The medical concepts of shock and its main cause at the beginning of WW2 led the US Armed Forces to rely on the transfusion of blood plasma as the main therapy. For more information on this and the successful blood plasma program during the War, I invite you to read part 1 of this series.

Wartime experience

The US Army Medical Department was convinced that the dried plasma available at the front was very effective in combatting shock. Experiences in North Africa (1942-1943), and later in Sicily and Italy (1943-1944) soon forced the doctors at the front to reevaluate the prevalent concepts of shock and the effectiveness of the plasma therapy. It was often found that casualties who had been resuscitated by plasma transfusion appeared to be stabilized when measuring their blood pressure. However, their condition soon deteriorated, especially when they had to undergo major surgery after their “stabilization”.

Plasma simply proved incapable of full resuscitation. More and more evidence was found that casualties not only needed the transfusion of plasma, but they needed the transfusion of blood cells to restore their capacity to transport oxygen to their tissues and cells. This could only be accomplished by whole blood transfusion.

The British Army by contrast had already set up a whole blood transfusion system during 1939 when it became involved in the War. Its results in resuscitating shock patients proved far superior to the US Army’s results in its early campaigns.

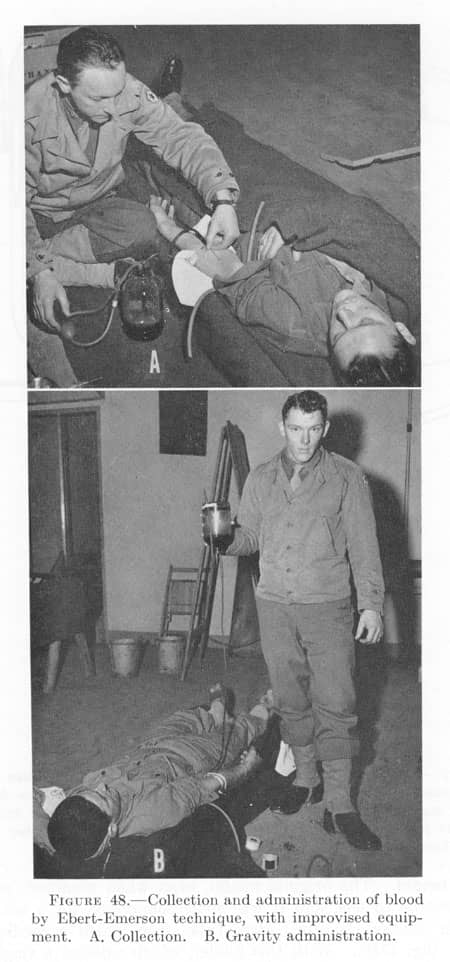

By December 1942 the first reports from the field were sent up the chain of command declaring the need to provide hospitals with materials for whole blood transfusions. As no materials were available to the US Army doctors in the North-Africa Theater of Operations, the medical personnel started to improvise their own transfusion sets with materials borrowed from the British and the French.

Slow response from the Surgeon General

Despite the mounting evidence that whole blood transfusions were vital in combatting shock, and a British system ready to be copied, there remained a strong reluctance in the Office of the Surgeon General to get a whole blood transfusion program activated for a long time. It seems that there were two main reasons for this:

1)The Surgeon General remained convinced that plasma alone was enough to resuscitate shock patients as was still the consensus among physicians in the USA.

2)Sending materials for whole blood transfusion meant the need for additional shipping space for medical supplies. Shipping space remained a scarce commodity during the War.

At first, the Surgeon General did not respond to the signals from the field. It was this failure to address the problems experienced in the field that led to several independent initiatives to solve the problem. The Division of Surgical Physiology of the Army Medical School started the development of a suitable transfusion set in the USA.

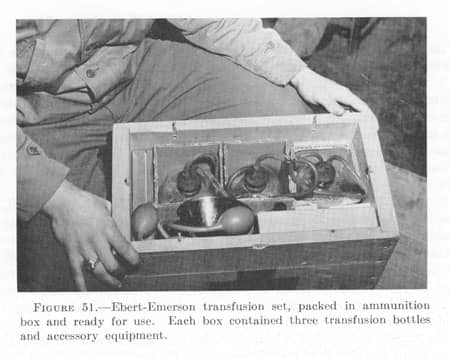

In the ETO, Majors Emerson and Ebert started their own development of a transfusion set, early 1943. For the preservation of the collected blood, they collected blood in reconstituted dried plasma as this contained enough preservative to keep the collected blood usable for some days.

