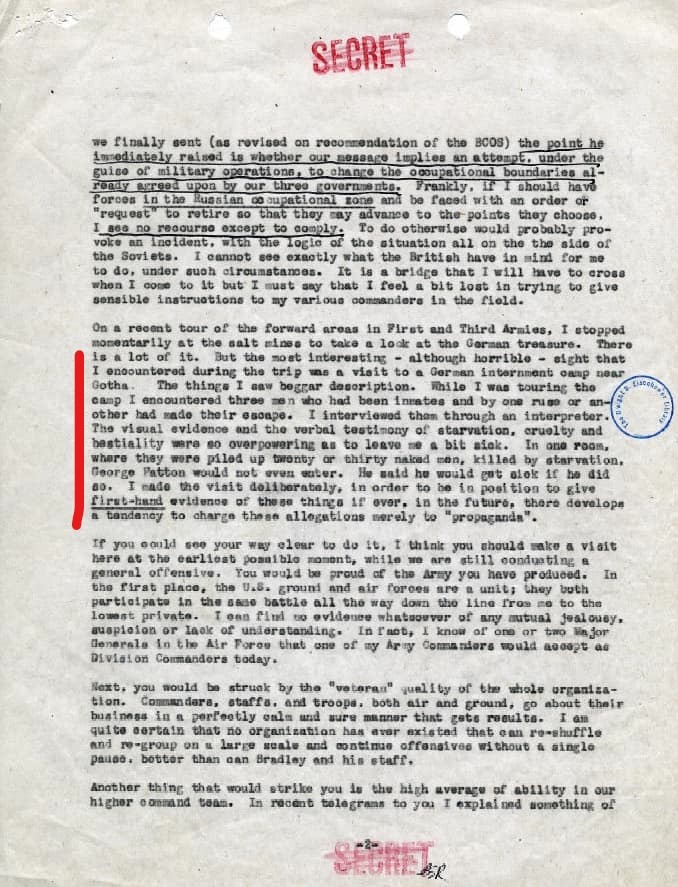

Eisenhower was determined to see everything for himself. As he wrote in a letter to General Marshall: “I made the visit deliberately, in order to be in position to give first-hand evidence of these things if ever, in the future, there develops a tendency to charge these allegations to merely “propaganda”.

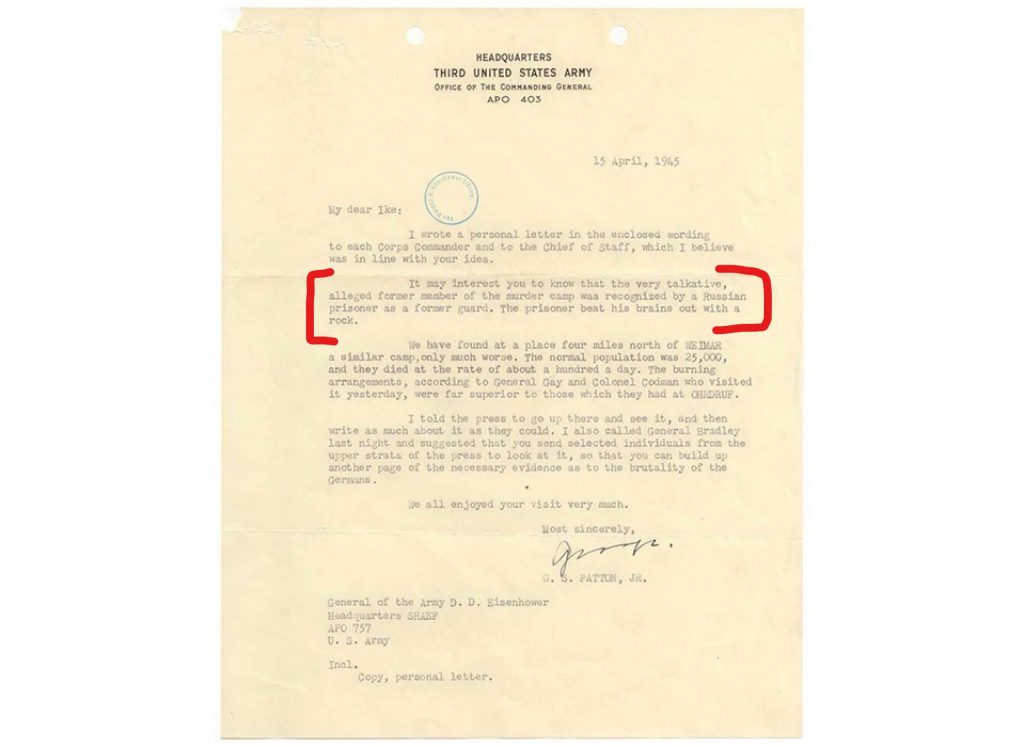

Letter from Ike to Marshall:

I still find it incredible that Eisenhower, even at that moment, already suspected that the Holocaust would be denied by far too many, and decided that he needed to visit Ohrdruf to be a witness himself.

