“MEDIC!”…

I think we have all seen scenes in war movies or Tv-series where one of the portrayed soldiers is wounded in battle:

Men are running. There are disorienting loud noises: the rattling of machinegun fire, the “pings” of M-1 Garand clips ejecting. There are explosions. Orders are shouted. Then there is that scream: “MEDIC!”.

We see blood, we see fear. Someone starts to dust the wound with a white powder. Then something is forcefully struck in the wounded man’s skin.

A man with a red cross on his helmet arrives. He examines the wounded at a glance. A bandage is quickly applied. The wounded man is placed on a litter.

The camera turns back to the battle. End of scene.

I think that for most of us scenes like this have shaped the image we have of the medical treatment and evacuation during WW2.

What I would like to do in this series is to take a closer look at this image that we have. Is it accurate or do we need to change our image? And what was supposed to happen next, when the camera has moved on to the next scene?

In each part of this series, I will have a look at the different parts of the evacuation chain.

When a man was wounded, who would he meet during his treatment and evacuation? What were the roles of the men that would treat him? What was their training like? What equipment did they have with them?

So, let’s have an in-depth look at the medical treatment and evacuation of the US Army in WW2, and let’s reexamine the picture Hollywood gave us.

First aid

The first steps in treating a casualty were supposed to be taken by the casualty himself or his comrades. His comrades were only allowed to give first aid when it did not interfere with their combat duties (FM 21- 11, Section I, Paragraph 5).

A company aid man, the first medical department personnel a casualty would see when wounded, simply could not be everywhere at once. Often, due to heavy shelling, for instance, he could not reach a casualty for some time. It was vital that every soldier could start lifesaving treatment of any casualty in his unit.

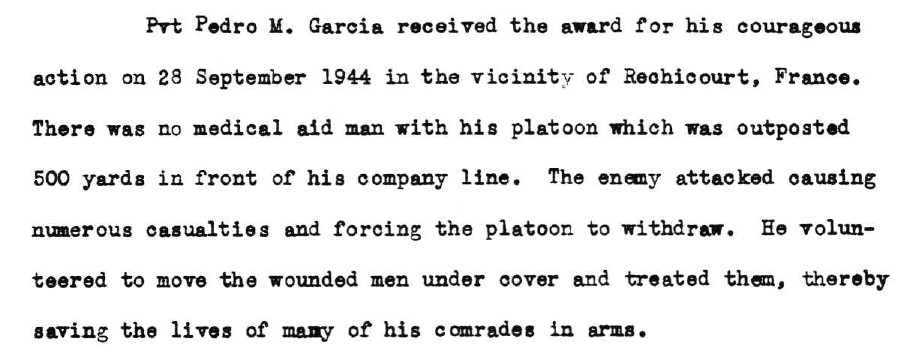

Many examples of soldiers giving first aid to comrades can be found in the various After Action Reports and Citations for medals.

Here is one example:

For situations where first aid was necessary every soldier had received a couple of hours of training during his basic training and he carried some first aid equipment.

Sometimes he had access to additional first aid equipment in the various motor vehicle first aid kits.

Soldiers in an armored division, with its 2,500 vehicles had better access to these vehicle kits than their infantry division counterparts.

First, let’s look at the first aid training.

Basic training

In Training of the American soldier during World War I and World War II, the author writes the following about the (infantry)training programs of the US Army:

“Initially, training was conducted in accordance with Mobilization Training Programs (MTPs) developed during the interwar years. Standardized Army Subject Schedules further detailed procedures and methods to be used for each subject taught. The second phase in the cycle was analysis and modification of the initial MTPs, partly as a result of experience in training, but more so in response to lessons learned in combat and comments from commanders in the field. The final phase of training was the development and refinement of final MTPs and Subject Schedules, incorporating the lessons learned from combat.“

“Upon initial mobilization in late 1940, individual training was provided primarily through Replacement Training Centers (RTCs). After the declaration of war, and full mobilization, individual training was provided within newly formed divisions. And finally, as the war progressed and the army neared its 90-division level, individual training began to shift back to the RTCs. It is important to understand the development of the RTCs and division training and their contributions to individual training. But, in both the RTCs and division training the specifics of individual training were primarily set forth in the MTPs and Subject Schedules and were similar in subjects taught and hours allotted in both RTCs and division individual training.” (Page 91-92).