In the Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTOUSA), the Chief Surgeon developed a blood transfusion system, using hospital personnel as donors and British material.

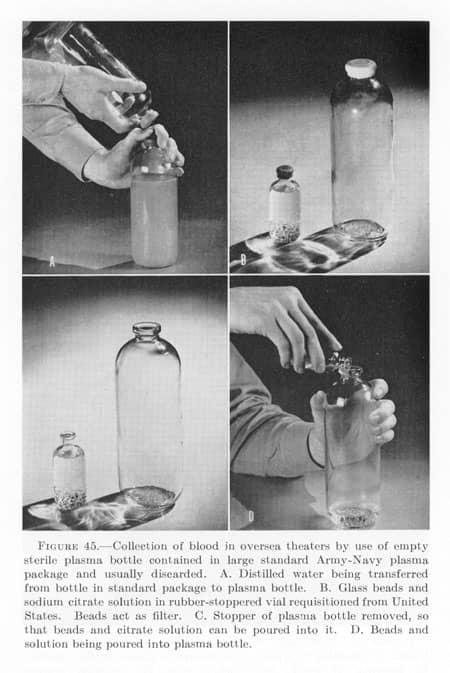

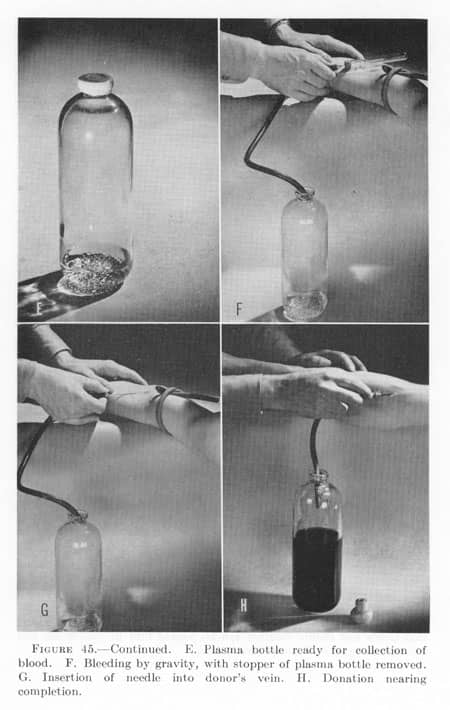

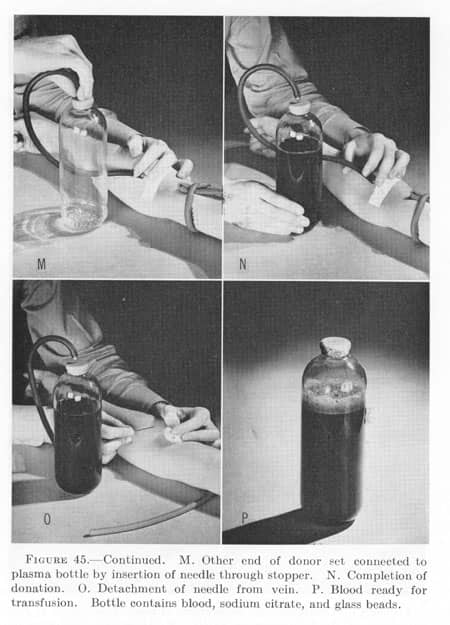

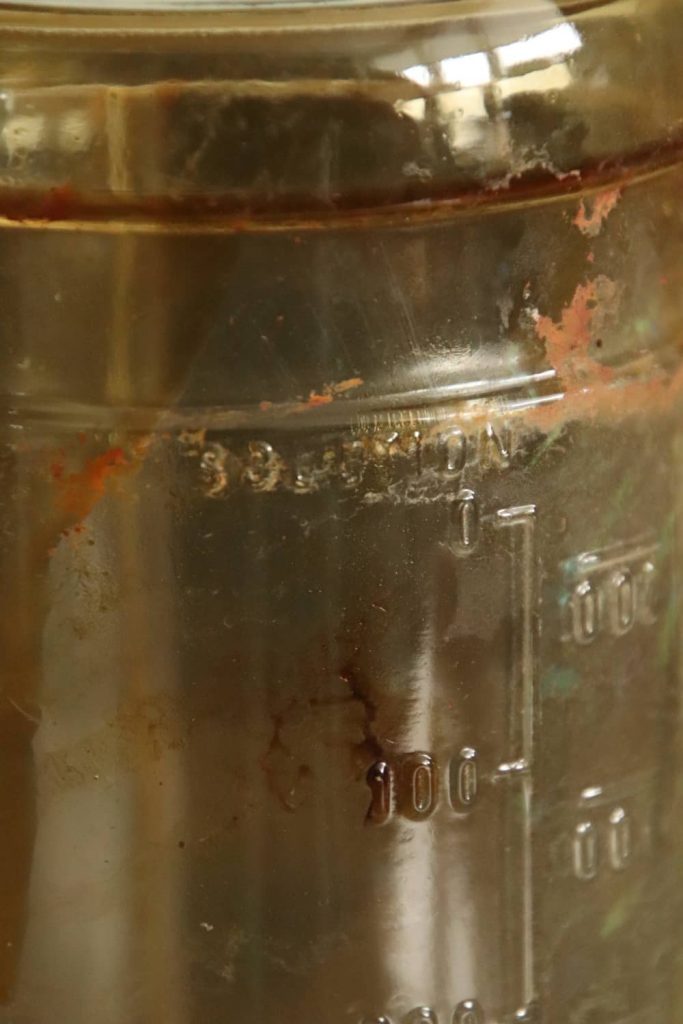

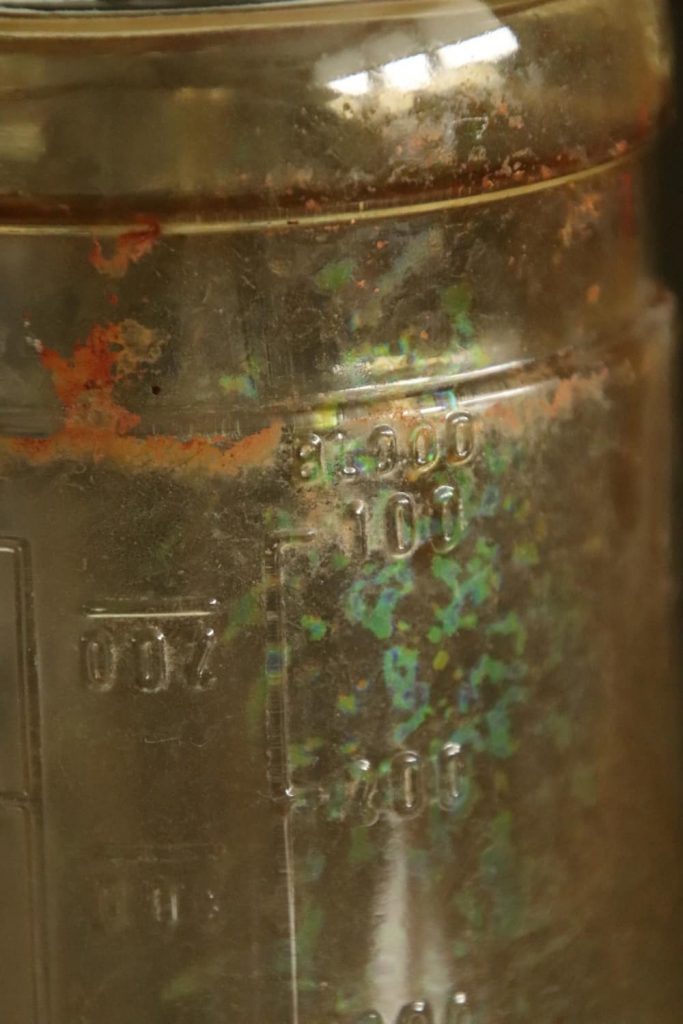

In answer to the requests from the medics in the field, the Surgeon General sent an instruction, no sooner than May 1943, that allowed the use of whole blood transfusion in General Hospitals (only ed.), using donors from within these units and improvised transfusion sets improvised with used plasma bottles. As no adequate preservative was available to keep the blood thus collected (in open bottles) for any significant amount of time, the instructions ordered the donated blood to be used within a few hours. This severely limited the usefulness of blood transfusions as they could not be collected and stored in adequate amounts prior to any major military action. Blood transfusions needed to be more or less ad-hoc. Using “old” plasma bottles prevented the need for additional materials to be shipped, solving one of the Surgeon General’s main concerns.