“During a press conference a couple of months later, he admitted, “I think I was never so angry in my life. It explains something of my attitude toward the German war criminal. I believe he must be punished and I will hold out for that forever.” One of his aides described him at Ohrdruf as looking “very sick . . . and angry.” During the tour, when someone told Eisenhower about the suicide of Mayor Schneider and his wife, he replied, “That is the most encouraging thing I’ve heard of. It may indicate that they still have some sensitivities.”

Before Eisenhower left the camp, he gathered all of the GIs around him and spoke to them. “I want every American unit not actually in the front lines to see this place. We are told that the American soldier does not know what he is fighting for. Now, at least, he will know what he is fighting against.” McManus, page 24.

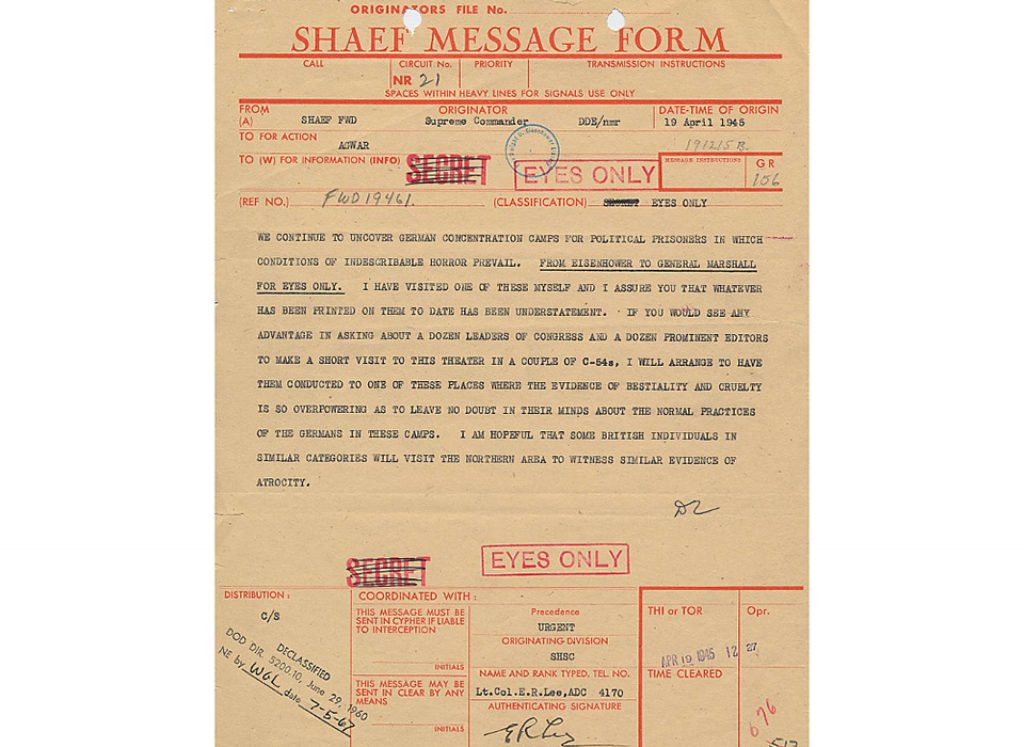

Eisenhower not only ordered as many GIs as possible to visit the camp, but he also wrote to General Marshall with the suggestion to invite some members of Congress and newspaper editors to fly to Germany to visit the site to further increase the number of witnesses who could spread the news to the American people.

Eisenhower’s suggestion to Marshall:

General Patton is reported to have been far more reluctant to visit every site. In fact, during the visit, he had to go behind one of the barracks to vomit.

David Cohen saw Patton when he climbed in his Jeep to leave:

“We went out and walked around and General Patton got up on his Jeep. He had looked in one of these shacks where the bodies were. And he came out and threw up. He didn’t even want to look at it and threw up. And he got up on his Jeep and started screaming in his high-pitched voice: “You see what these son-of-a bitches did! See what these bastards did?!…. I don’t want you to take a fucking prisoner! And there is Eisenhower and Bradley standing there, you know, with the Geneva Convention, in the background. But it just showed the anger you know?” (1.05.05h.)

The man in standing on the left of the photo, wearing a black jacket and a scarf around his neck was the person who acted as a guide to Eisenhower.

According to this letter from Patton to Eisenhower, the man was later found to be a former guard of the camp. When he was identified by a former prisoner, he was beaten to death.

Following the liberation of the camp and the visit of many GIs, the bodies that were still present in the compound were gathered and buried in a field nearby. The Americans probably made the local German population dig the graves. The camp itself was later destroyed.

Burial of the bodies:

The trauma of liberation.

The experiences at Ohrdruf changed the men forever.

“I can still taste the smell. It never left me.” David Cohen HQ/46 ( 1.04.02h.)

I encourage you to watch David Cohen’s entire interview. It is fascinating.

