Shock is a life-threatening condition caused by failure of blood circulation, causing inadequate oxygen delivery to the tissues and cells of the body. The effects of shock are initially reversible, but can rapidly become irreversible, resulting in multiorgan failure and death. There are several possible causes and we now recognize different types of shock: septic shock, hemorrhagic shock, etc.

The experiences gained during the War in treating severely wounded soldiers led to a better understanding of shock, and a marked advance in the treatment of shock. This unquestionably saved a great number of lives and is one of the major medical breakthroughs of WW2.

In this two-part series, I will take a look at the developments during WW2 in medical knowledge about shock and at the developments in the treatment of shock in the US Army. This first part will look at the initial understanding of shock at the beginning of the War and the development of the blood plasma program. Part two will look at the developments in the understanding of shock and whole blood transfusions in the US Army during WW2 as a consequence of experiences in the field. If you are interested in a more extensive description of the entire blood program during WW2, I recommend reading Blood Program in World War II.

Initial ideas on shock

At the start of WW2 shock was not fully understood. Part of this problem was reflected in the unclear definition of the term shock. Before the War, different definitions were proposed. In 1941, the definition was split into two: primary and secondary shock.

In 1942, the War Department’s TM 8-210 Guides to Therapy for Medical Officers (March 20, 1942) Page 53-61, still used these two terms. It started its description of “Secondary or wound shock” by first describing primary shock: “Primary shock refers to a condition of collapse that may follow quickly after the receipt of an injury; It is usually to be explained on a neurogenic (reflex or psychic) basis”.

We now call this vasovagal collapse or syncope. It is the reaction of fainting when confronted with an unpleasant stimulus such as the seeing of blood or experiencing pain.

The manual continues to describe that this type of shock is usually of short duration, “although it may progress into the secondary type”.

“Secondary or wound shock” was the term used for what this article is about. For clarity in reading, I will simply use the term shock for this in the rest of this article.

Concept of shock at the start of WW2

During WW1, much experience was gained in the treatment of casualties. Significant progress was made in the treatment of severely wounded men. One of the major steps taken during the war was the use of blood transfusions. Most were done directly from donor to patient, but the use of the preservative sodium citrate made the storage of blood possible for a short time.

In 1920 Major W. Richard Ohler, MC expressed the firm opinion, based on his experiences during WW1, that the most important single factor in shock was hemorrhage and that the degree of shock depended upon the amount of blood loss. The therapy for shock, therefore, was the transfusion of blood to compensate for this loss of blood.

Probably due to laboratory tests conducted on animals, during the interwar years, the lessons of WW1 were forgotten and the focus shifted. It is a clear example of how the progress in medical knowledge is not a straight line. Sometimes medical science takes a step back, forgets lessons learned, to then find a way to the progress of our knowledge.

At the start of WW2 the concepts of shock and shock therapy that were generally accepted were:

The single most important factor in shock is the reduction in blood volume present in the peripheral circulation. It results from the loss of plasma into the extravascular (outside the blood vessels) tissue spaces. Most therapeutic efforts must be directed towards overcoming this loss in volume.

One of the most used arguments for this concept was that in shock, hemoconcentration (blood becomes more “concentrated”) was usually present in blood tests. This was thought to reflect the loss of plasma. Plasma is the liquid part of blood that remains after the blood cells are removed.

The idea that loss of plasma was the single most important factor in shock was further strengthened by laboratory tests. In these tests, animals were bled and then reinfused with their plasma, which revived them, even after 75-80% of their blood was first removed. Medical Department US Army, Blood Program in World War II.Page 30-31 ; The Army Medical Bulletin No.58 (Oct 41)Page 38-60.

Concepts in treatment

Understandably, these concepts of shock led to the belief that the transfusion of plasma was the correct treatment to compensate for the loss in blood volume, even when tests performed on lab animals and effects encountered on battlefields could hardly be expected to be equal. Lab animals in their cages did not have to survive the subsequent transportation in ambulances and surgical treatment that wounded soldiers had to endure.

The use of plasma also had some significant practical and logistical advantages over the use of whole blood. Transfusion op plasma does not require blood typing first since the factors that determine blood types are part of the blood cell. Furthermore, by this time the technical possibilities for the processing and storage of plasma increased dramatically with the development of freeze-drying. This made the transportation, storage, distribution, and use of plasma far more practical than whole blood. Plasma could be used even in the most forward areas of the front. It is clear that not everybody was convinced that plasma alone could compensate blood loss in shock, but many of the medical doctors who believed that only whole blood could be effective in treating shock did not believe that whole blood transfusion would ever be a practical option in forward areas during the War. So no significant opposition was voiced against the development of the blood plasma program as the main treatment of shock in the Armed Forces.

The blood plasma program

In 1940, the British appealed to the Americans to help supply them with urgently needed supplies for their war efforts. Part of this was for supplies needed to treat shock. This appeal resulted in the “Blood for Britain” program. Mostly based in New York, this program combined many of the most recent developments in the subject of treating shock.

One of the leading organizers was Dr. Charles Drew, an African-American Surgeon whose dissertation “Banked Blood, a study in blood preservation”(June 1940), reported many progressions in the storage of whole blood and made many recommendations for the establishment of local blood banks.

Dr. Charles Drew

His recommendations for blood banks created the foundation for the “Blood for Britain” program. It established the best method for collecting, transportation, testing, and storing the donated blood. The donated blood used in the “Blood for Britain” program was processed into liquid plasma. This means that the plasma was transported and stored in its liquid form. The experiences of this program showed that a system of collecting and processing donated blood into plasma was practicable, but that processing plasma into its freeze-dried form would be preferable for transportation and storage.

All these lessons were immediately incorporated into the blood plasma program for the US Armed Forces.

