First echelon evacuation meant getting the casualties away from the front line, as quickly as the tactical situation allowed, to a battalion aid station. Here, they would be seen by a doctor for the first time after being wounded.

“Soon after dawn, we began to receive casualties, many of whom were severely wounded. The aid men assigned to the station and I checked the dressings on the less severely wounded and gave them tetanus shots. We painted red Ts on their foreheads to let those in the rear know the shots had been given. We gave out a good deal of morphine and cigarettes, and we got these men out fast. We used the needle on the end of the syrette, a little tube-like a toothpaste tube, to fasten the device to the wounded man’s clothing to show we had given morphine. Our major objective was to get them to the rear before they were wounded again.

I assigned myself to the more severely wounded, making every effort to control major bleeding and starting plasma often. That was not always easy. I learned to use the femoral vein, which is deep in the groin, but larger than those in the extremities. It is not that easy to hit under those conditions.

Suddenly, there was a whistling sound followed very shortly by an explosion toward the rear of our field. It was my first experience with a mortar directed at us. Then there was a series of explosions much closer. Following my instinct, I dove for cover behind the forward hedgerow, as did most of the men who could move, and was soon covered with dirt and rock from the explosions. I suspect that because of the activity in our aid station, the Germans thought our station was a command post. They still seemed to respect our red crosses in the open. That this attack was made in error did not help us.

Then our heavy mortars seemed to get the range and began returning fire. Then it was quiet. I looked around. Everyone was covered with dirt. But there, standing, was one of my privates holding a bottle of plasma in his hand as the line went into a man lying on a litter near him.

That sight changed my life. I was embarrassed by not having attended to the wounded during the barrage by the example the private had set. Somewhere deep in my mind, I decided that such a thing would never happen again.

I made rounds. Some of the wounded had sustained new wounds. It was impossible to clean them adequately. we used up all our water trying to irrigate. We used up most of our bandages. We loaded the wounded onto jeeps as fast as possible and even persuaded an ambulance driver to come closer to our station where we could load wounded more easily. We instructed our drivers to return with more of everything. The amazing thing was that no one had been killed. Only one aid man was injured enough to require evacuation.

At this point, one of the men said to me, “Lieutenant, you have blood all over your pants.” I thought it was from one of the wounded, but then I noted a tear in my pants and then a superficial slash in my thigh. I did not remember being hit, and it was only then that I began to have some pain. I gave myself a tetanus shot. to clean this wound and to put a small bandage on it.” Combat Medic World War II, John A. Kerner, M.D. (page 62-63)

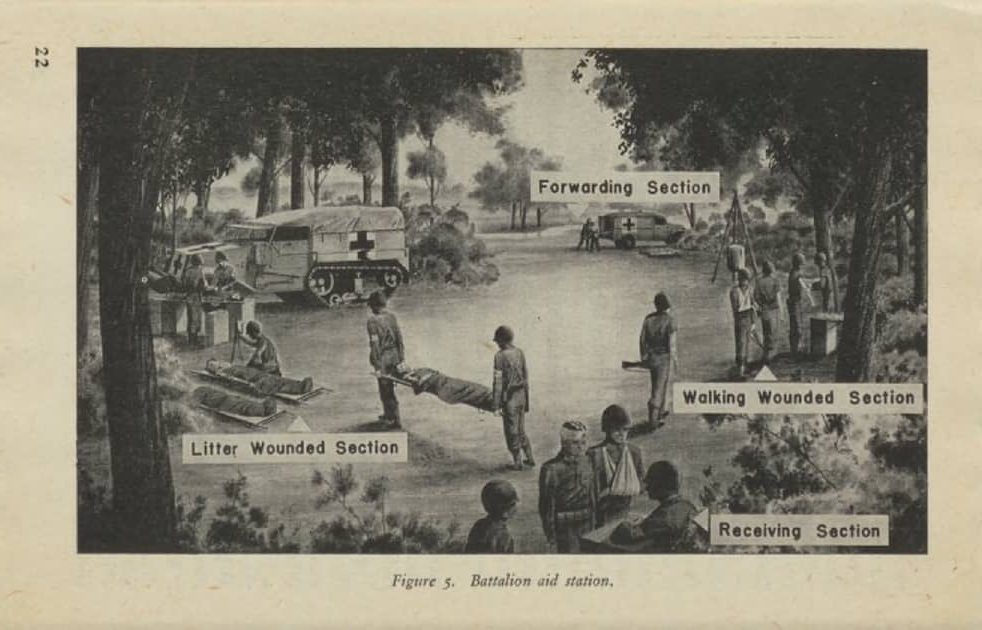

BATTALION AID STATION/ CASUALTY COLLECTING POINT

In an armored division, battalion aid stations were not always set up during offensive operations. The speed of advance often made it impracticable to unload all the equipment, set up a complete aid station, and then pack it all again to move forward as the advance continued. This was especially true for the medical detachments of the tank battalions.

When no aid station was set up, the casualties were evacuated to so-called casualty collecting points.

Collecting points were established along the axis of advance/ evacuation. The medical detachment sometimes placed a surgical technician at the collecting point to give basic care to the casualties. The rest of the medical detachment continued to follow the advancing troops they supported.

As Tracy Shilcutt wrote in her book Infantry Combat Medics in Europe, 1944-1945 (page 71):

“…; in essence, the BAS [battalion aid station] was not a physical entity, rather it was the medics and the care they gave.”

At the battalion aid stations/ casualty collecting points, casualties awaited further evacuation by the collecting platoons of the medical company (starting the second echelon in the evacuation chain). Tentative locations of the collecting points were discussed by the battalion surgeon with the medical company commander before operations. Sometimes it was then decided that the collecting points would be manned by personnel from the medical company (collecting platoon). This left more men of the medical detachment available for first-echelon medical care.