“Plasma bottle” transfusion set:

Clearly, this instruction was a compromise and it did not solve any of the problems faced by the doctors in the field It therefore only kept the need for local improvisation active. When the Ebert/Emerson set was sent to the Surgeon General for approval, he rejected its production and use, as it did not comply with his May 1943 instructions.

In September 1943, General Hawley, the Chief Surgeon of the European Theater of Operations (ETOUSA), send the Surgeon General a message explaining that the Ebert/Emerson set was developed for use in forward medical installations, where transfusions of whole blood were urgently needed, not just in General Hospitals as the May 1943 instruction ordered. Also, it was impossible to implement the May 1943 instructions in the ETO as there were no large plasma sets (500cc.) in the UK at the time. The May 1943 instructions required these large plasma bottles to be implemented. It was this last argument that led to the reluctant acceptance by the Surgeon General to ship limited numbers of the newly developed transfusion sets developed by the Army Medical School. Incidentally, this was the first time the physicians in the ETO heard of the existence of this type of transfusion sets.

At the same time, the landings at Salerno, Italy proved that the blood bank system in the hospitals developed in the MTOUSA was inadequate. The personnel of the hospitals alone could not provide enough donated blood. A more centrally organized system, using rear echelon personnel as donors was needed to provide the hospitals with enough blood to treat the many shock patients evacuated from the battlefield. This new system, organized by the Fifth Army in Italy started to provide blood, collected and processed by its own transfusion unit, to its hospitals in February 1944. This system proved well suited for the Fifth Army. This experience was shared with the planners in the ETO.

So, by improvising the US Army medics in the theaters started making the necessary steps towards a working system of whole blood transfusion available at the forward medical installations.

Memo to the Surgeon General

In October 1943, Lt.Col. Kendrick, MC, special representative on blood and plasma for the Office of the Surgeon General, wrote a memo including all his conclusions based on his visits to the theaters in Europe. In his memo, he concluded that whole blood transfusions were necessary in all forward medical installations. Also, about 20% of all casualties needed resuscitation, of these about 20% needed whole blood. This blood should be collected and processed in the theaters. The needed materials should be made available to accomplish this.

Even now, when his own special representative concluded that whole blood transfusions were vital in forward medical installations, the Surgeon General rejected the conclusions of this memo in November 1943. He remained firm in his belief that plasma alone was sufficient and that the instructions of May 1943 were adequate.

Although the Surgeon General remained focused on the use of plasma, others in the USA began to shift their attention to whole blood. By this time the Committee on Shock of the National Research Council made some steps in bridging the gap between the frontline experiences and the policies coming from Washington.

During the Second Conference on Shock, in December 1943, the National Research Council’s Committee on Shock still discussed “early and late shock”. It was found that both plasma and whole blood were effective, but that all patients in shock who had not been given whole blood eventually developed anemia (low red blood cell count). At this conference a letter by Major Henry K. Beecher, MC was quoted. Part of it read:

”Much too often the following sequence of events takes place: A man receives a bad wound; he bleeds; hours later his “blood” volume and pressure are restored by plasma infusions; the surgeon decides he is now ready for surgery; there is further loss of the too-small quantity of hemoglobin available in his body, as a result of the surgery; the patient’s circulatory system collapses and it is impossible to revive him. Plans are now being worked out for supplying whole blood for the forward areas.”

The messages sent from the front to this effect had finally reached Washington, although it took a whole year to do so. It led to the recognition that whole blood was a preferable treatment for shock, however, it was still recognized that plasma “had the advantage of convenience of transportation to areas to which whole blood cannot be taken.” Medical Department US Army, Blood Program in World War II. Page 35.

These conclusions slowly opened the door to a more realistic view on the need whole blood transfusion to treat shock in forward medical installation. In its subsequent report, the Committee shifted the focus even more to the need to use whole blood transfusions.