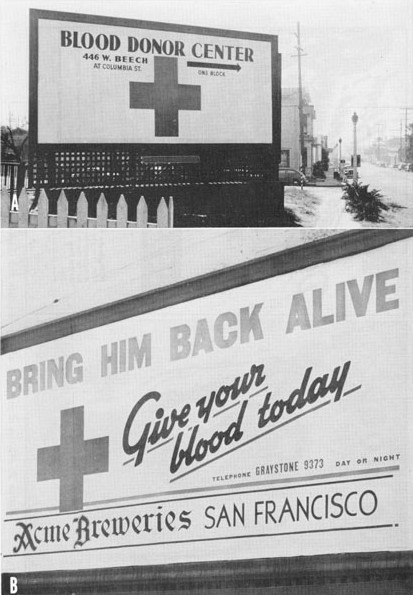

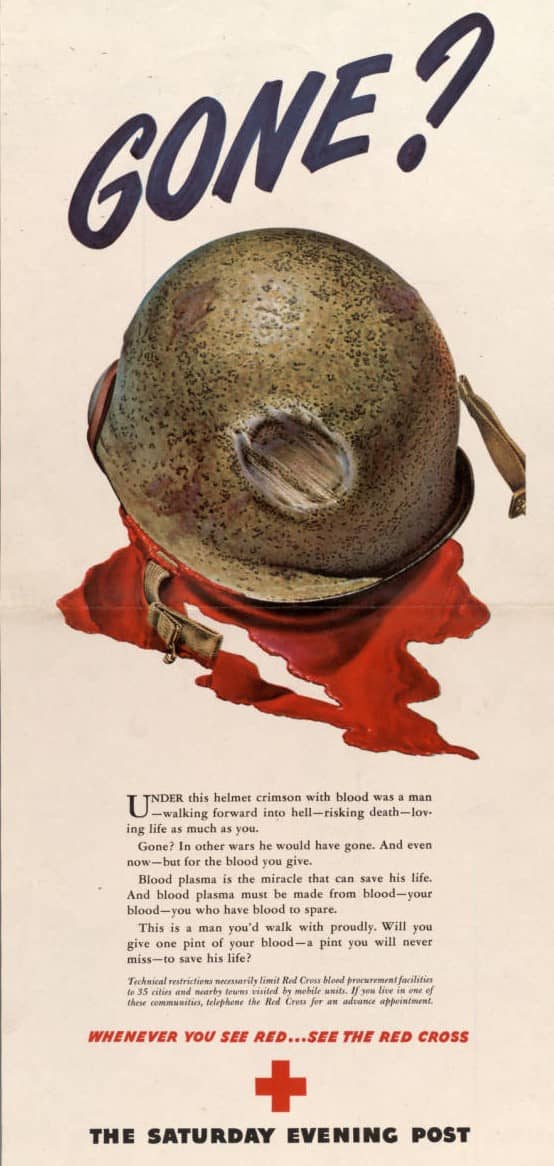

The organization for donating blood became the responsibility of the American Red Cross. The first Red Cross donor center was opened in New York on February 4th, 1941. The last center to open was the 35th Red Cross donor center, located in Fort Worth, which opened in January 1944.

The Red Cross assumed that no more than three donations from any donor would be needed. So every donor received a bronze emblem for the first donation and a silver emblem for the third donation. When more and more donations were needed so-called Gallon Clubs were formed in several cities, where donors received red, white, and blue ribbons for their silver emblem signaling 1, 2, or 3 gallons of blood donated.

Blood donor pin

To further encourage donor participation in the program, it became possible from December 1944 onwards for donors to inscribe their name onto the Red Cross label attached to the blood plasma package send to the front. This was rather symbolic as the processed blood plasma was not identifiable to one particular donor. Still, about a third of the donors did inscribe their names on the label after it became an option.

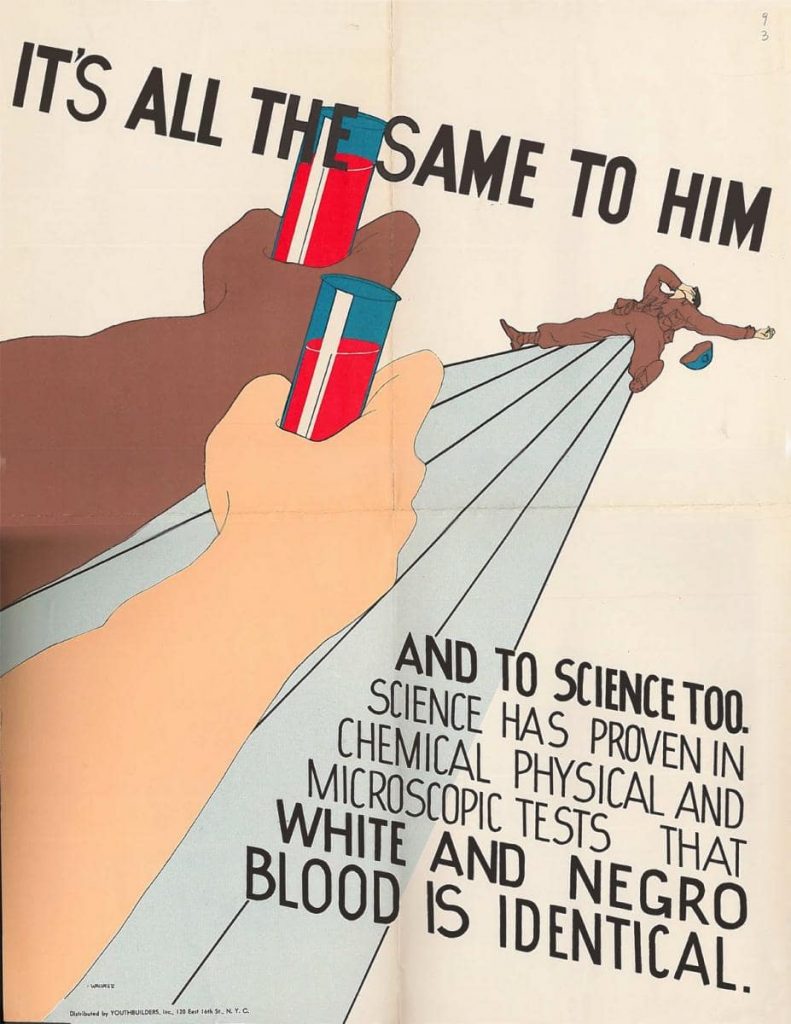

At first, the Red Cross refused African-American donors, making it even impossible for one of the leading figures in its establishment, Dr. Drew, to donate. After protests from Dr. Drew and other African-American leaders, the Red Cross changed its policy. It started to accept African-American donors but would keep their blood and the plasma processed from it strictly segregated. This was, unfortunately in line with the segregation of the Armed Forces still enforced during the entire War.

Poster protesting segregation of blood.

By the end of the War, the Red Cross had collected more than 13 million pints of blood. Of these 10,299,470 pints had been processed into dried plasma.

Red Cross Donor Posters.

Processing the blood

During the War, eight commercial firms processed the donated blood into dried plasma packages for the Armed Forces. This process meant testing the donated blood (for diseases such as syphilis), centrifuging it to extract the blood cells, drying it, and finally packaging it. The first contract was made with Sharp and Dohme for 15,000 packages. This contract was relatively small because the production capacity had not yet been expanded enough and it was seen by the supervising committee as a trial contract.

All through the War, the full utilization of the processing capacities of the eight companies depended on a well-coordinated “production” of the Red Cross donation centers. Too few pints of blood collected meant that the companies could not produce dried plasma in their maximum capacity. Too many pints donated meant unnecessary wastage of collected blood.

The Armed Forced requirements for the fiscal year 1941-1942 were first set at 100,000 units but were soon raised to 200,000 units in July. After Pearl Harbor brought the US into the War, the requirements for the fiscal year 1942-1943 were set at 1,640,000 units. Contracts with the eight companies soon were made for 350,000 units per contract.