In short, every soldier received his training, either in RTCs or within newly activated divisions. During the war, the specifics of this training were changed according to the lessons learned by the Army.

These changes also affected the training in first aid. This training took place in the first 4 to 5 weeks of basic training:

“The 13-week basic training phase was allotted to individual and small-unit training up to battalion level. With the MTP as a guide, this period was further divided into three phases. The first month concentrated on basic subjects such as military courtesy, discipline, sanitation, first aid, map reading, individual tactics, and drill. The premise was that the individual must first learn to be a soldier before learning a specialty.” (Page 100)

In the MTP published in October 1942, we find the number of hours allotted for first aid training.

“Military sanitation, first aid, and sex hygiene: 10” (Page 101).

But by 1943 the MTP was changed. It dramatically reduced the hours spent on first aid training:

“Military sanitation and first aid: 3” (Page 107).

To give an impression of this training I have taken the relevant pages from the Instructors’ Guide to MTP 8-1 (September 1942). This specific MTP was for the US Army Medical Department but gives us a general idea of the subjects discussed in all other MTPs. In the first weeks of basic training in this MTP 5 hours were allotted for Personal Hygiene and First Aid:

As the war progressed, the US Army found it needed to spend more time on the tactical training of its recruits. With the ever-present need for more and more replacements, it was not possible to lengthen the duration of basic training. So the allotted time for some subjects, including first aid, had to be reduced. This was far from ideal but an understandable choice, given the demands of the war.

The reduction in training time did have negative consequences on the quality of first aid given. Major V.P. Marran in his book Medic with Patton’s Third Army gives us an example of this:

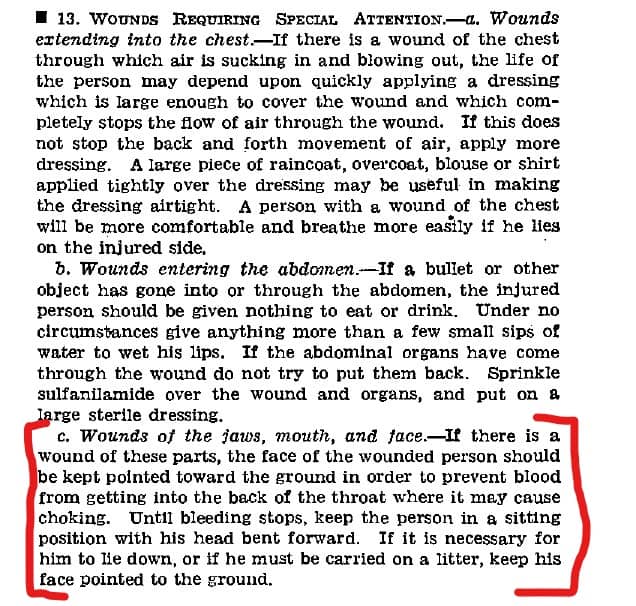

“We lost four men yesterday who should have made it”. “What happened? ” I responded. “During evacuation, one bled to death and three choked to death on their own blood and saliva.” He stopped and looked at me intently. “I’d say improper evacuation on their backs for the last three. Probably someone missed a bleeder and didn’t tie it off on the first one.”…..”They must be taught to understand that these cases have to be evacuated face down..” (Page 32)

As we can see that this topic was covered in the FM 21-11:

It was also covered in this training film (13:16 min).

With more time available on training situations like this might have been avoided.