The Committee however was again slow in using the experiences in the field when it wrote about the amounts of plasma and whole blood needed to resuscitate a patient. In Shock Report No.17 (4 March 1944), the Committee did state that whole blood was the treatment of choice but that it should be given as follows:

“The first 500 to 1,000 cc of blood should be given rapidly. Subsequent administration should be at the rate of 500cc. per hour or less.” Medical Department US Army, Blood Program in World War II. Page 36.

Meanwhile, in the field doctors were often confronted with casualties who needed 500cc in the first 5 minutes and were given up to 20 pints in four different veins in 3 hours.

With the consensus on shock and its best treatment shifting to whole blood transfusion, by the end of 1944, the accepted best medical practice in the treatment of shock became:

“It is important for medical officers to understand that in the therapy of hemorrhagic shock plasma represents the measure which affects immediate survival of the patient until he can be stabilized and brought into more complete physiologic equilibrium by whole blood transfusion at installations where blood is available and its administration practicable.” Bulletin of the US Army Medical Department No.81 (October 1944), page 4.

Unfortunately, it would not be until July 1944 that the Surgeon General endorsed the liberal use of whole blood transfusions in forward medical installations.

Blood program in the ETO

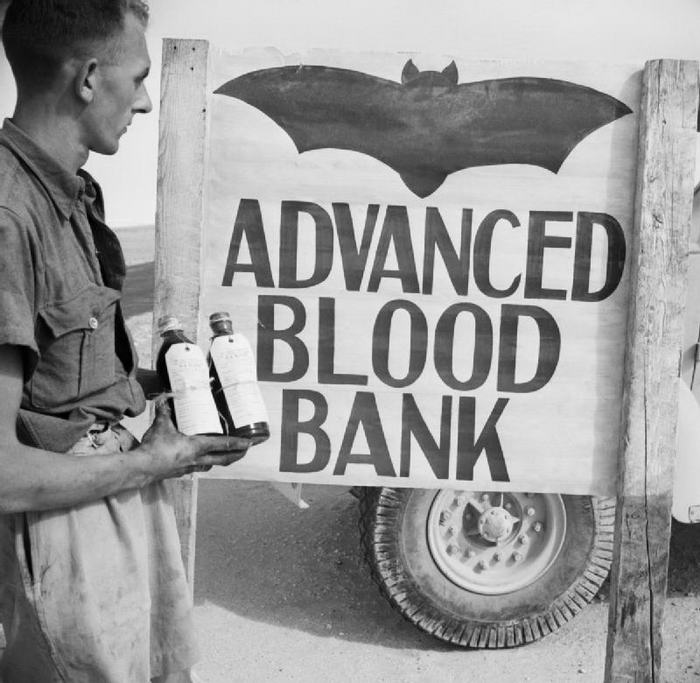

Using the experiences from the Mediterranean, the Chief Surgeon of ETOUSA, General Hawley, was quick to react. As early as April 1943, he authorized the establishment of blood banks in the General Hospitals in the UK. He also endorsed the transfusion sets developed by Emerson/Ebert.

Maj. Gen. Hawley:

Despite the May 1943 instructions of the Surgeon General, Hawley’s staff continue to make plans for a more elaborate blood bank system for the ETO. By early May 1943, his staff pointed out that rear area personnel and lightly wounded were possible donors, but that the biggest pool of possible donors were the people in the “Zone of the Interior” (the USA). In June 1943, following the instructions of the Surgeon General, Hawley concluded that blood used in the ETO had to be collected locally, as shipping blood from the USA was not an option.

With this conclusion, the staff started making plans and calculations for a working blood bank system for the ETO. Estimating the need for whole blood for the period of D-Day to D+90, the staff concluded that around 200 pints would be needed per day. This was roughly 1 pint per 10 casualties according to the estimates. They concluded that it was possible to collect this amount using rear area personnel volunteers. (Note the immense difference in these estimates and the conclusion of the 1943 Kendrick memo to the Surgeon General. Kendrick’s conclusions were that only 20% of the casualties needed resuscitation and only 20% of these needed whole blood or roughly 1 in 25 casualties).

It is also very interesting to note that General Hawley concluded that whole blood transfusion would not only be needed in forward hospitals (Field Hospitals and Evacuation Hospitals), in November 1943, he concluded that whole blood transfusions should be made available as far forward as the Clearing Stations in the divisions.

