After being wounded, a casualty received first aid (Part I). Emergency medical treatment was then started by a company aid man (Part II). Now it was time to get the casualty away from the front as quickly as possible. This evacuation followed the links of the Evacuation Chain. In this part, I will take a look at evacuation within the first echelon as provided by the medical detachments.

Collecting point -vs- Battalion Aid Station

First echelon evacuation meant getting the casualties away from the front line as quickly as the tactical situation allowed.

In an infantry division, this meant evacuation to a battalion aid station.

In an armored division, battalion aid stations were not always set up during offensive operations. The speed of advance often made it impracticable to establish an aid station, only to move it further forward as the advance continued. This was especially true for the medical detachments of the tank battalions.

When no aid station was set up, the casualties were evacuated to so-called casualty collecting points. Collecting points were established on the axis of advance.

The medical detachment had personnel and equipment at the collecting point to care for the casualties. At these points, casualties awaited further evacuation by the collecting platoons of the medical company (starting second echelon evacuation).

Evacuating the wounded

So, now we know that the wounded ended the evacuation in the first echelon at either a battalion aid station or a casualty collecting point. But how did they get there?

You can find out more in this manual:

The medical manuals of the US Army divide casualties into two groups. The first group is the “walking wounded”. These casualties were still capable of getting themselves to the nearest aid station or collecting point. They were directed there by the company aid men.

The challenge for the medical detachments was evacuating the rest: the casualties who were hurt and had to be brought back.

In an infantry division, this was the job of litter bearer teams: groups of preferably four litter bearers who were sent from the battalion aid station to the front to pick up and bring back the wounded. Especially in hilly or mountainous terrain, this was a very tough job to do.

You can read more about the litter bearers here:

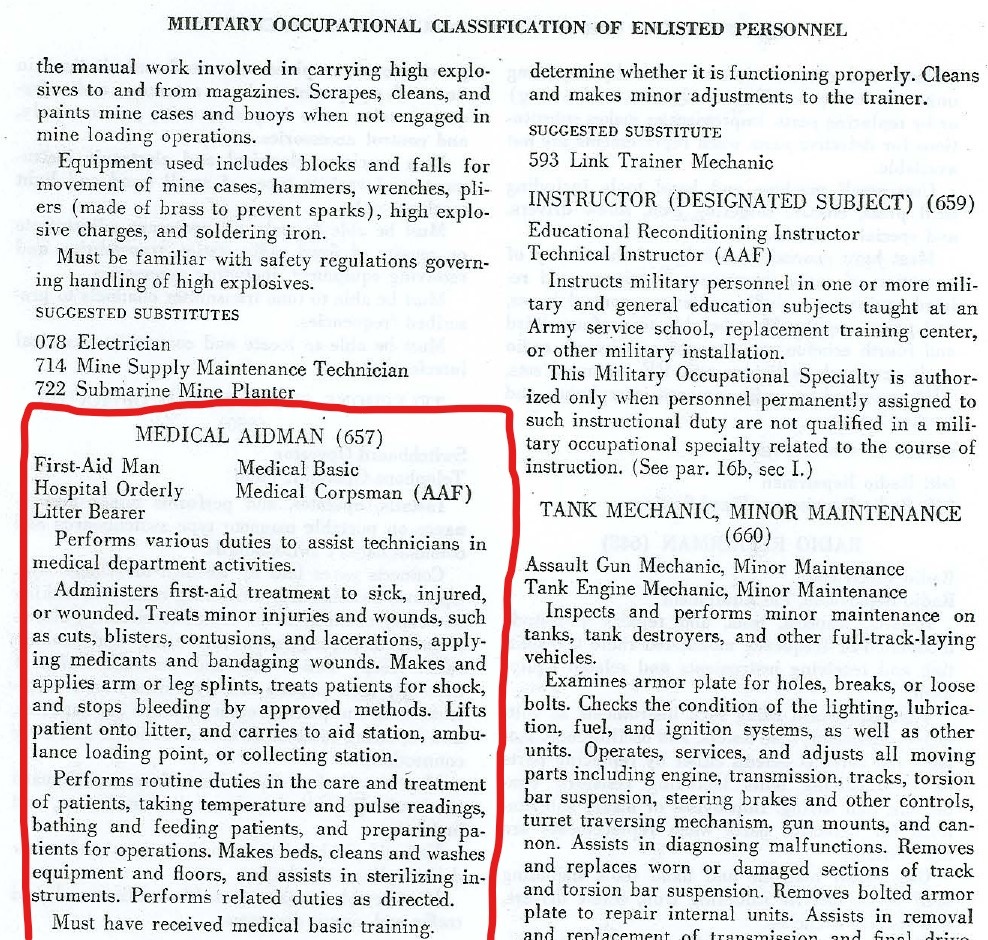

TM 12-427 Classification of Military Occupational Specialties of Enlisted Men:

And on the website of the WW2 US Medical Research Center:

Litter Bearers:

Litter Squads ordinarily consisted of four Bearers. Fewer Bearers were unable to withstand the fatigue of long or frequent carries. The function of Litter Squads of attached Medical Sections were to:

Maintain contact with the combat elements, clear the battlefield of casualties, removing those unable to walk to the Battalion Aid Station or to the pre-arranged Collecting Points. Administer emergency medical treatment, and assist the Aid Station Group in moving and re-establishing the Aid Station. Act as messenger to the higher echelon, i.e. the Battalion Surgeon, and fill out and attach EMTs to the wounded and the dead, when time and situation permitted.

Besides the litters they carried, litter bearers were equipped with a Medical Kit, Private, so they could also give some basic emergency medical treatment when necessary.

In an armored division, the only medical detachments that had litter bearers in their TO&E were the tank battalions (who had 6 litter bearers each) and the armored infantry battalions (who had 12 litter bearers each).

These ambulance litter bearer teams (as FM 17-80 calls them on page 14) were sent out with the WC-54 ambulance that was part of the medical detachments. The ambulance was driven as close to the front as possible to a location that concealed it from enemy activity. From here the litter bearer teams would go to the front and pick up and bring back the wounded on their litters. The ambulance would then bring the wounded to the aid station or collecting point.

In the other battalions of an armored division, first echelon evacuation was performed by the company aid men/surgical technicians attached to the various units of the battalions.

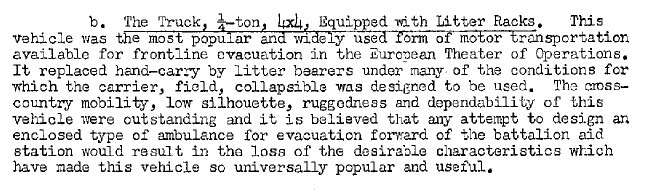

¼-ton Truck

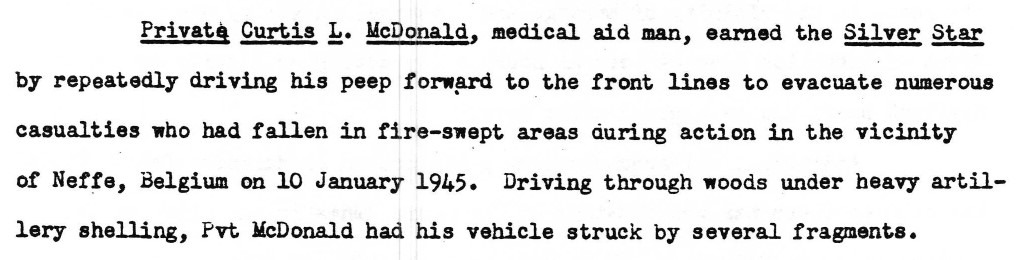

The main tool for evacuating the wounded that the medical detachments had was the ¼-ton truck. This Jeep, as we have come to know it (although the men in the Third Army called it a “Peep”), was the workhorse of front line medics. With a couple of improvised brackets, it could carry some litters. With its low silhouette and 4×4 drivetrain, it was almost ideal for the job.