LOCATIONS

“On our next move, I set up my aid station in the back of a partially ruined stone barn, making a crude shelter out of two pup tents. This measure was necessary to keep us and the wounded out of the rain, which seemed ever-present, and it also provided an area that could be blacked out at night. It was a sturdy barn and quite a large one. In this location, though close to the front, we were sheltered from direct fire, and were unlikely to be hit by mortar shells. There also was a road leading to the rear. It was not much of a road, being unpaved, but it led to our collecting station about a thousand yards farther to the rear.

It was important for the shelter to be light proof because German planes came over at night.” Combat Medic World War II, John A. Kerner, M.D.(Page 72)

Preferred locations for collecting points/ aid stations provided shelter from enemy activity and the elements and easy access. They had to be set up close to the front to prevent long evacuation distances. So locations under trees, behind a hedgerow, or even in a ditch would be chosen.

When possible, especially during the fall and winter, a building was chosen for the aid station. Even when this meant a longer evacuation distance from the front.

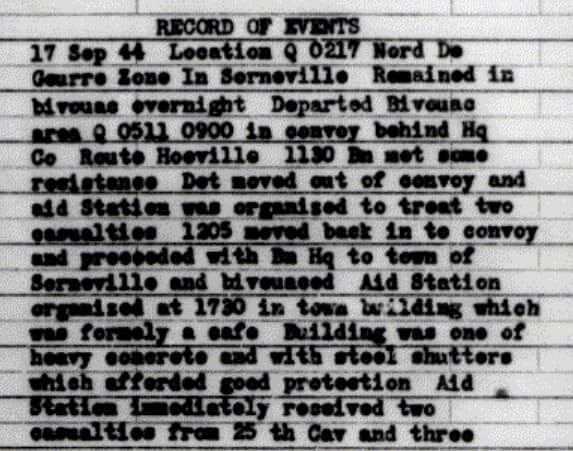

MD/51 Sept 17, 1944:

For a good impression of a battalion aid station, I encourage you to read this LIFE magazine article.

It follows the evacuation of one casualty, George Lott. He was a medic, serving in the 35th Infantry Division. This division fought alongside the 4th Armored Division in the fall of 1944. If you are interested in the follow-up article on George Lott, you can click on these links:

Ralph Morse, photographer tells the story of George Lott.

Or you can watch this video of an aid station/ collecting point set up in Troyes, France, by medics of the 4th Armored Division.

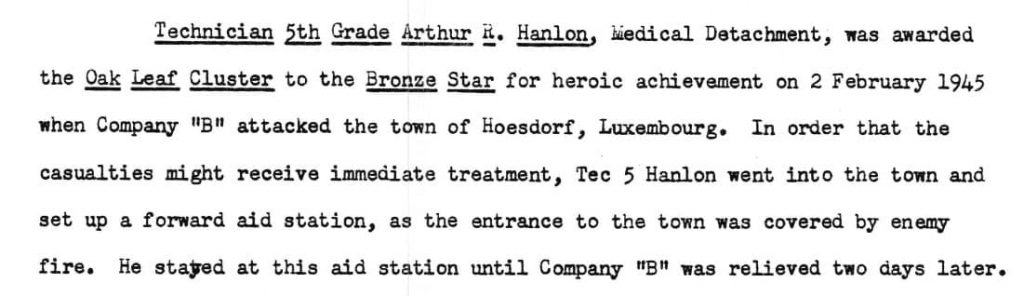

When a battalion aid station was set up and the distance to the front line became too great for effective medical service, it needed to move forward. But when no adequate new location was available (especially during the winter months, when the weather forced the aid stations to be set up in buildings), or when the tactical situation did not permit the movement of the aid station, medics sometimes set up a “sub-aid station” or “forward aid station”. This was a location, closer to the front, with one or two medics and some medical supplies, ready to receive a limited number of wounded as a stopgap measure between the company aid men and the battalion aid station.

SERVING DIFFERENT UNITS

“After the hedgerows, we were moving, moving, and moving. My aid men began to realize that any port in a storm would do and they did not hesitate to take our casualties to another aid station to get care for the guys they couldn’t get back to us. We took care of other units’ casualties in return. We became more resigned to the fact that even if it looked impossible, somehow or other we’d get our casualties back to safety and care.” To Hell With the Germans! Drive on, Garrison!-Dr. Richard R. Buchanan, M.D., Battalion Surgeon 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

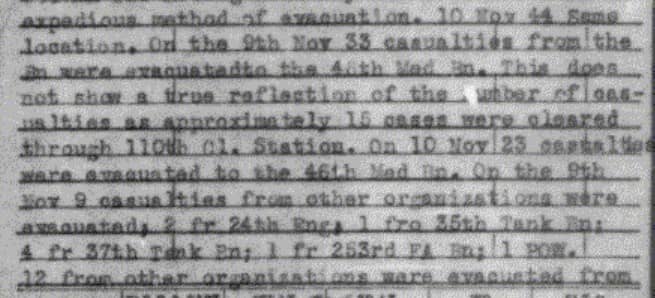

Often a tank battalion and an armored infantry battalion operated closely together, as part of task forces within a combat command. This meant that the battalion aid station of the tank battalion supported one of the task forces and the battalion aid station of the armored infantry battalion supported the other task force. Also, the companies of the armored engineer battalion, the ordnance maintenance battalion, and the troops of the cavalry reconnaissance squadron were attached to the different combat commands at a significant distance from each other. This made evacuation to the battalion aid station of their own medical detachment impossible. The combat command surgeon arranged the necessary medical support through the battalion surgeons of the tank or infantry battalions in his combat command.