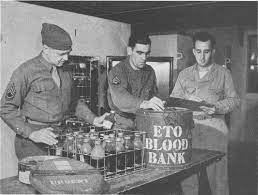

With all these parts of the plan in place, the 127th Station Hospital was designated as the theater blood bank for the ETO. Operating out of Salisbury, England this hospital was responsible for the collection, processing, storing, and shipping of all of the whole blood for the ETO. The 127th sent out collecting teams throughout the whole of the UK to collect pints of blood from volunteer donors.

127th Station Hospital personnel collecting blood, using the sets developed by the Army Medical School:

D-Day and beyond

Soon after the landings in Normandy, the estimated needed amount of blood per day and the 127th ‘s ability to provide it proved woefully inadequate.

The use of whole blood transfusions in the ETO soon increased towards a ratio of 1 pint of blood per casualty, rather than the estimated 1 pint per 10 casualties used in the plans. The doctors in the field quickly learned the vital role that whole blood could play in treating shock patients. Also, when there were many casualties waiting for an operation, the patients in this “surgical backlog” needed more blood to remain stabilized before they could be operated on. This effect was not taken into account when Hawley’s staff made its estimates.

Besides a more liberal use of whole blood than estimated, the number of rear-echelon personnel with O-type blood who volunteered to donate was also far less than expected. This effect became even stronger as more and more rear echelon personnel was transported to the continent, beyond the reach of the 127th Station Hospitals collecting teams. This effect on available donors was sadly also not included in the pre-invasion plans for the ETO blood bank.

By 12 July 1944, the ETO blood bank was supplying around 500 pints per day to the medical installations on the continent, working at its maximum capacity. It concluded that, even with an increased capacity (by paying donors for instance), it was not able to supply more than 700 pints per day. With the ever-increasing number of troops fighting in France, it was now evident that by the time Third Army was activated on 1st August 1944, 1,000 pints of blood per day were needed in the ETO.

General Hawley soon concluded that the only possible solution for this huge deficit of 300 pints per day was an airlift of blood from the USA to the ETO. This conclusion, and the calculations that showed the problem, were sent to the Surgeon General on August 5th, 1944.

Keeping in mind the long-lasting reluctance of the Surgeon General to help provide the necessary supplies and instructions for frontline use of whole blood, it is remarkable how rapidly the problem of the ETO blood bank was addressed and solved by the Surgeon General. It seems that his visit to Europe in July 1944 radically changed his opinion on the need for whole blood. Within a week of General Hawley’s message of August 5th, the Surgeon General replied that 500 pints of blood could be shipped to the ETO, starting on the 21st of August 1944!

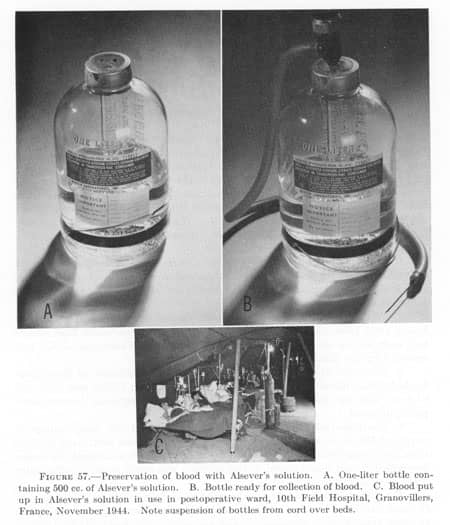

This was only possible by using Red Cross donors already donating blood in the blood plasma program. A number of the donations from O-type donors could be collected in bottles containing Alsever’s solution (a preservative of blood developed in 1943). It is noteworthy that these bottles were not yet being mass-produced at this time! Several manufacturers, understanding the urgent need, started the production immediately. American ingenuity again proved its worth!

The bottles, containing 500cc Alsever’s solution, could transport 500cc of whole blood. They were refrigerated during the transport to the airport. During the cross-Atlantic flight, they were not refrigerated, but as soon as the aircraft landed in Prestwick in Scotland they would be refrigerated again and transported to the 127th Station Hospital in Salisbury, England. From here, they were transported to the continent along with the blood collected locally. The initial tests showed that the blood transported in this manner was still usable for 21 days.