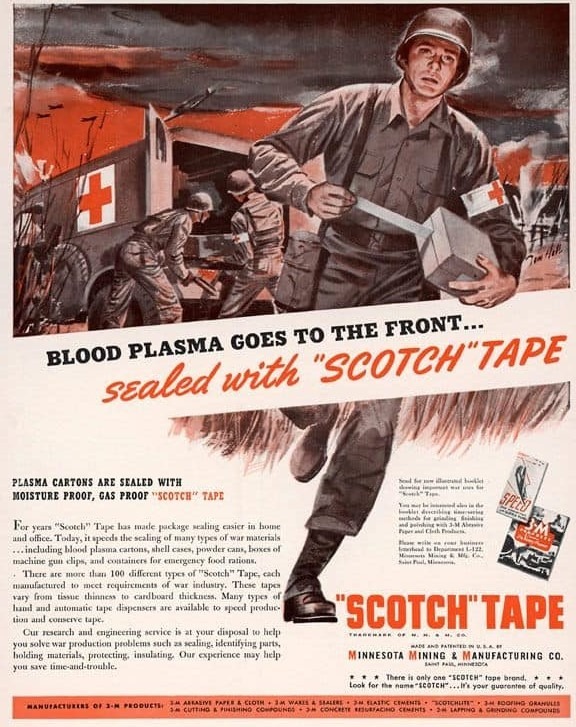

Plasma packages

Right at the start of the blood plasma program the need for practical packaging was recognized. It had to include all the necessary materials for a transfusion. The package had to be strong enough to be transported and used under combat conditions.

At a meeting of the Subcommittee on Blood Substitutes in April 1941, a package was proposed that was accepted in July 1941. This became the standard package for blood plasma during WW2.

It consisted of:

- A 400cc. bottle containing dried plasma obtained from 300cc of plasma. This bottle had cloth tape around the bottom for suspending the bottle during the transfusion.

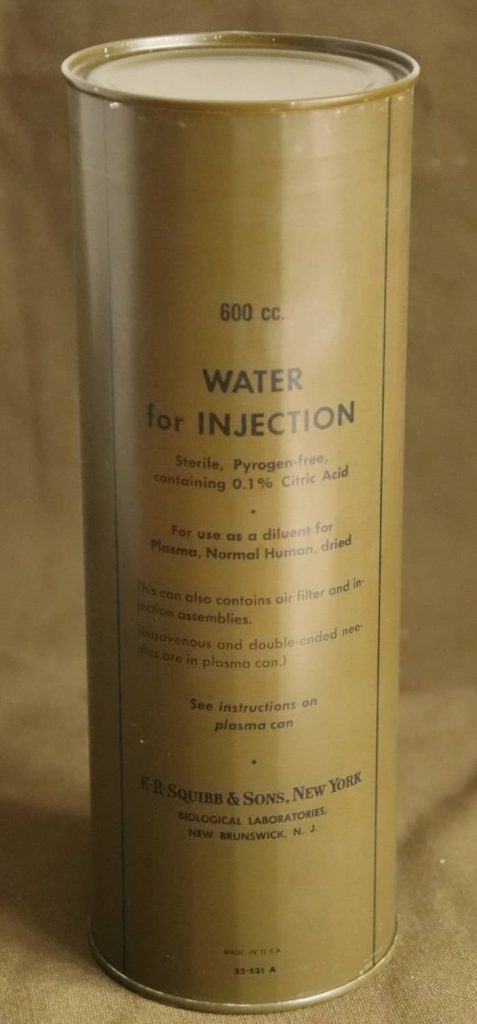

- A 400cc. bottle containing 300cc. distilled water.

- Equipment for adding the distilled water to the dried plasma: a double-ended needle and an airway tube (with a needle and a filter).

- Injection equipment: a rubber tube with a glass cloth filter with a needle on both ends.

The bottle containing the dried plasma, the double-ended needle, and a clamp were placed in a tin can that was sealed in a vacuum. The bottle containing the distilled water and the intravenous injection set and the airway tube were placed in a similar sealed tin can. These tin cans were an existing standard item in the Navy, used for the priming charge of explosives. This helped to speed up the production. Both cans were then placed in a tape-sealed fiberboard box.

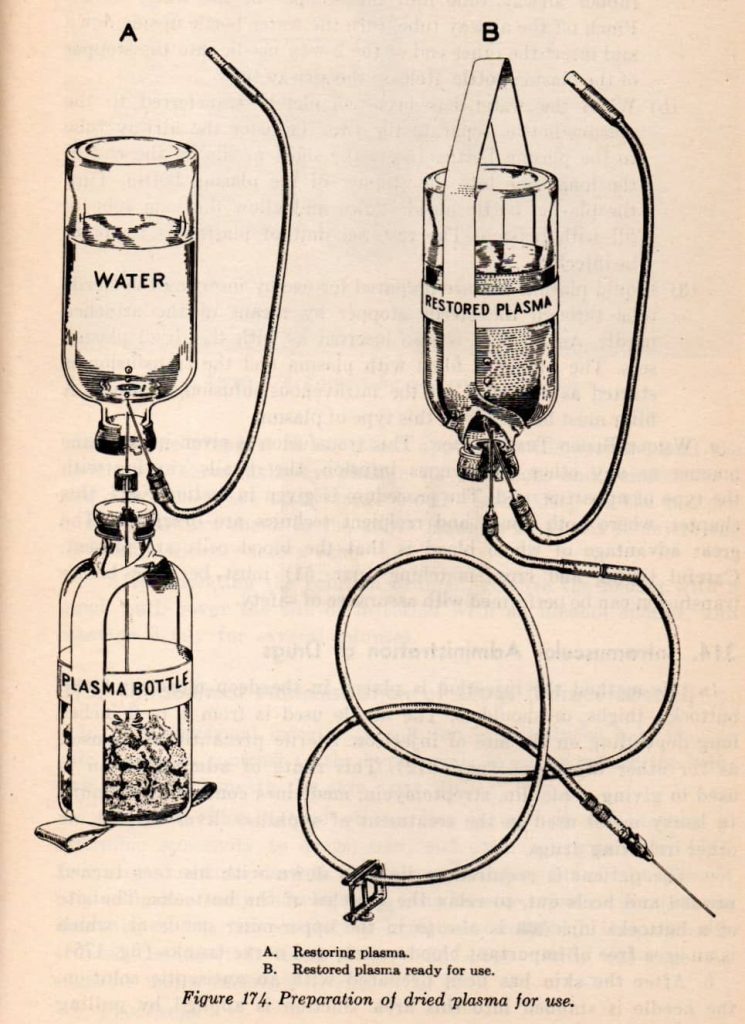

Instructions for plasma transfusion.

Advertisement for Scotch Tape.