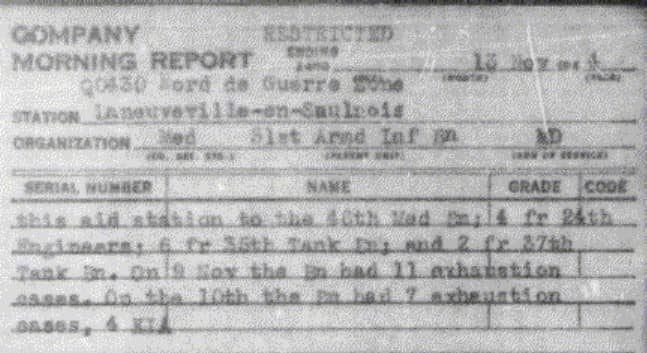

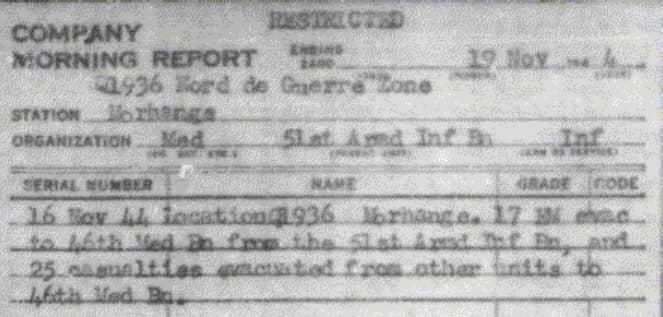

We can see this in the reported casualties of different units treated in the 51st AIB battalion aid station as reported on November 9th and 16th 1944, for example.

EQUIPMENT

“It is necessary to hang plasma bottles above the patient that gravity will cause the bottle to drain. We had to use various makeshift supports. Often we put a bayonet on a rifle, pushed the bayonet into the ground, and attached the plasma to the butt of the rifle. Occasionally, I would pump to make the plasma flow more rapidly as we tried to overcome shock.” Combat Medic World War II, John A. Kerner, M.D. (Page 72)

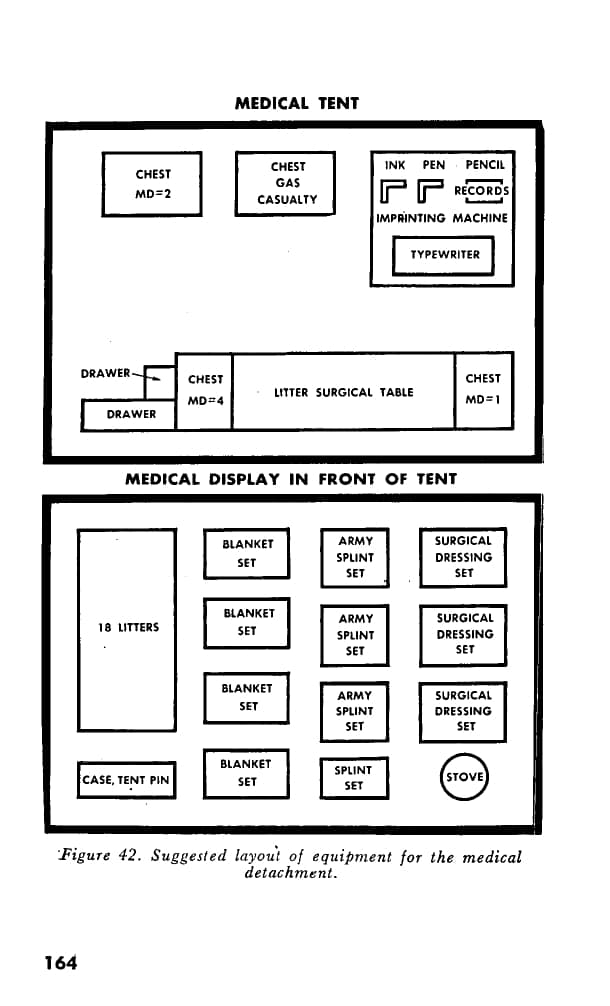

The equipment of the battalion aid stations in the different medical detachments was roughly the same.

There were three medical chests, carrying most of the medical equipment and supplies: Medical Chest no.1: Surgical Dressings, Medical Chest no.2: Drugs and Instruments, and Medical Chest no.4: Office Equipment.

The medical detachments of the armored engineer battalion and the armored infantry battalions also had the Medical Chest no. 60: Dental Field Equipment in their TO&E, since they had a dental surgeon in their team (for the first months of combat).

For a full list of the contents of these chests, click on this link.

Besides the medical chests, the equipment consisted of blanket sets, splint sets, gas casualty set, litters, and a Tent, Command Post.

It was all transported in a Dodge WC, 3/4-ton truck.

This photo shows the WC 3/4-ton truck of the 35th Tank Battalion Medical Detachment. Note the added brackets on the side. The litters were carried in these brackets.

Looking at the equipment list, we can see what the main focuses of the treatment in the battalion aid station were. As Tracy Shilcutt wrote in her book Infantry Combat Medics in Europe, 1944-1945 (page 69-70):

“BAS [battalion aid station] medics directed care toward impeding any further deterioration of the casualty’s condition, so that the wounded man could make the trip to the rear successfully. They accomplished this principally by following up on the initial care provided by the front line aid man: limiting blood loss with bandages and tourniquets, controlling shock with plasma, relieving pain with morphine, limiting infection with sulfanilamide, and immobilizing fractures and breaks.”