After basic training

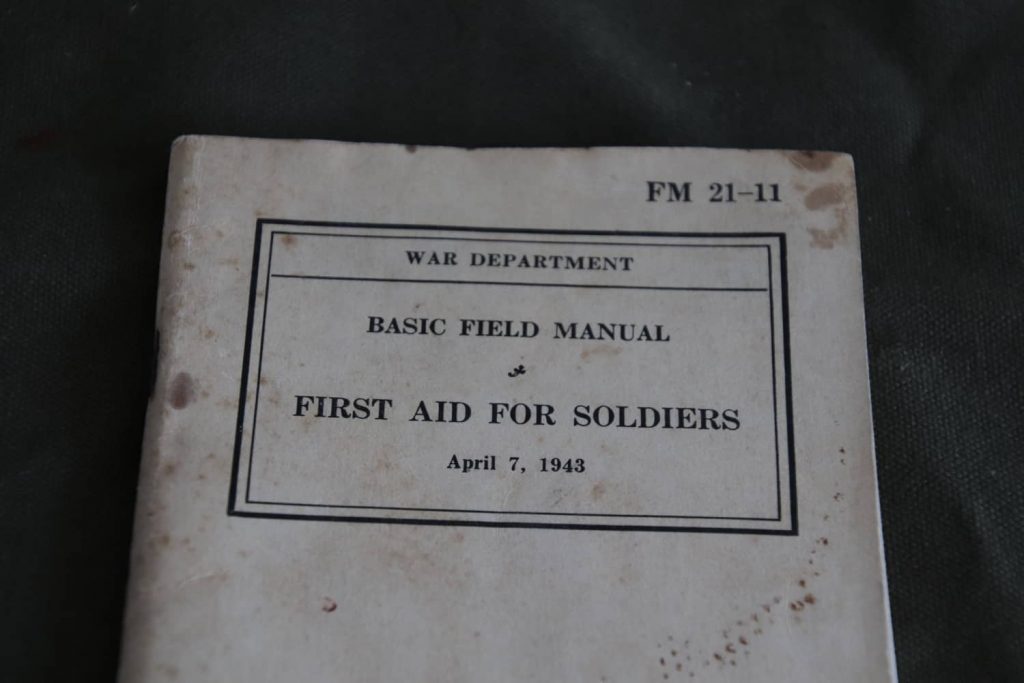

After basic training soldiers could refresh or increase their knowledge of first aid by reading the FM 21-100 Basic Field Manual- Soldiers Handbook chapter 14, section 2, and by reading FM 21-11 Basic Field Manual – First Aid for Soldiers.

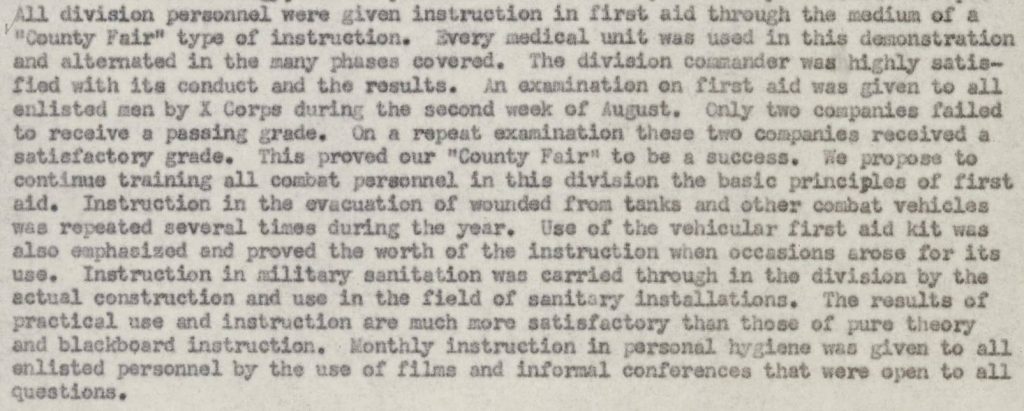

The 4th AD medical personnel developed a “country fair” type of first aid training in 1943. It was used to train all division personnel in first aid after basic training.

The personnel of the 4th AD was lucky. Since the division was activated in April 1941 and saw its first combat in July 1944, its personnel was allowed a long training period. Significantly longer than most divisions.

With this time came the opportunity to train all personnel in vital subjects such as first aid.