Standard Army and Navy Packages Plasma. (collection of Ben Major)

Contents of the can containing the distilled water bottle.

These packages produced around 250cc. of reconstituted blood plasma each.

As early as May 1941, there were concerns that 250cc. of plasma was not enough plasma to resuscitate a wounded soldier. At this time it was still thought that larger cans would be difficult to transport and use in the forward areas of combat. It was believed that a smaller amount given at the front was more beneficiary than a larger amount administered further back. Also to avoid production delays it was decided to proceed with the production of the 250cc. packages. At the same time, it was decided to start the development of a larger package that production could switch to at a later date.

By November 1942 a new package, using larger bottles packed in larger tin cans could bring the administered quantity of plasma per package to 500cc. These packages were only 2 inches longer than the 250cc. packages so 18 larger packages used the same space as 24 smaller packages, but they carried the same amount of plasma as 36 smaller packages. The switch to these larger packages was not only medically beneficial to the wounded soldiers, but it also reduced the amount of shipping space needed. This was an ever-present concern during the War since everything produced in the USA had to be shipping overseas to be used in the fighting.

These larger packages also reduced the amount of (critical) material used. For example, the reduction in rubber tubing used by switching to the larger package amounted to many hundreds of thousands of feet. Also, the amount of stainless steel used on the needles would be reduced by half.

Production of the larger packages did not begin until July 1943 due to different problems in switching the production of plasma to the new size. Two companies, Ben Venue Laboratories and Park, Davies, and Co. continued producing the smaller, 250cc. packages until the end of the War.