Only the very lightly wounded would receive their full medical treatment in the battalion aid station. All the other wounded were there only for as long as it took to stabilize their medical situation and for the collecting platoon of the supporting medical company to evacuate them.

PERSONNEL

“Sergeant Antel! He was my first sergeant. He was the backbone of my enlisted men’s strength in that detachment.”…” I had a lot of remarkable men in my outfit.” To Hell With the Germans! Drive on, Garrison!-Dr. Richard R. Buchanan, M.D., Battalion Surgeon 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

The team in the battalion aid station consisted of two or three officers and a group of enlisted. In Medical Detachments personnel, I have created a list of the personnel of the medical detachments, showing their role.

ENLISTED MEN

The team of enlisted men consisted of a variety of men, both in the number of men (4 enlisted men in an armored field artillery battalion, up to 22 enlisted men in an armored infantry battalion) and in their specialty.

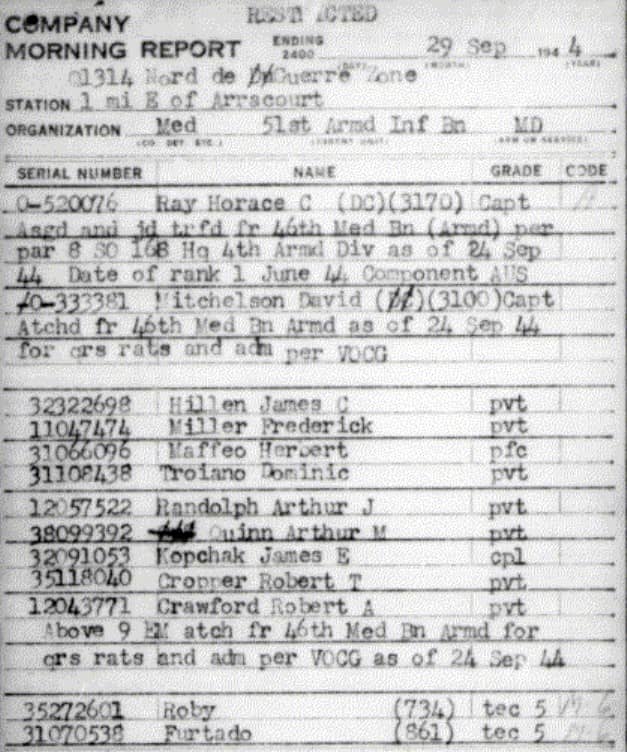

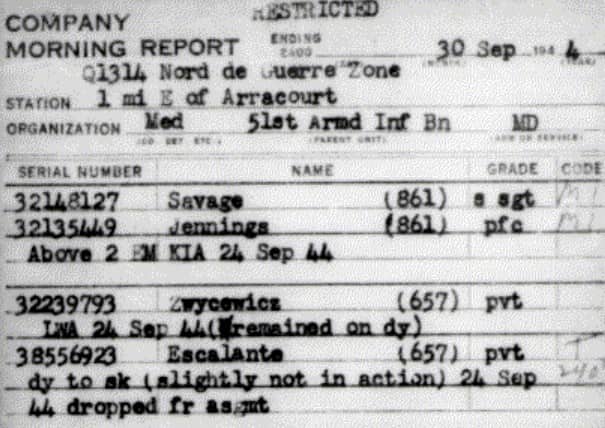

There were different technicians: surgical (MOS 861), medical (MOS 409), and sometimes dental (MOS 855). You can read more about their training in part 2 of this series.

There were litter bearers (MOS 657) (part 3 of this series) and Privates, Basic (MOS 521).

I have created a MOS List used in the medical units, where you can find out more about them. For more information, you can also read my blog on MOS.

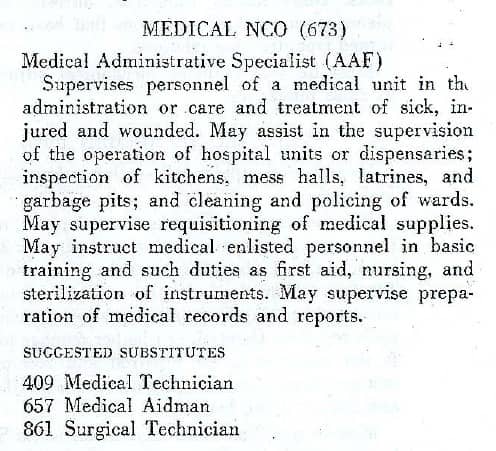

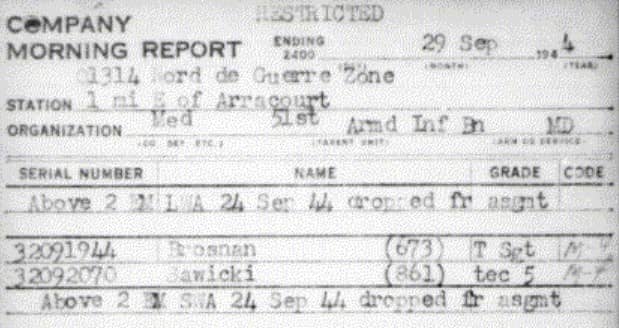

Every medical detachment had a Staff Sergeant, and Corporal, Medical NCO (MOS 673).

FM 12-427 Classification of Military Occupational Specalties of Enlisted Men, describes them as follows:

In many respects, they were the backbone of the unit. They took care of most of the administrative work, supervised the team of enlisted men, were trained to assist the officers in emergency medical treatment, and could even replace them when necessary.