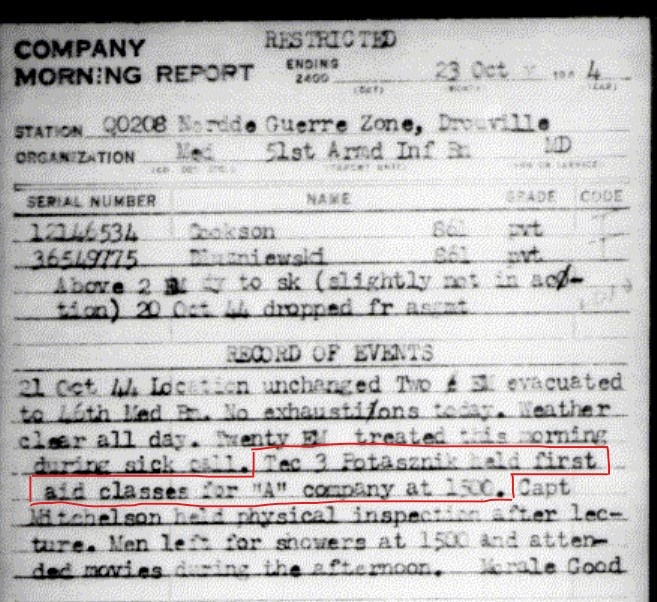

Also, in the 4th AD, the medical personnel spend the periods between combat operations organizing first aid lectures for (new) personnel of the division. With these lectures, it was hoped that the quality of first aid provided by and to the personnel of the division was at least adequate. Even with the many replacements.

First Aid Kits.

Now that we have taken a look at the training of the individual soldiers I will continue by having a look at all the different first aid kits available to the soldiers of the 4th AD (so I will not discuss the First Aid Kit Jungle, First Aid Kit Aeronautical, etc.). For more information, you can read Section XI of FM 21-11.

- Individual First Aid Kit:

Every soldier received a first aid kit. Is was located in a web pouch attached to his belt. The kit consisted of a First Aid Packet and a packet of Wound Tablets.

The First Aid Packet was a can that contained a wound dressing and an envelope with sulfanilamide powder. The powder was to be applied to a wound.

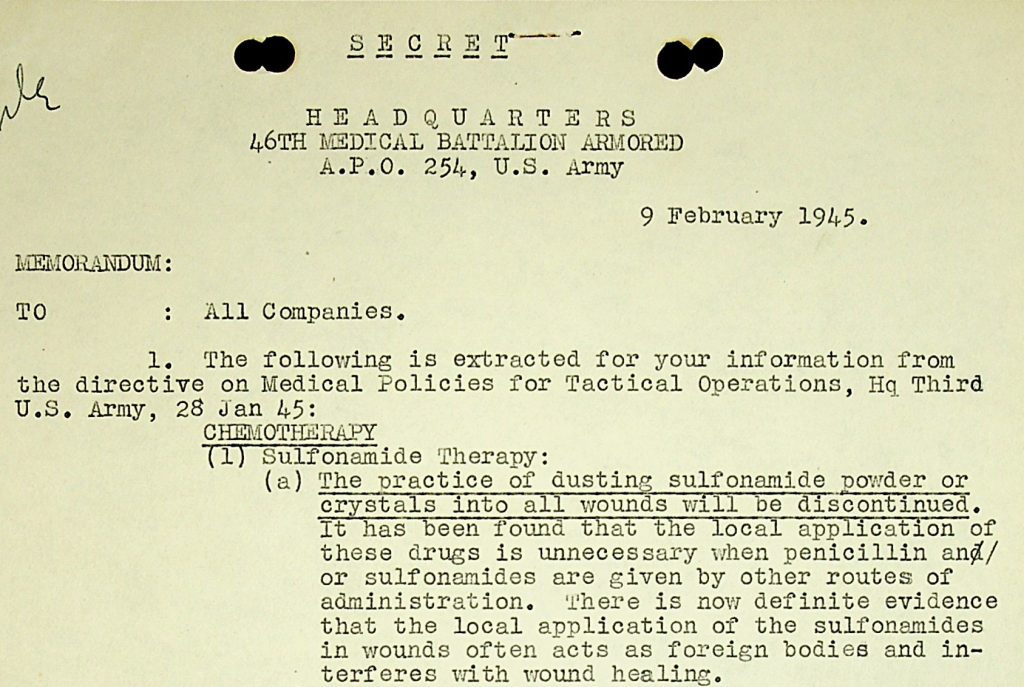

Research conducted during the war found that using this powder acted as a “foreign body” in the wound. It, therefore, hindered rather than helped a wound to heal. The troops received orders to stop the use of sulfa powder in February 1945:

For more information on these first aid packets: (https://www.med-dept.com/articles/history-development-of-the-carlisle-bandage/)

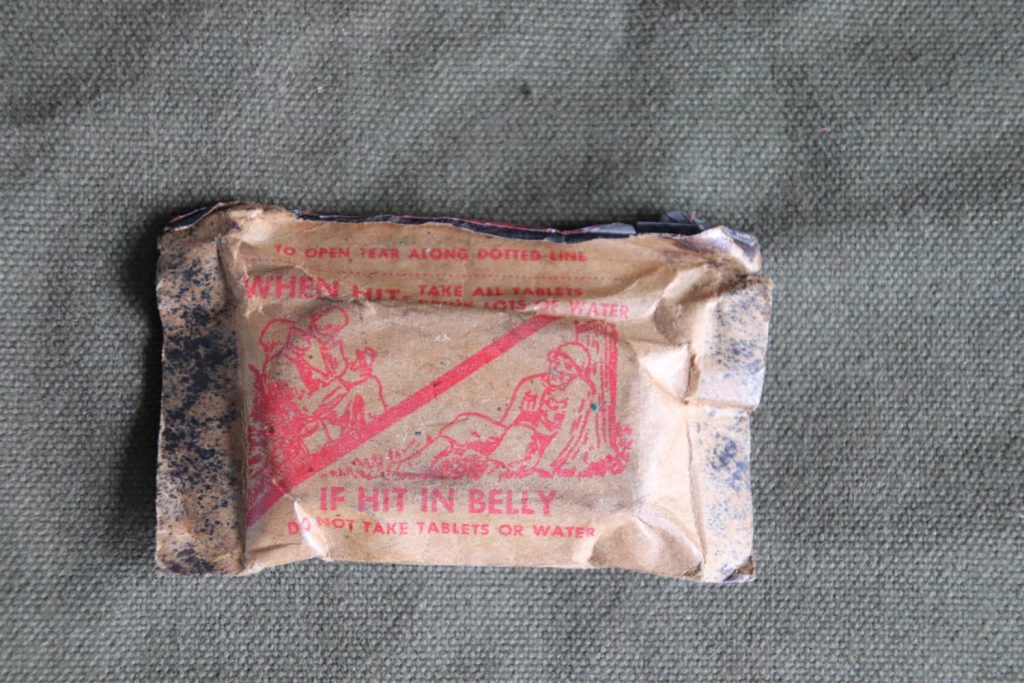

The Wound Tablets packet contained either 8 tablets sulfadiazine or 12 tablets sulfanilamide.

The most common side effect of these sulfa drugs was diarrhea. Instructions were therefore to take these tablets with large amounts of water when wounded (and not to take them at all when wounded in the abdomen).

The effect of quickly starting this antibacterial treatment was a decrease in infectious complications of battle wounds.

What was NOT part of an individual’s First Aid Kit was morphine. So when we are shown a scene where a soldier stabs a syrette of morphine into a wounded comrade’s limb it is Hollywood fiction. Individual infantry and armored soldiers simply did not carry morphine (morphine was a standard item in the airborne first aid kit. Presumably, this was done because paratroopers would probably be separated from their company aid men).

As a side note: to use a syrette, which looked a bit like a small toothpaste tube, soldiers had to: “remove transparent head of morphine syrette. Grasp wire loop and push wire in to pierce inner seal, turning if necessary”. “Pull out and discard wire, thrust needle through skin at least half its length, and inject solution by slowly squeezing syrette from the sealed end.”

So it was a more elaborate and delicate procedure then simply stabbing a needle in as we are so often shown.

The last item an individual carried for first aid was a tube of Protective Ointment (M-4) in their gas mask carrier. This ointment was to be used as first aid in case of exposure to chemical weapons.

- Vehicle First Aid Kit:

Besides the individual first aid kits soldiers carried on them, they could have access to motor vehicle first aid kits.

An armored division, with its 2,500 vehicles, had plenty of these first aid kits according to the Armored Division’s TO&Es.

For example, a tank company had 5 first aid kits, gas casualty (1 per 25 individuals) and 3 first aid kits, motor vehicle, 12-unit, and an armored infantry company had 7 first aid kits, gas casualty, and 12 first aid kits, motor vehicle, 12-unit.