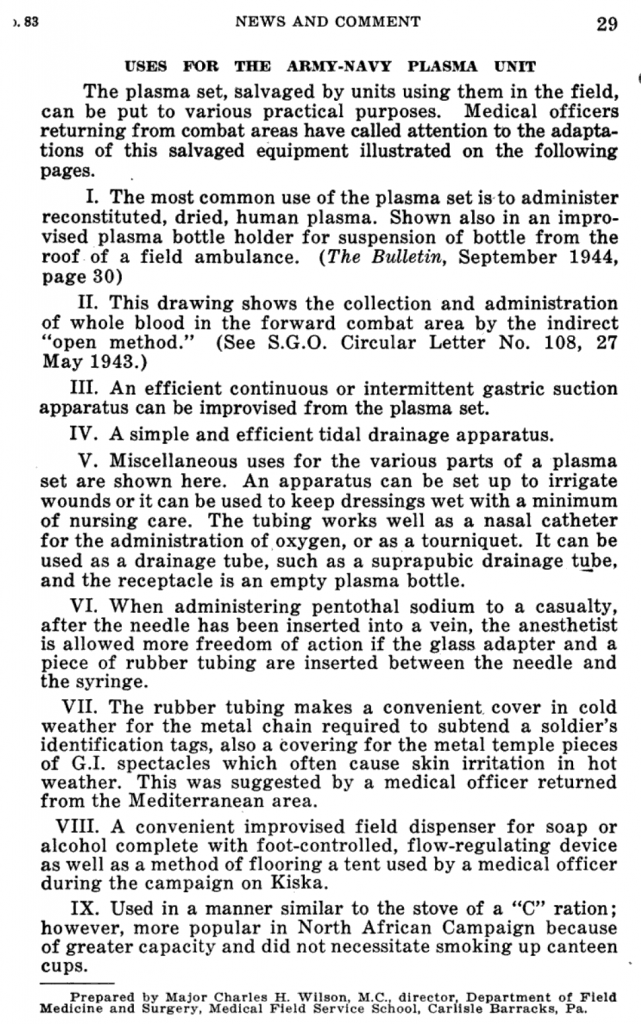

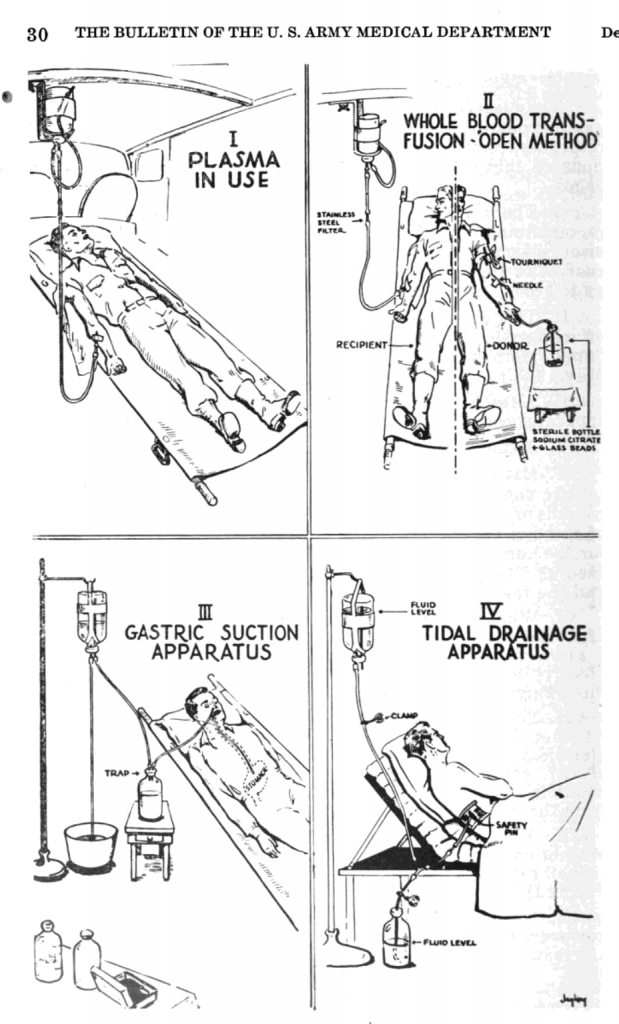

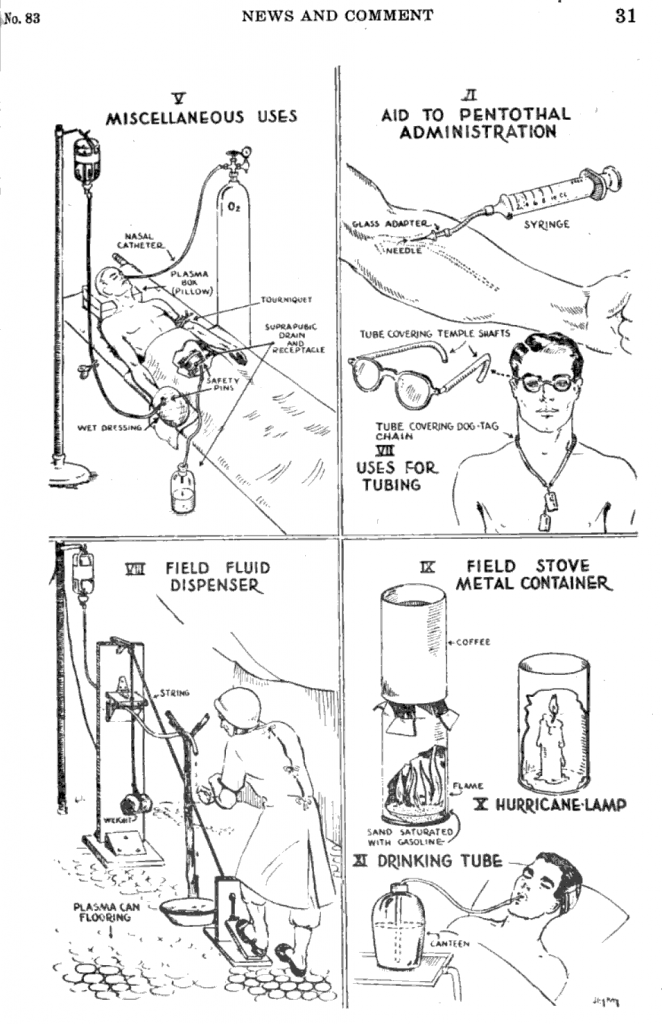

The critical materials used in the plasma packages did not go to waste at the front. Some very inventive recycling was reported in the Bulletin of the US Army Medical Department no 83 (December 1944) Page 29-31:

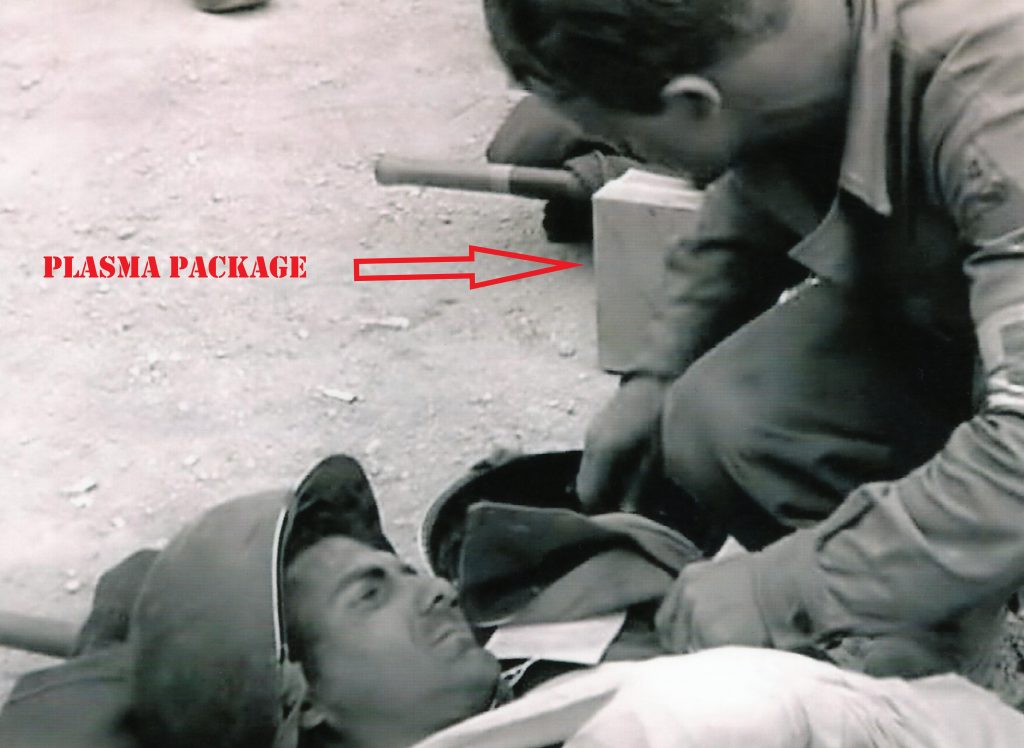

The bottle containing the plasma came standard with a cloth tape to suspend it during transfusion, but no standard hooks or stands were produced to hang the bottle on. This is why we can often see medics in photos holding the bottles up during transfusion, or we can see some improvised stands.