OFFICERS

The officers were: the battalion surgeon, the assistant battalion surgeon, and in the armored infantry battalions and the armored engineer battalion, a dental surgeon. In the armored engineer battalion, the dental surgeon was the assistant battalion surgeon, as this medical detachment had no other officer assigned.

Dental surgeon

To start with the latter: the 4th Armored Division found that dental surgeons working in battalion aid station were unable to do their jobs properly, due mostly to the rapid advances of the division.

Division Surgeon Journal 26th August 1944:

It was therefore decided to bring the dental surgeons from the medical detachments to the clearing stations of the medical companies.

Division Surgeon Journal 22nd November, 5th December, and 18th December 1944:

With the dental surgeons, the dental technicians, and the Medical Chests no. 60 were reassigned to the clearing stations of the medical companies.

The assistant battalion surgeon

The assistant battalion surgeons were Medical Corps or Dental Corps officers, depending on the medical detachment’s TO&E. In August 1944 they were gradually replaced by Medical Administrative Corps officers. The idea behind this replacement was that this would increase the number of available replacement doctors.

Division Surgeon Journal 20th , and 24th August 1944:

The mentioned training of the MAC assistant battalion surgeons was:

“The 6-week course for battalion surgeon’s assistants focused on subjects that would qualify a nonprofessional lieutenant in the Medical Administrative Corps to assume responsibility for a battalion aid station and assist the battalion surgeon in the treatment of casualties. A total of 140 hours of training time, or almost half of the scheduled 300 hours of instruction, were devoted to subjects related to field medicine and surgery, including emergency medical treatment, treatment of chemical casualties, transfusions, chemotherapy, and use of penicillin. Fifty hours were devoted to the tactical use of battalion aid stations in the attack and retrograde movements, and 42 hours were devoted to field sanitation. The balance of the time was allotted to administration and military training. Two weeks of the course were spent in field exercises.” Medical Training in World War II page 124.

The MAC assistant battalion surgeons were tasked with most administrative tasks (including directing the ambulance litter team) and he treated the lightly wounded. He was assisted by the Medical NCO Corporal (MOS 673).

Division Surgeon Journal 9th September 1944:

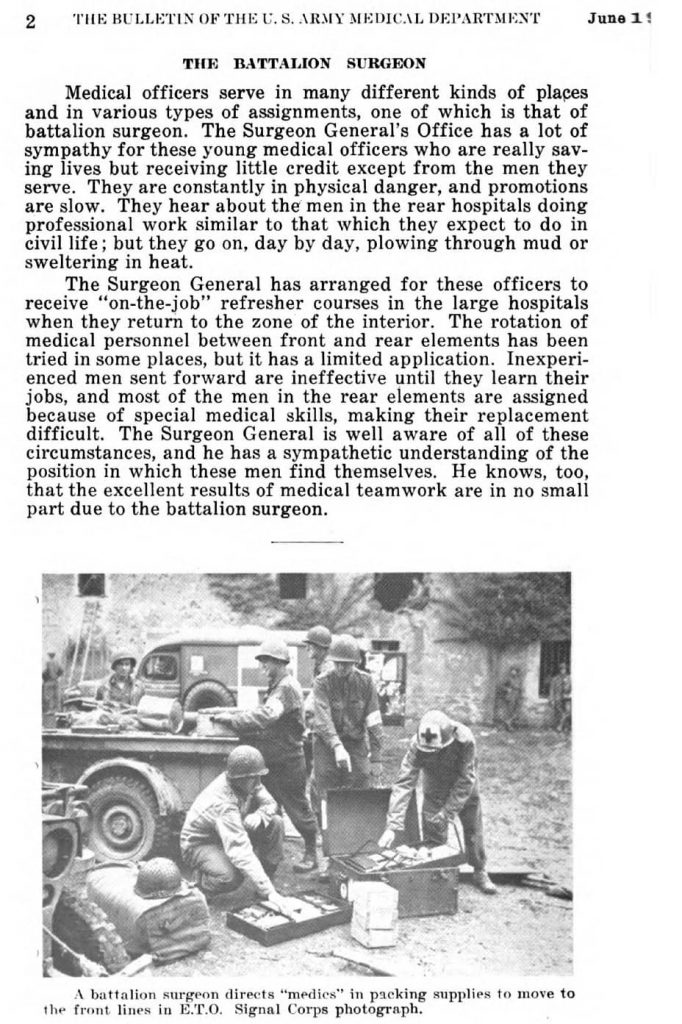

The battalion surgeon

“The battalion medical officer’s responsibilities make demands upon his previous training but these differ widely from his past experience. He most certainly has never before been suddenly confronted with a half gross or more of injuries running the gamut of head, chest, abdomen, and extremities, nor has he ever before worked to the limit of his physical and mental capacities where all about him are chaos and confusion”. The Army Medical Bulletin, Volume 61, April 1942, page 119.

These doctors had often graduated from medical school in an accelerated program, aimed at graduating doctors quickly for the armed forces. They were accepted in the Army with one year of internship as practical experience. They were then sent to the front after a 6 weeks Medical Field Service School course at Carlisle Barracks, Pa. This course focused mostly on military organization and administration.

Brendan Phibbs, in his book The Other Side of Time, a Combat Surgeon in World War II , describes a few scenes from his training at Carlisle Barracks:

“Over beers in the Molly Pitcher Bar ten days out in training: “I wonder if it’s occurred to anybody else these guys don’t know what the fuck they’re doing? “ “I spent three hours last night drawing up march tables for a horse-drawn column, for chrissakes!” “It’s 1864 and we got all these horses, see. On to Richmond!” “I mean, this is no shit, you guys. I’ve never been in a war before….” “Neither have these guys.” “Well, there must be a hell of a lot of stuff we ought to be learning about battle casualties and high-velocity wounds and evacuating people and logistics. When the hell are we going to learn something we can use? “ “Matter of fact, I’m not sure what it is we’re going to be doing. Is anybody? ”

“Don’t ask me; so far I’ve learned how you hold your hand you salute and who ranks who in the army general staff and how I shouldn’t catch VD.” “Tell you what we’ll do. We’ll ask Snout. Snout’s our man.”