From the unit diary of the 10th Armored Infantry Battalion, dated February 12th, 1945:

From the General Board on evacuation 1945:

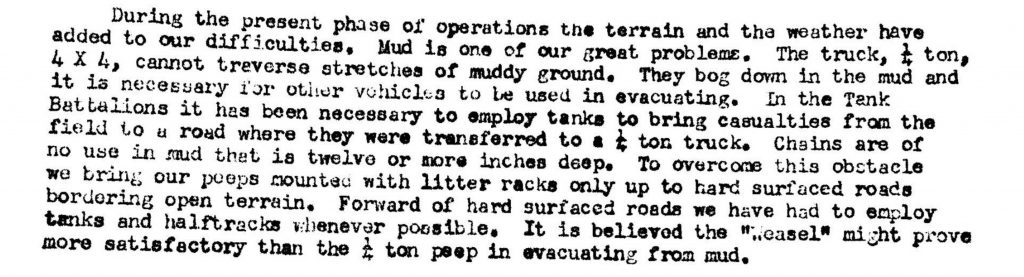

I say: “almost ideal” because the medics of the 4th Armored Division were confronted with its limitations. Starting in November 1944, the weather deteriorated so much that the ground in the Lorraine region of eastern France (where the 4th Armored Division had to slug its way to the German frontier), became such a sea of mud that even the unstoppable Jeep got stuck.

It is said that General Patton became so frustrated with the mud in Lorraine, that he demanded that in any post-war arrangement with the Germans they would be made to keep Lorraine!

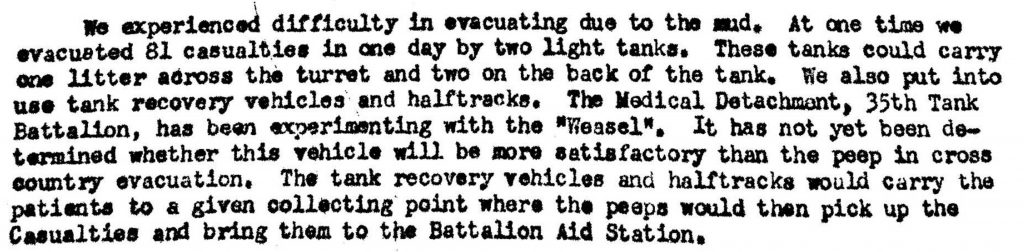

The muddy terrain became so bad that the medics had no alternative than to use M-5 Stuart light tanks as ambulances. They carried the wounded, loaded on the back of the tanks, back to the nearest road. Here the medical detachments had Jeeps and Dodge ambulances waiting for the wounded.

From the Journal of the Division Surgeon, dated November 19th, 1944:

And from the same journal, dated December 8th, 1944:

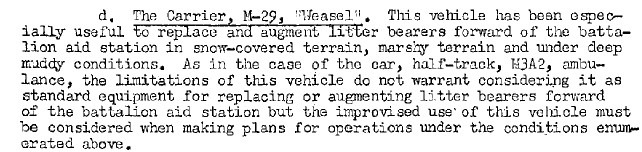

As we can see, by December 1944 the 4th Armored Division received M-29 Weasel to experiment with. These light tracked vehicles proved to have better cross-country evacuation capabilities than the Jeep.

By this time it was no longer the mud, but the snow that hampered first echelon evacuation. The Weasels also proved capable to handle this situation well.

The conclusion of the General Board on Evacuation 1945 on the M-29 Weasel:

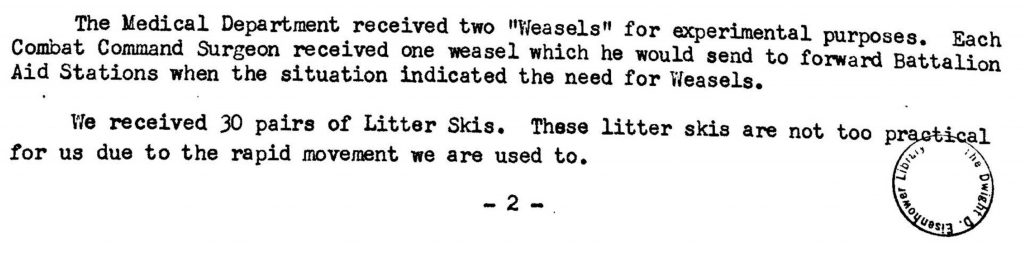

And the Journal of the Division Surgeon, dated 22nd February, 1945:

It is interesting to see that by the end of February 1945, with spring just weeks away, the Army started supplying the 4th Armored Division with Ski litters. We can see the response to their arrival was lukewarm at best… Looking at all the weather reports I have collected from all the documents in my research, the 4th AD only had two more days of snow after it received the ski litters (March 6th and 7th 1945). I have not found one document that shows they were ever used by the medics of the 4th AD.