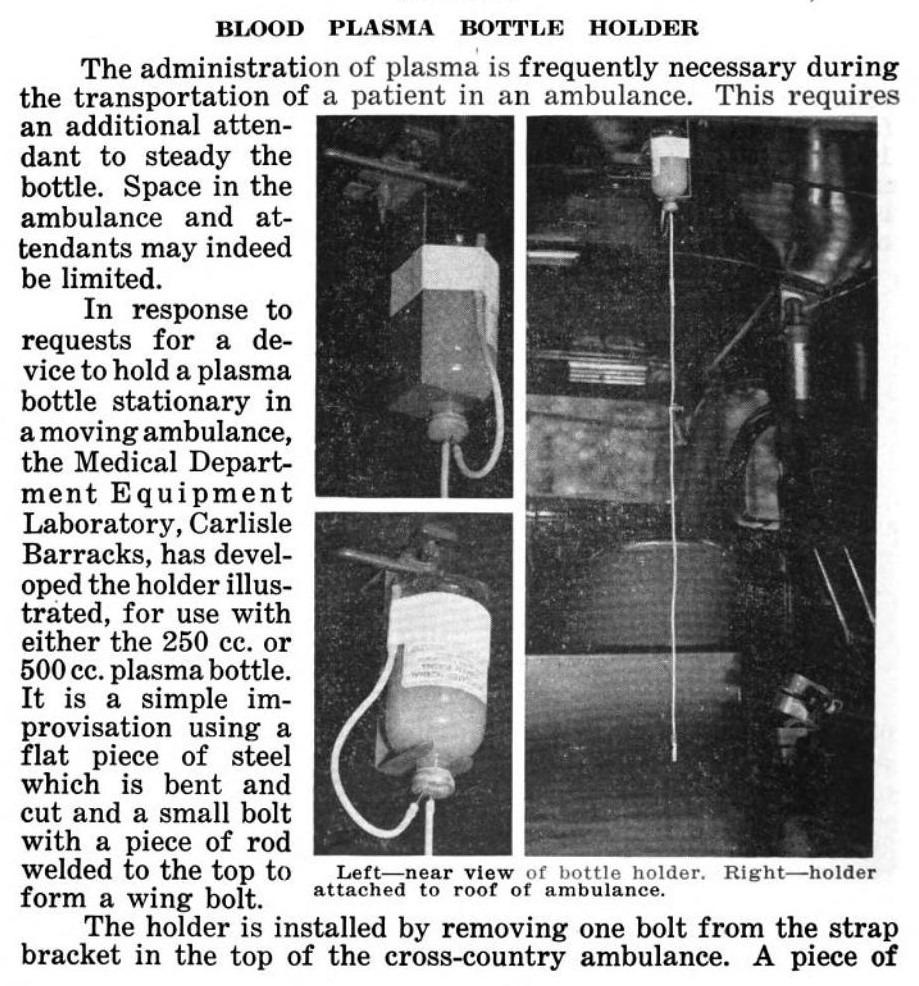

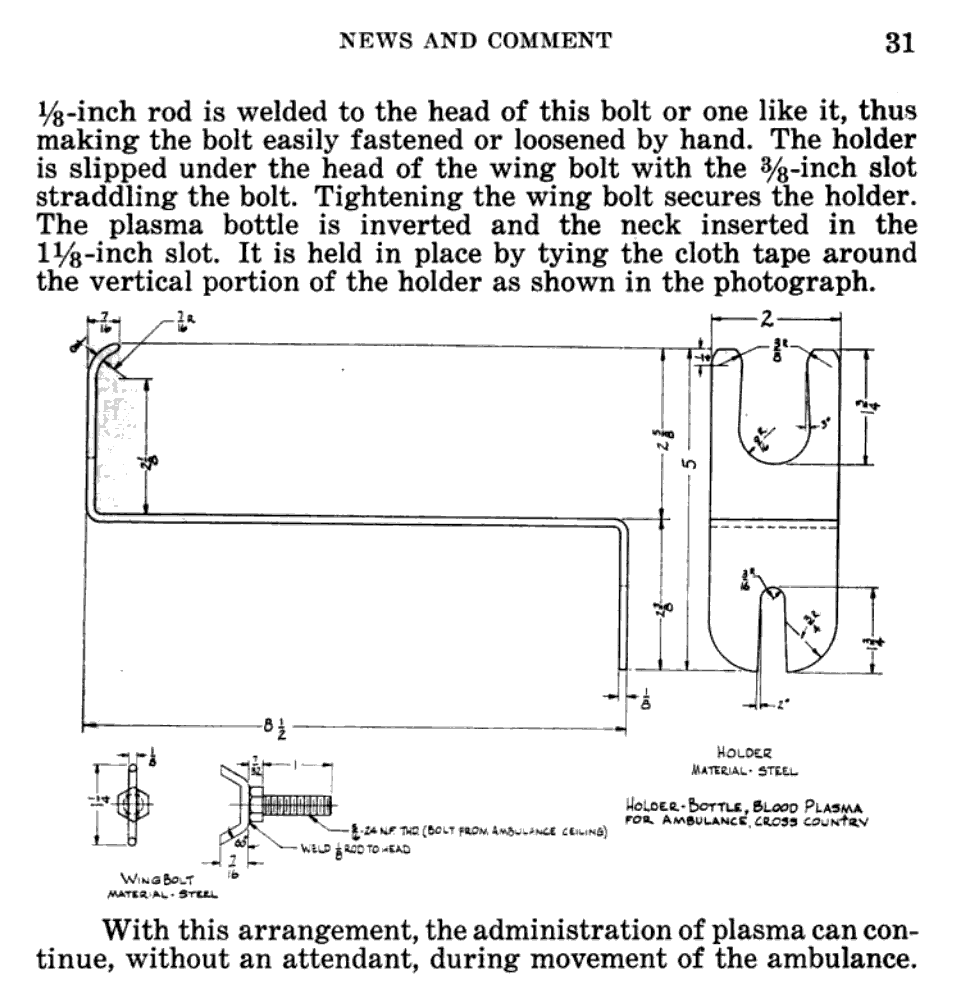

Ambulance suspension bracket as proposed in the Bulletin of the US Army Medical Department no 80 (September 1944) Page 30-31.

Plasma bottle being held for transfusion.

Improvised plasma stand using a shovel an a tent pole.

Blood plasma use in the 4th Armored Division

For my research into the medical service within the 4th Armored Division, I wanted to find out where exactly in the evacuation chain blood plasma was used within the division.

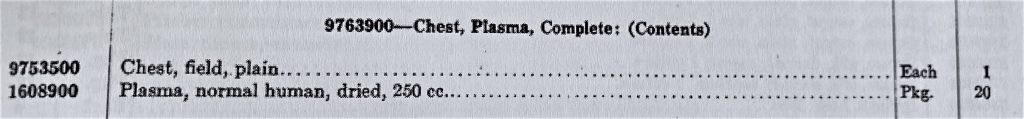

The TO&E for an armored medical battalion shows that the battalion headquarters supply section had 2 Chests, Plasma, Complete (9763900). Each of these chests contained 20 packages of 250cc. blood plasma.

Medical Supply catalog

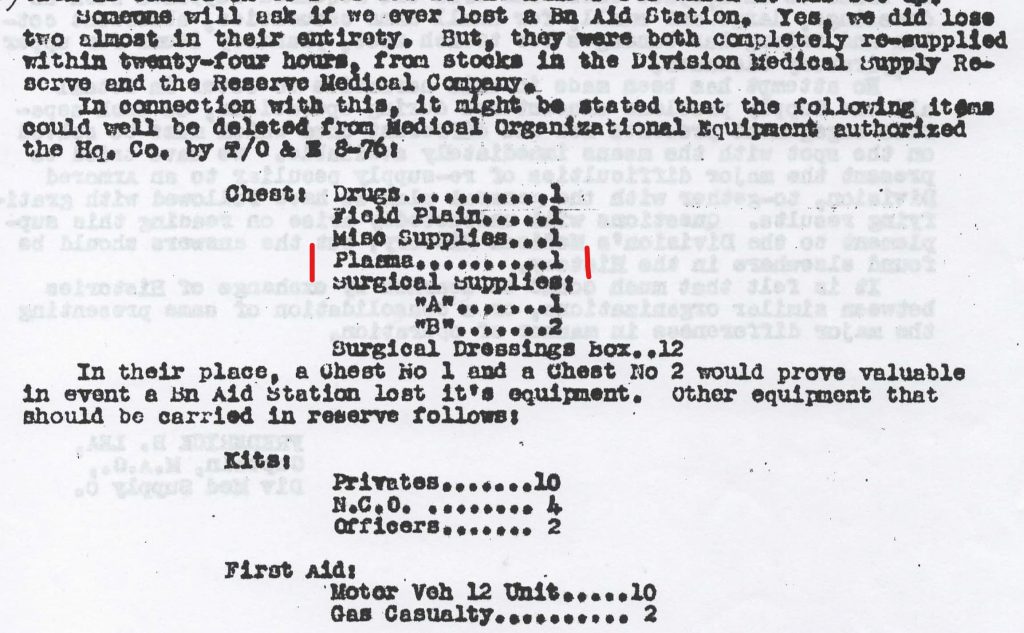

It is interesting to note that the battalion S-4, Capt. Frederick Lea, recommended deleting one of the plasma chests stored within the battalion supply section. Experience had shown that this second chest was not often needed and that the storage space could be better used for other supplies.

46thAMB supply report 1944.