The tables roared. We already had an enemy, a buffoon, and we had named him Colonel Snout. Like most medical administrative corps officers who are commissioned to help doctors run the medical corps, he hated physicians, and to this unpromising substrate he added a dense mind, a small soul, and a galloping insecurity that twisted his face in grotesqueries with the effort of conveying the time of day. We already had a collection of Snoutisms, and we were shouting them around the room when a couple of us saw Snout’s long nose and close-set eyes rising like an evil moon over a booth. With nudges and kicks we conveyed the situation. Snout had a silent audience.

“Want to know what it is you’re going to be doing?”

The voice had a British precision, and a feminine delicacy.

“Come to class Wednesday, gentlemen. I’m going to tell you all about it. Ten hundred hours.”

At ten hundred hours on Wednesday, Snout for once faced a room full of attentive, concentrated faces. We muttered, surprised, apprehensive, that the son of a bitch really looked happy; and so he did, or as nearly as he was capable of it, standing there on the platform, leaning on fingertips; his face had stopped drawing itself into exaggerations. He began gently.

“The field medical service, gentlemen,” sonorous, long pause.

First Snout guessed he’d better tell us just what the field medical service was not.

A series of slides showed us where we were not going. Lowry Air Force Base Hospital in Denver, Walter Reed Hospital in Washington, assorted hospitals in London and Noumea, various university medical school units, hospitals under tents in places like Australia, field surgical units (M.A.S.H. in later wars). Snout showed us pictures of green, remote Cockaigne, where physicians worked as physicians, where young doctors could pick up unparalleled experience in reasonable comfort and safety and even in ease, where there were, by inference, nurses to screw and booze to drink. Not, we gathered, by us.

Snout swelled his chest and struck a pose. “Now the field medical service. Next slide, Corporal.”

We started with the medical support of the “fighting units, the divisions,” from the rear forward. We noticed a clearing’ company under tents several miles behind the lines. Here the wounded would be stabilized, hemorrhages checked, splints and plaster applied to fractures; there would be sorting and evacuation. The clearing company would be out of range of anything except heavy artillery. Dull, no significant definitive medicine or surgery practiced, but at least safe.

We were taken the next step forward to the collecting company, again under canvas, maybe in a building a mile or two from the front. This, we learned, was the first level of real medical care the wounded would encounter, the first chance to immobilize torn tissues, treat shock and hemorrhage, and sort the casualties in terms of severity, Here we would be in range of medium artillery and, of course, planes. The collecting company should be sited with great care for maximum shelter and protection for the wounded.

“NOW, Corporal’ —Snout really yelled it. The slides went off and the corporal pulled the curtain from the wall behind Snout; on the wall was a huge mural on panels of plasterboard, obviously a standard prop. The mural showed a first lieutenant, medical corps, wearing a helmet with red crosses on it; he was crouching in a shallow depression in the field with two aid men doing something to a bloody casualty. Shells were lifting the earth in shreds of a few yards away, soldiers were running in the distance.

“BATTALION AID! THE REAL ARMY! “Snout dropped his voice from ululation to low-sinister and for the first time in a Snout lecture, I began taking notes.

“Every fighting battalion—infantry, artillery, tanks—will have a battalion surgeon. The surgeon marches with that battalion, sleeps in the mud and snow with it, suffers fire and hardship with it. He commands some thirty medical soldiers who work in the aid station or march as company aid

men, right among the riflemen and gunners. The battalion surgeon will set up the aid station in the first available defilade. You may remember, gentlemen, that defilade means a place out of the line of direct fire of machine guns and small arms. It means in the first ditch or wall or depression in the ground you can find. You are going to spend your professional lives within a few hundred yards of the enemy and you’d better learn to dig holes quickly and deeply if you want to live long enough to be promoted. Artillery, mortars, patrols, cold, wet, mud, snow, and misery; these, gentlemen, are the facts of life in battalion aid.” Silence.

“Ha, ha, ha.” The noise came out of Snout. The face didn’t go with any sound of ‘ha” I’d ever heard.

We were going to be real soldiers out there, we heard. We were going to be part of a fighting battalion, and there wouldn’t be any prancing around operating rooms being a bunch of civilians in disguise the way most of the goddamn doctors were when they came in the army. No sir. We’d better pay attention to what we were being taught if we expected to live.

“Doctors!” Snout laughed. We were going to be up there for morale, we heard, and that was all. We weren’t going to be functioning as physicians; we’d be glorified aid men.

At the back of the room the commanding colonel coughed. Snout shook himself out of his euphoria and toned everything down. Of course, that was just the way some people put it. We were really going to be physicians—this with a cynical grin—it was just that we were going to find ourselves in some extremely difficult and challenging surroundings that would call for the best in courage and initiative…

The class, for once, was still: the facts of military life grinned out of the colonel’s cartoon, and they didn’t resemble anything we had imagined.

That night, in bars and barracks we calculated our chances like condemned men drawing straws: who among us would be the poor sods assigned to some infantry battalion? I listened, I nodded, I discussed benign alternatives, but a small voice told me I’d seen my future on plasterboard: throughout the rest of a month of marching and drilling and sleeping through frivolous lectures that mural exploded and flamed and I knew against all the comforting odds that that was exactly where I was going.”