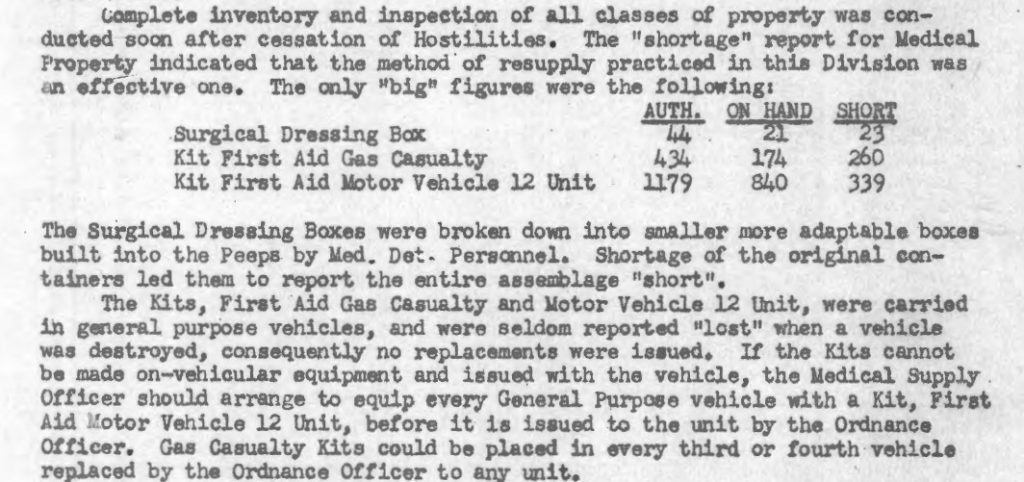

In the Supply Annex of the 46th Armored Medical Battalion’s Annual History 1945 we can see the totals authorized in the TO&Es:

MOTOR VEHICLE FIRST-AID KIT (12-UNIT):

This kit, supplied to motor vehicles, usually one to every fourth vehicle, contained:

- Burn injury set (boric acid ointment or 5 percent sulfadiazine ointment and wooden applicator) (2).

- Eye dressing set (1), consisting of-

- Two-inch eye pads.

- Double-strip adhesive plaster packets.

- Tube of boric acid ointment.

- Tube of butyn sulfate and metaphen ophthalmic ointment.

- Iodine swabs (1 package).

- Sulfanilamide (5 grams) in a sterile individual double-wrapped envelope with shaker top (6).

- Adhesive compresses, I by 3 inches (16).

- Bandage compress, 4 by 4 inches (1).

- Bandage compress, 2 by 2 inches (1).

- Gauze bandage, 4 inches by 6 yards (1).

- Triangular bandage (1).

- Tourniquet-scissors-forceps set (1).

- Ammonia inhalants (10).

- Safety pins (10).

- Morphine tartrate syrettes (1/2 grain) (may be added to this kit upon the direction of the commanding officer when the military circumstances indicate its need).

MOTOR VEHICLE FIRST-AID KIT (24 UNIT):

These kits were designed to be supplied to armored vehicles. Even so, I have not found any evidence that the vehicles of the 4th AD carried these kits.

Given the total of 1179 authorized motor vehicle first aid kit 12-unit in the 4th Armored Division, I believe the division used only the 12-unit kits.

Given that the 24-unit just had two large wound dressings that the 12-unit did not have (and some of the other items were just more in quantity), using only the 12-unit kit made the supply system a bit easier and more efficient.

GAS CASUALTY FIRST-AID KIT:

This kit, supplied in the theater of operations based on one to every 25 individuals, and usually carried in vehicles, contains:

- Dichloramine-T in triacetin.

- Hydrogen peroxide solution (8%).

- Copper sulfate solution (10%).

- Eye and nose drops.

- Eye solution M-I.

- Cotton pads.

- Amyl nitrite.

- Pontocaine compound ointment.

- Protective ointment M-4.

The first thing to notice about these kits is that morphine syrettes were only added to these first aid kits when ordered by the commanding officer. They were not standard items in these kits. Individual soldiers were therefore not always able to administer morphine to casualties even when they had access to these motor vehicle kits. Giving morphine was a job intended for medical personnel.