I have found another remarkable eyewitness account online that I encourage you to listen to. It is an interview with Lt. Col. Morris Abrams, the 4th AD Division Surgeon.

In this interview, he describes his experiences at Ohrdruf, and you can hear the effect it has had on him since. While describing the cremation site, his soft-spoken, gentle voice suddenly stops. There is a barely audible whisper. Then the recording is stopped for a moment. Even if we can’t see his reaction, the silence speaks volumes in describing the pain still felt after all these years. ( 1.51 min.)

In his book Hell Before Their Very Eyes: American Soldiers Liberate Concentration Camps in Germany, April 1945 author John C. McManus, describes the impact these experiences had on the GIs very eloquently:

“More than anything, the American liberators had to deal with the terrible memories of what they had seen, smelled, heard, and felt. Some lost their faith in humanity, others in God. Many experienced terrible feelings of guilt because of their inability to save more prisoners or to care for them properly; some felt self-loathing for their inward revulsion at the sight of them. For most, the shock and the trauma lasted a lifetime, even among the most battle-hardened combat soldiers. “The horror of that April day is still fresh in my memory,” Clifford Barrett, an infantryman and Dachau liberator, wrote more than half a century later. He and his fellow soldiers emerged from the experience “totally different men. We just could not accept that human beings could do this to other human beings. We saw hell but those people had to live and die in it.”

…

For Barrett and many others, the liberations gave meaning and definition to the costly, bitter war they had fought to destroy Nazi Germany. Amid the nightmarish circumstances of the concentration camps, they found new purpose in the agony, sacrifice, and bloodshed of three terrible years of war. Simply put, the soldiers now told themselves, “This is why we fought the war. This is why my buddies died. This is why I had to kill Germans.” The discovery of the camps elevated the trauma of combat to a high moral plane, a source of lifetime pride for an entire generation of soldiers.” Page 3-4.

Ohrdruf today.

The site of the Ohrduf concentration camp had been on a training ground used by the German Army for decades. After the War, it became a training ground again. This means that the site has not been open to the public for a long time. The Bundeswehr is turning over or has recently turned over, the site to the local authorities.

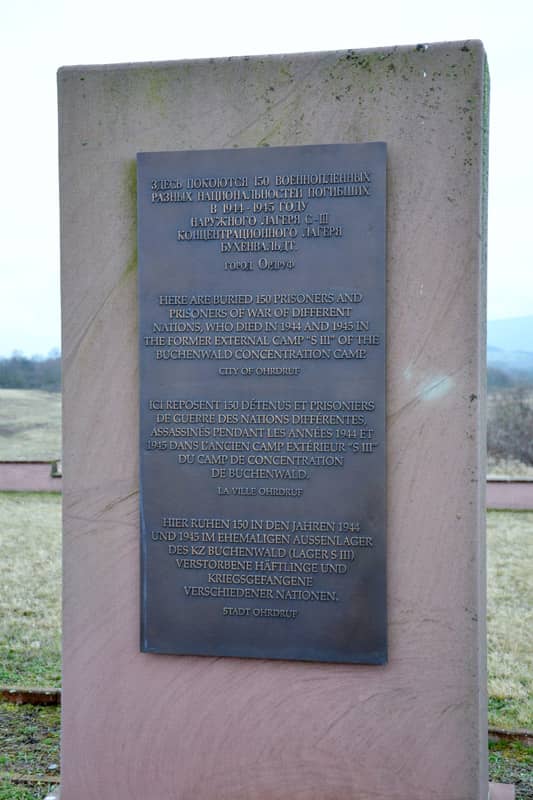

There are several monuments dedicated to the victims of “Commando SIII”:

Monument at the site of the camp (coördinates: 50.846701, 10.746764)

Monument at the site of the burial and cremation location (50.864410, 10.749974)

Monument at the site of the burial ground of the remaining victims of the camp (50.852299, 10.744827)

Monument Jonastal:

This monument is for all the victims of the SIII Commando. It is situated in the Jonastal valley, facing the site of the tunnels (50.813598, 10.873476).

I took these last photos in 2016 when I drove the route of the 4th AD through Germany in my Willys MB Jeep. At that time the other sites were not open to the public (yet). SO this was the only site that i could visit at the time.

When I returned from this trip, I looked at all the photos that I had taken and was shocked to notice the Swastika carved into the monument.

I think it is incredibly disheartening that even after all those years we clearly still have not learned the lessons of tolerance and respect for others. It also proves the continued necessity of telling the stories, so that one day, maybe, hopefully, humanity might prove that we are better than this.

Lest we forget.

Pingback: Recollections of a Liberator: the liberation of Ohrdruf and Buchenwald. Part 2: Buchenwald. - Patton's Best Medics

Pingback: Recollections of a Liberator, part 3: Prisoner 21082, Paul Sand - Patton's Best Medics

Pingback: Tec5 Joseph N. Korzeniowski - Part 6 - Patton's Best Medics