The negative connotation that the duty of battalion surgeon had among physicians, was not only due to the danger and hardships involved. Many physicians felt that serving as battalion surgeon was bad for a post-war career because the wartime experiences would not be seen as relevant for a career in civilian life:

“There exists the notion among young medical graduates that an appointment to operative surgical teams and to base hospitals offers opportunities to gain vast experience in chosen specialties, whereas being assigned as a battalion medical officer engenders atrophy of previous knowledge and experience. This is absurdly wrong”. The Army Medical Bulletin, Volume 61, April 1942, page 120.

This article in The Army Medical Bulletin, acknowledging the difficulties and hardships of the duty, sometimes reads like an advertorial for battalion surgeons:

“The officer who feels that his professional talent will be wasted as a battalion surgeon simply hasn’t been there.” (Page 122)

“Among medical veterans the expression is common that if they go again they want to serve with the troops, and it is not only the excitement but the actual professional responsibility which intrigues them”. (page 123)

In June 1945, the Surgeon General did acknowledge that there was some truth to the fear of the battalion surgeons. He started “refresher courses” in large hospitals for battalion surgeons returning after the war.

Bulletin Army Medical Dept. June 1945:

The medical skills and judgments of the battalion surgeons were truly the foundation of the medical service in the Army. On his shoulders rested the responsibilities of life-saving treatment with very limited equipment and supplies, and the often counterintuitive decision to stop or even withhold treatment of those casualties deemed “hopeless”.

“He must learn under trying conditions of active combat to recognize the doomed patients and to exercise that same calm impartiality shown by the judiciary when they pass sentence.” The Army Medical Bulletin, Volume 61, April 1942, page 121.

And all of this in makeshift facilities, amidst the chaos and thunder of war.

Besides the medical duties, the battalion surgeon was also a staff officer in the battalion staff. His duty was to develop the medical plan for the battalion commander, keep him informed, and advise him on all medical matters concerning the battalion. This included advising locations for the battalion aid station. He was also responsible for liaison with the next higher echelon (the medical company) to ensure rapid evacuation and resupply of the medical detachment.

The third duty of the battalion surgeon was the command of the medical detachment. In this duty, he was assisted by his assistant battalion surgeon and the medical NCOs, but ultimately, the well-being, training, and functioning of the entire team was his responsibility.

“I had to go forward and visit my medics in B Company who were having a Hell of a time. They were running on pure nerve. Their adrenaline was wearing out, so they needed some encouragement. They were all doing very good work and deserved to be told.” To Hell With the Germans! Drive on, Garrison!-Dr. Richard R. Buchanan, M.D., Battalion Surgeon 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

In the same article doctor Buchanan describes his own experience when his “adrenaline was wearing out”:

“I remembered another time I cried, after the bombardment of Lunéville. We had evacuated all the casualties, we had done our job as best we knew how, we were evacuating the area, we were moving out in the dark with the battalion to Arracourt to face the German tanks. All of a sudden I began to sob. In between sobs I said, “Now, men! I’m not going combat-fatigued! I’m all right!” I got it out of my system and that was that. It was tension. It was so horrible. I hate to even mention it.

We were so tired and finally the column stopped and they said, “Okay, we’re gonna be here for a couple of hours.” We just laid down there on the ground. We were there for more than a couple of hours because when we woke up it was dawn. I looked at myself and I was soaked with blood from my elbows all the way down. I hadn’t washed off the blood of the wounded. I didn’t even know it was there!” To Hell With the Germans! Drive on, Garrison!-Dr. Richard R. Buchanan, M.D., Battalion Surgeon 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

Doctor Buchanan somehow managed to keep going. For many who worked in the battalion aid station, this became impossible. By wounds, either visible or invisible, they became casualties.

“Our medical clerk, Corporal Morelli, developed a case of combat fatigue right under my nose. We got caught in a surprise artillery attack. We had no time to seek foxholes. Morelli and I dove under the medical trailer. As the shells landed and burst, a fragment hit the tire just above my head. There was this loud hissing sound. Morelli shouted into my ear, “Captain, I’m hit! I’ve been shot!” I yelled back, “Bleep-bleep it Morelli! You’re not hit! That’s just the bleeping tire going down!” But Morelli had had it, and he was no good from then on. We evacuated him. He never came back. He was assigned as a clerk/typist to a unit in the rear.” To Hell With the Germans! Drive on, Garrison!-Dr. Richard R. Buchanan, M.D., Battalion Surgeon 704th Tank Destroyer Battalion.