The second thing to notice is the ever-present fear of chemical warfare in the European Theater of Operations as is shown by the preparations for it in first aid equipment.

We now know that chemical weapons were not used on the battlefields of Europe. In our minds, the use of chemical weapons is typical for WW1. In this mindset, we may fail to realize just how real this fear was for the men fighting in WW2.

In the documents I have read in the course of this research, I have found multiple references to the fear of a German attack with chemical weapons. They are mostly found at times when the German Army was threatened with a major setback.

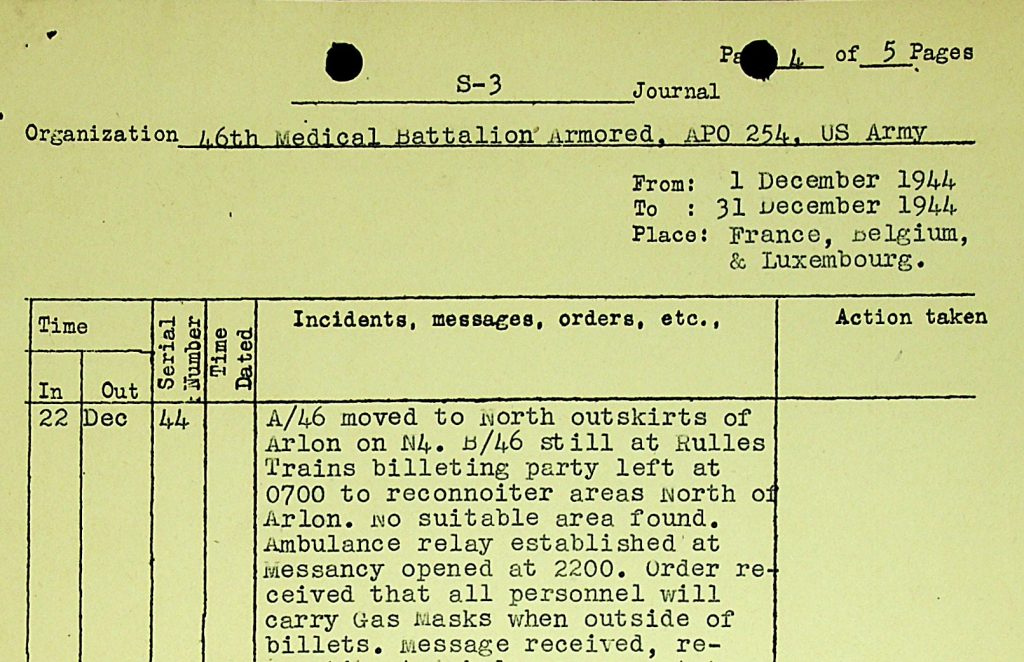

For example, we can see that orders were given within the 4th AD to carry gas masks outside at all times on 22 December 1944, so right at the start of the Third Army’s counterattack into the Bulge.

Another example is the Chief Surgeon ETO Circular Letter No. 25 March 45.

This letter was written when the Allied armies were about to cross the Rhine River, breaching Germany’s last natural barrier. In it, the need to stay alert for, and the need to maintain knowledge of, chemical warfare was emphasized.

With the final phase of the war in Europe starting, the Army wanted to be prepared for a desperate, last-resort use of chemical weapons by the Germans in an attempt to prevent their imminent defeat.

Conclusion

With a minimum of training and equipment, the men of the US Army had to start, often lifesaving, first aid treatment of their casualties.

As we shall see in part 2 of this series, the next step after first aid was the medical care provided by the, sometimes only slightly better trained and equipped, company aid men of the medical detachments.

Pingback: Medical Evacuation and Treatment Series. Part 3: First echelon evacuation. - Patton's Best Medics

Hey just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The words

in your post seem to be running off the screen in Safari.

I’m not sure if this is a formatting issue or something to do with internet browser compatibility but

I thought I’d post to let you know. The design look great though!

Hope you get the problem solved soon. Thanks check credit score for free

Thank you for your comment. I will look into this problem asap. And thank you for your compliment! Reinier

Pingback: Homepage