Number of evacuees

I would be very interested to have the total number of evacuees within the first echelon of the 4th Armored Division. Unfortunately, I do not have the complete numbers for this. There are several reasons for this. I have the reported casualties treated by the 46th AMB (but this is second echelon). These do not include soldiers returned to duty by the battalion surgeons, for example.

The journal of the division surgeon has most of the number of evacuees within the division, based on the medical records the division surgeon’s section received and processed. Unfortunately, I do not have the journal complete in my records.

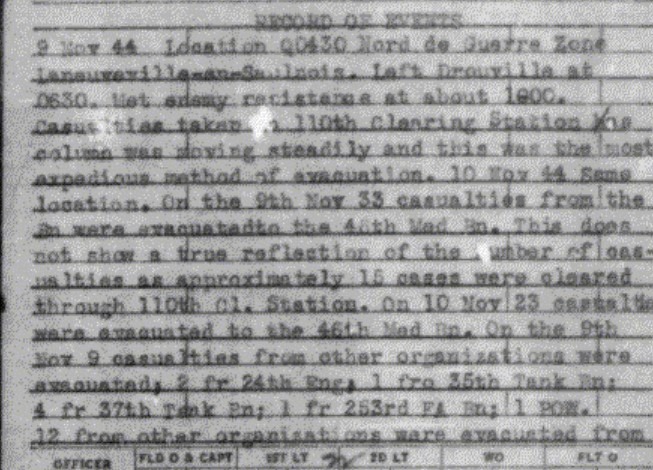

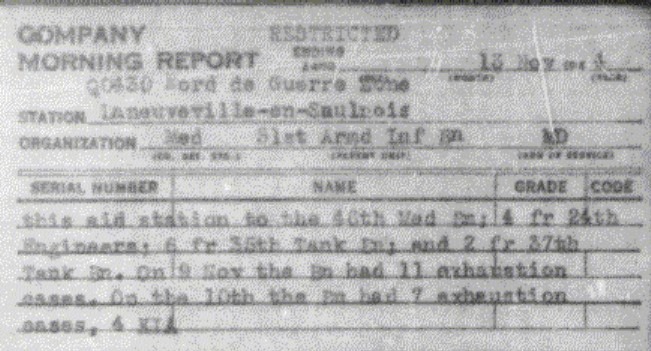

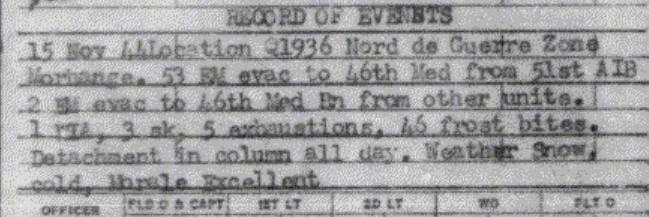

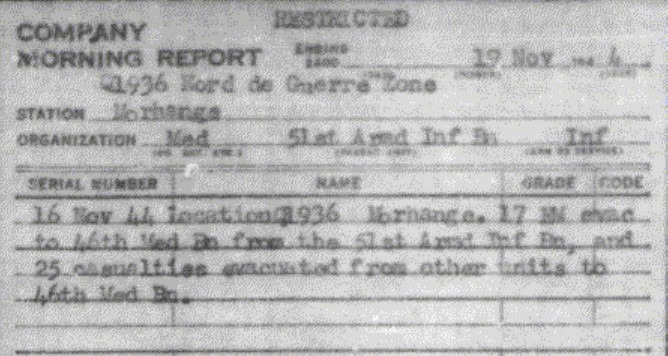

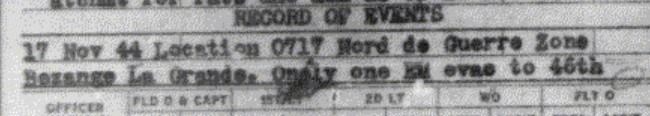

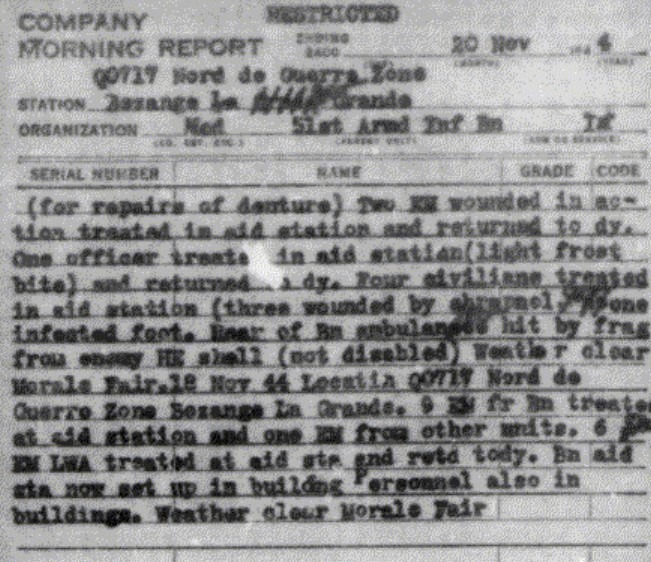

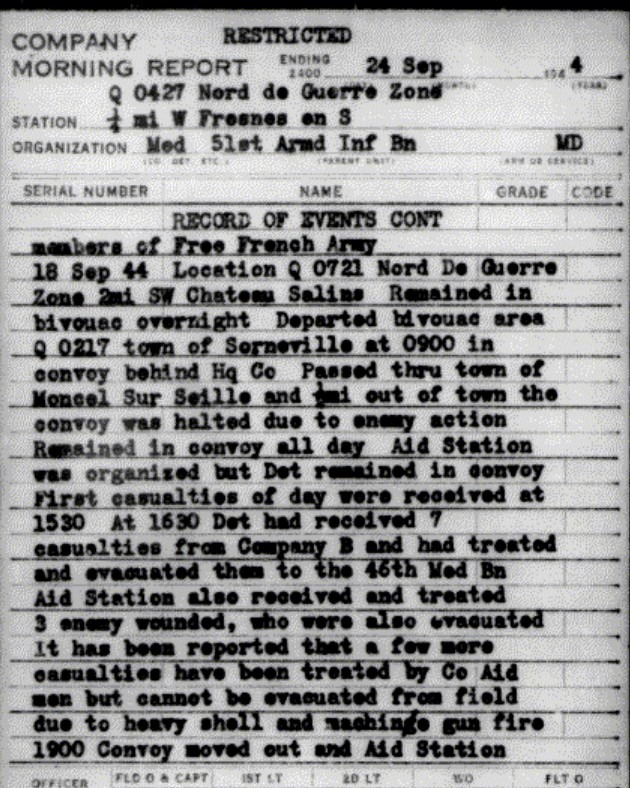

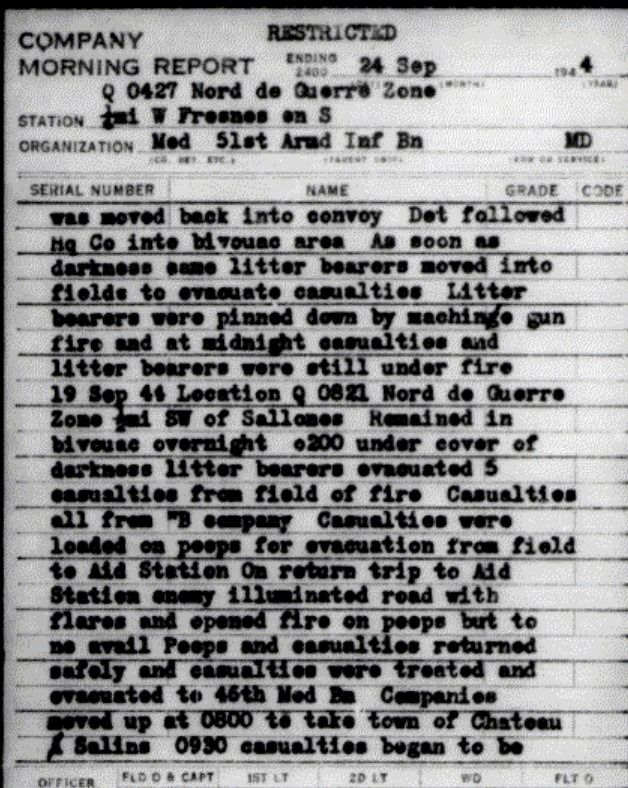

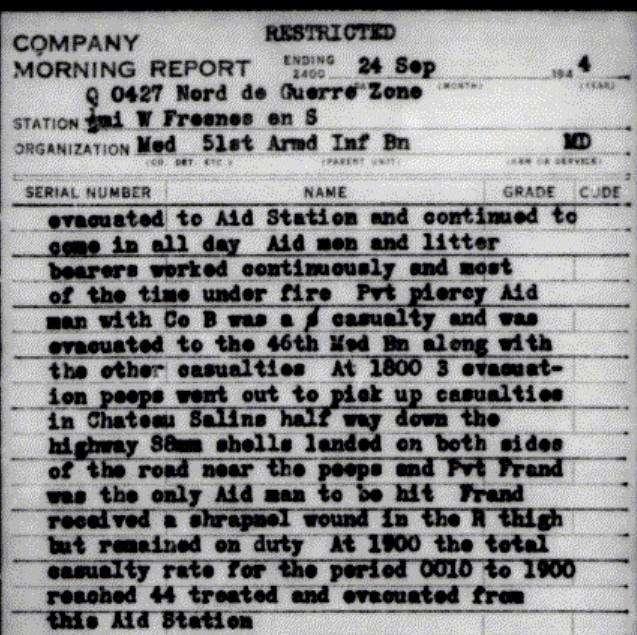

I can give you some examples to get an idea of the evacuees in the first echelon. I have chosen the reports for several days in November 1944: the 9th, the 15th, 16th and 17th. The morning reports of the medical detachment of the 51st Armored Infantry give us some interesting insights into the number and type of casualties evacuated to the battalion aid station.