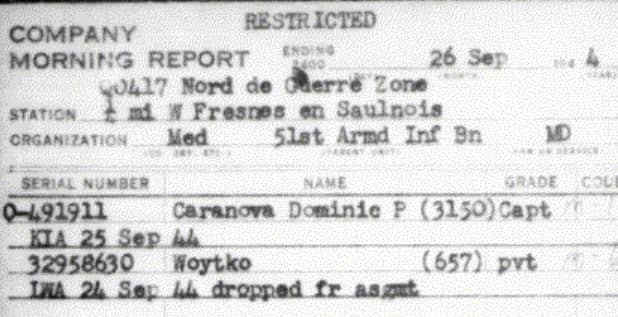

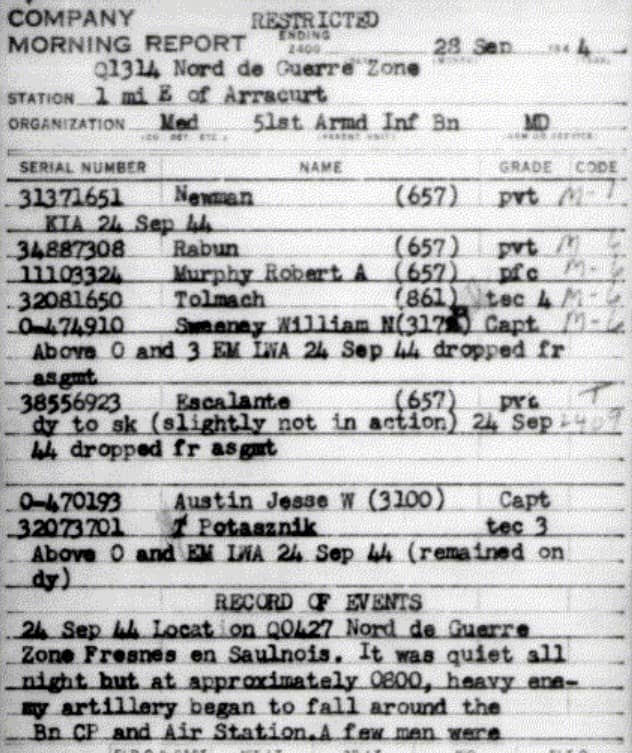

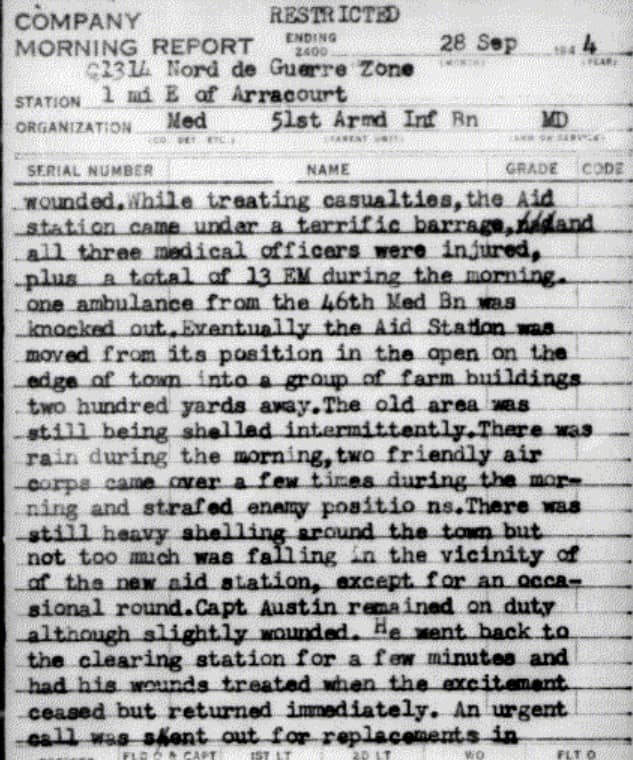

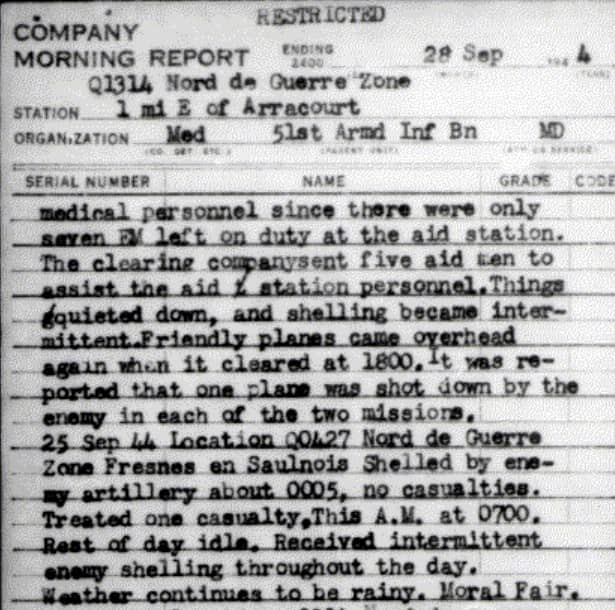

The most extreme example of this, that I found in my research happened to the medical detachment of the 51st Armored Infantry Battalion, on 24th September 1944. An artillery barrage decimated the battalion aid station. Of the enlisted men, 10 had to be evacuated for wounds or combat exhaustion. Three enlisted men were killed in action. One later died of his wounds. All three officers were wounded. Two had to be evacuated for their wounds. Captain Caravona died of his wounds the next day. This left the aid station with only 7 enlisted men and one wounded officer, Captain Jesse Austin. After treating all the wounded in the aid station, Captain Austin went back to the nearest Clearing Station, to have his wounds treated. Then he returned immediately to resume his duty. The medical battalion rushed in reinforcements as soon as possible. And after all this, the morning report still states that “morale was fair”.

You can read the story here, in the Morning Reports. They show us what happened, who was wounded or killed, and who was send to replace the casualties. If you find them difficult to understand, please click on this link. It will show you my blog on Morning Reports.

I must admit that of all the different people I have studied in my research, the battalion surgeons have touched me the most. Being a physician, I have often thought about these men during my research.

I have tried to imagine what it must have been like to practice medicine like they had to. Would I have been able to do it? Would I have been able to keep going, or would I have cracked under that pressure?

I don’t know the answers, although I am afraid that the answers might very well be negative. I can only say that every time I think about them, I am extremely thankful that because of the freedom they and their men helped to restore, I have not been called upon to find out.

Pingback: Silence - Patton's Best Medics

Pingback: Trench foot and Frostbite epidemic in the ETO - Patton's Best Medics