The TO&E also shows that each of the three medical companies’ clearing platoons had 2 of these chests.

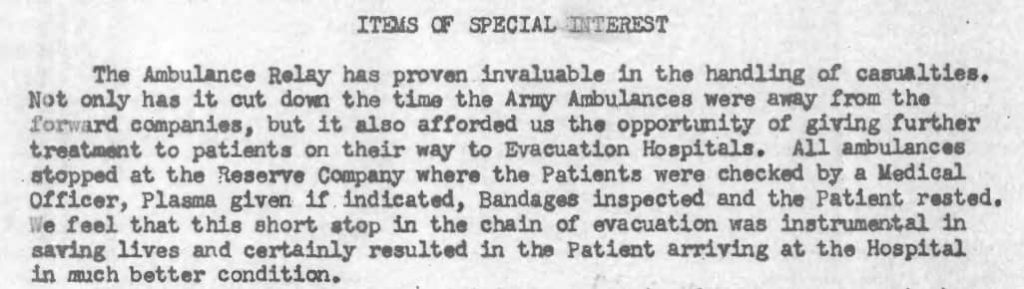

46thAMB Reserve medical company Relay Station.

This report is one example showing the use of plasma at the clearing stations of the 4th Armored Division.

None of the medical detachments within the division had plasma chests or plasma packages in their TO&E.

This does not mean that plasma was not used within the medical detachments although one might think that. The TO&Es show us where the plasma was stored within the supply chain.

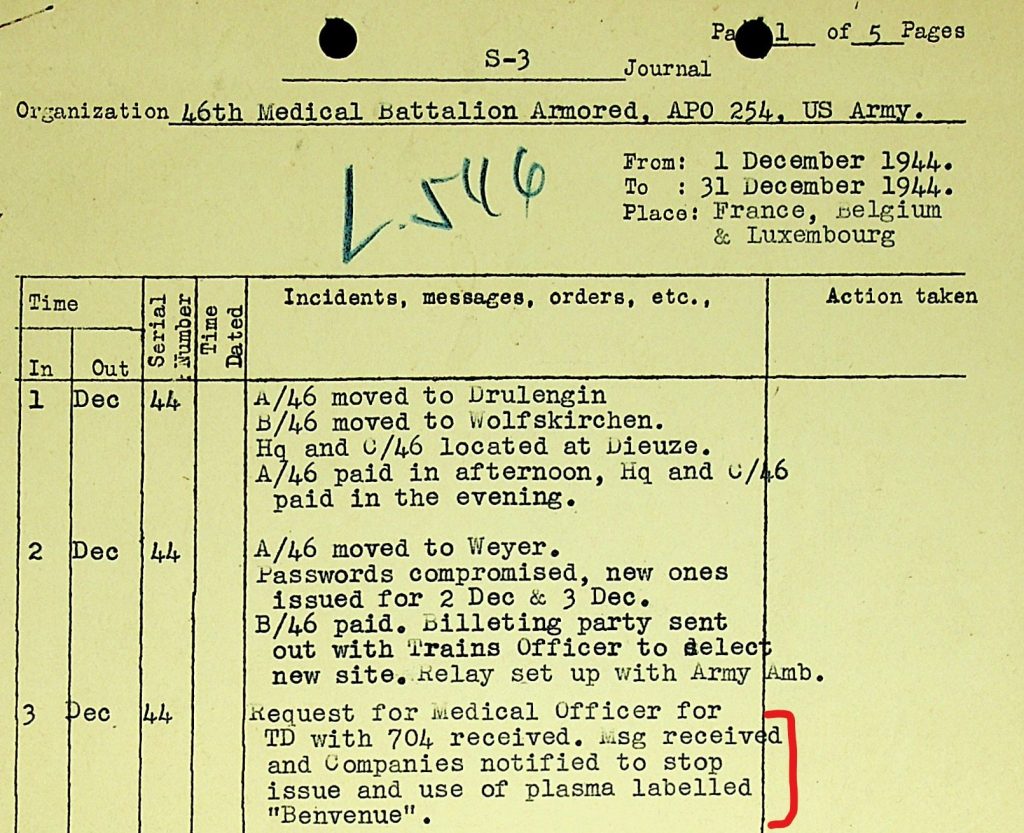

This message was documented in the S-3 Journal of the 46th AMB.

This shows that the medical companies not only used but also issued plasma (to the medical detachments). In my article on the medical supply chain I have explained that many of the medical supplies for the medical detachments came from the medical companies.

The reason why the units were instructed to stop using the plasma produced by Ben Venue Laboratories is unclear. Perhaps it had to do with the fact that Ben Venue continued to produce 250cc. packages of plasma when experience had shown this volume to be inadequate. Perhaps a batch of Ben Venue plasma failed to pass quality control.