What we can see is that often casualties from other units (of the combat command) were treated. We can also see that sometimes the casualties were evacuated to the Clearing Stations of other divisions. In this case, the Clearing Station of the 110th Medical Battalion (35th Infantry Division). This means that they will no show up in the records of the 46th AMB.

Look at the huge difference in the number of casualties between November 15 -16th and the 17th. I guess there was no such thing as a “routine day” for the medical detachments.

One final thing to note is the enormous medical burden that Combat Exhaustion and Trench Foot/ Frostbite caused by November 1944. I will cover these medical topics in future blogs in more detail.

Casualties in medical personnel

It is important to note that of all the casualties of the medical personnel in the 4th Armored Division, litter bearers are the biggest group (26 KIA; 40 WIA; 8 MIA and 54 SLD), not the company aid men/ surgical technicians.

Working close to the front line, with a job demanding that you move back and forth even when under fire, we can see why so many were hurt. Hurt by either artillery or mortar fire, or by the enormous stress of the job they had to do.

As one medic said: “Artillery and mortars don’t know the difference between a rifleman and a guy with a red cross brassard on his arm.” (Medical Service in the European Theater of Operations, Page 372)

Just like the red cross Brassard didn’t guard against artillery shells, it surely didn’t provide any protection against the psychological burden these heroes had to endure.

Conclusion

The General Board on evacuation concluded in 1945:

I believe the first sentence in the conclusion says it all.

They deserve our deepest gratitude and respect for their service and their sacrifice.

Pingback: Medical Evacuation and Treatment Series. Part 4: Battalion Aid Station. - Patton's Best Medics

Pingback: Silence - Patton's Best Medics

Hi, on 26 March 1945, Task Force Baum started at Aschaffenburg to liberate a POW Camp behind the lines at Hammelburg. We assume a M-29 with two Medics from CCB or 37 Tank Battalion was deployed. Any information to clarify this research issue is highly appreciated.

Best regards

Peter Domes

Hi Peter,

I will see what I can find on the medics and their vehicles. When I find anything of interest to you, I will let you know.

Reinier