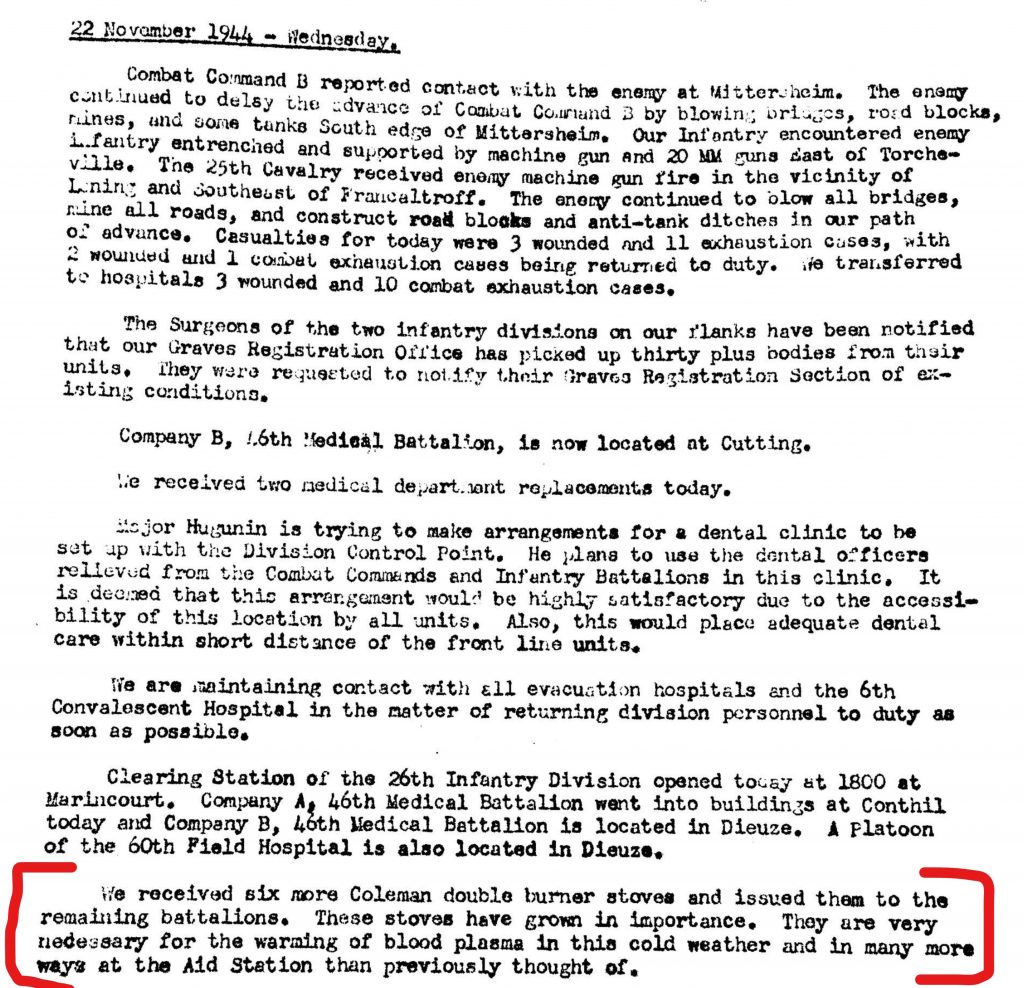

Further documentary evidence for the use of plasma at the battalion aid stations is found in the Division Surgeon’s Journal.

The extra Coleman burners Model 523, normally used to sterilize medical instruments, were sent to the (medical detachments of the) battalions. The need for the personnel of the medical detachments to warm the plasma gives sobering evidence under what terrible weather conditions the men had to fight during the fall and winter of 1944/1945.

Besides these documents, I have found photographic evidence that plasma was used at battalion aid stations. These photos, taken in front of the Champagne Theater (on the Boulevard Gambetta) in Troyes, France show the medical personnel of one of the attacking battalions transfusing casualties with blood plasma.

4th Armored Division in Troyes, France (26th August 1944).

As a side note: the name Philips on the driver’s side of the ambulance in the photos probably makes this the ambulance driven by Robert M. Philips, 35290180, Co A, 46th Armored Medical Battalion.

So the documentary and photographic evidence clearly show that plasma was used at the battalion aid stations. However, I have found no evidence (yet) that plasma was used forward of the battalion aid stations. It is possible though, that the company aid men did carry and use plasma. Especially the company aid men in an armored division, traveling in their jeeps, had enough space to carry plasma packages. From a medical point of view, starting transfusion as soon as possible by issuing plasma to the company aid men makes sense.

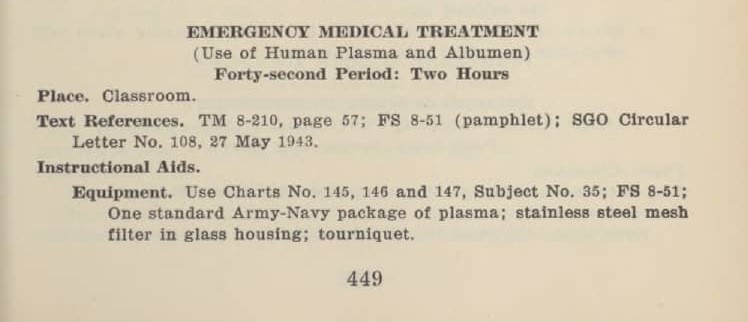

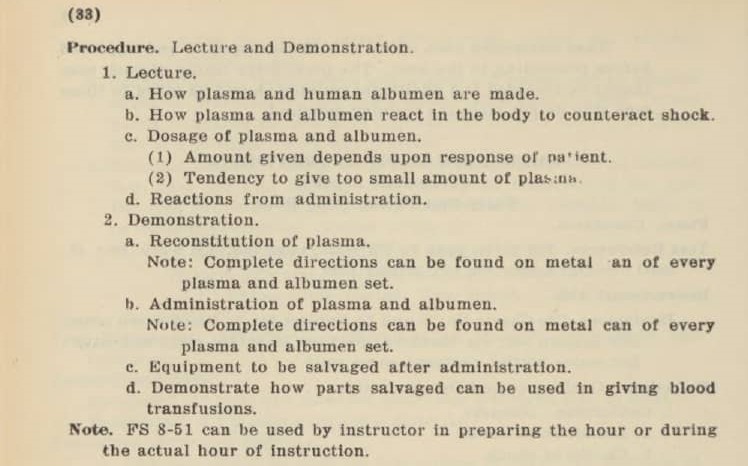

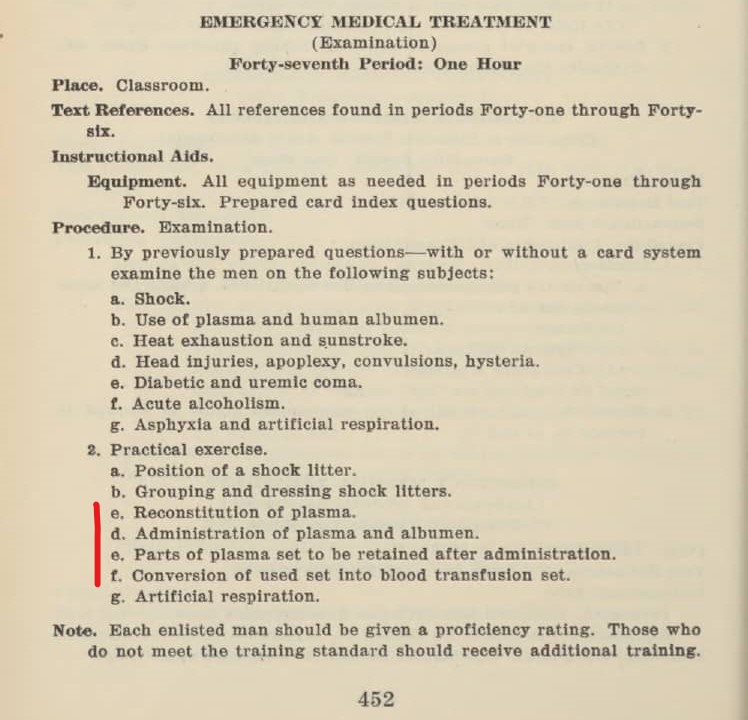

According to the MTP 8-101 (June 1944), Mobilization Training Program for medical personnel, the men were trained in the use and administration of plasma. They also had to pass a test on this subject.

So, it is clear that the medics were trained to administer plasma and it is therefore entirely possible that the company aid men did bring it in their Jeeps to start this treatment as far forward as possible. Although it still does not prove it.

It is interesting to note that part of the examination was on the conversion of the used plasma sets into blood transfusion sets. I will explain more about this is part two of this series.

Pingback: SHOCK TREATMENT IN THE US ARMY DURING WW2. PART 2: WHOLE BLOOD. - Patton's Best Medics