The first airlifted shipment of blood left the USA on 21st August 1944 as promised by the Surgeon General. It arrived in France on the 27th of August, 1944.

Distribution on the continent

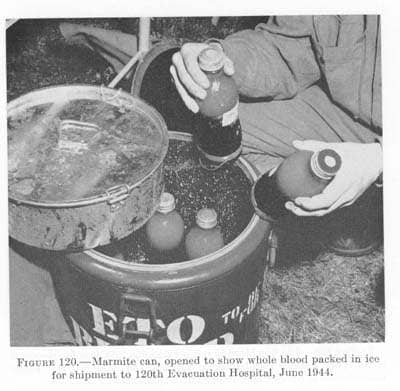

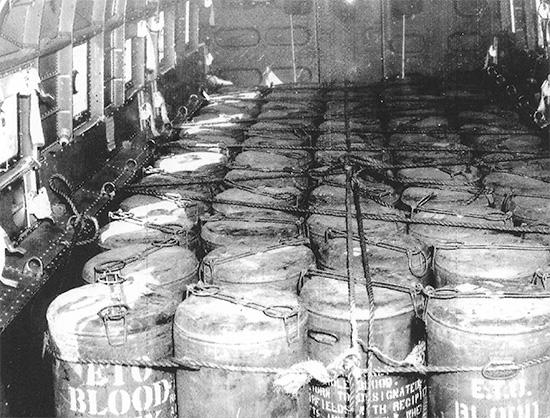

From the 127th Station Hospital, the pints of blood were taken from the refrigerated storage and transported in Mermite cans. These cans were normally used to transport food. Using one of the metal containers for refrigeration by filling it with ice, the blood was kept at a more or less constant temperature needed to maintain its usability.

127th Station Hospital personnel fill Mermite can:

Note that these bottles are not the bottles containing Alsever’s solution. They are therefore bottles containing blood collected locally in the ETO by the 127th Station Hospital.

From the UK, the blood was transported, first aboard the transport ships sailing to Normandy, later aboard C-47 cargo planes.

Mermite cans on board a C-47:

Mermite cans off loaded from C-47 at an airfield:

On 24th September 1944, the 152nd Station Hospital arrived on the continent where it assumed the responsibility on the continent of storing and transporting all the whole blood to the forward medical installations. It was located near Paris, where it remained for the rest of the War. From the 15th October 1944 onwards, the flights from the USA flew to Paris, delivering their cargo directly to the 152nd Station Hospital.

Each field army was assigned two detachments of this organization. These detachments were responsible for the shipping of the pints of blood from Paris to the forward medical installations of the army. The Third Army, for example, had Detachment D in the Communications Zone (COMZ) and Detachment C in the Army Zone assigned to it.

Blood was transported by specially equipped trucks and trailers, capable of transporting 1,000 pints of blood.

Also, several C-64 aircrafts were used to fly the blood to the front.

C-64 carying Mermite cans with whole blood:

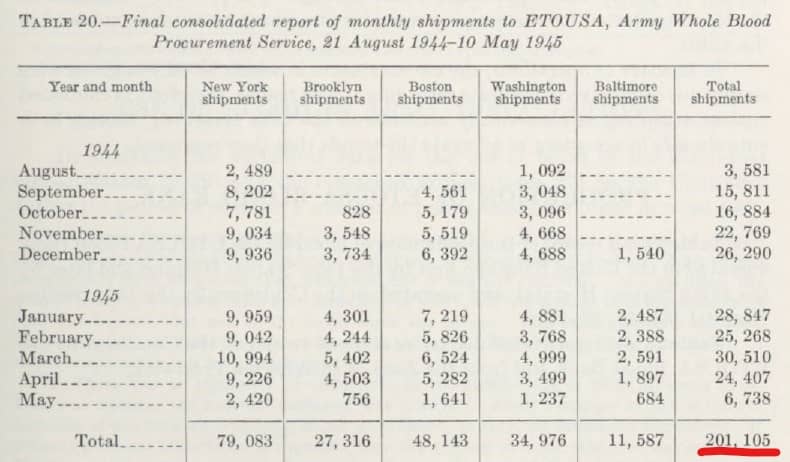

Between 21st August 1944 and 8th May 1945 a total of 201,105 pints of blood were airlifted from the USA to the ETO!

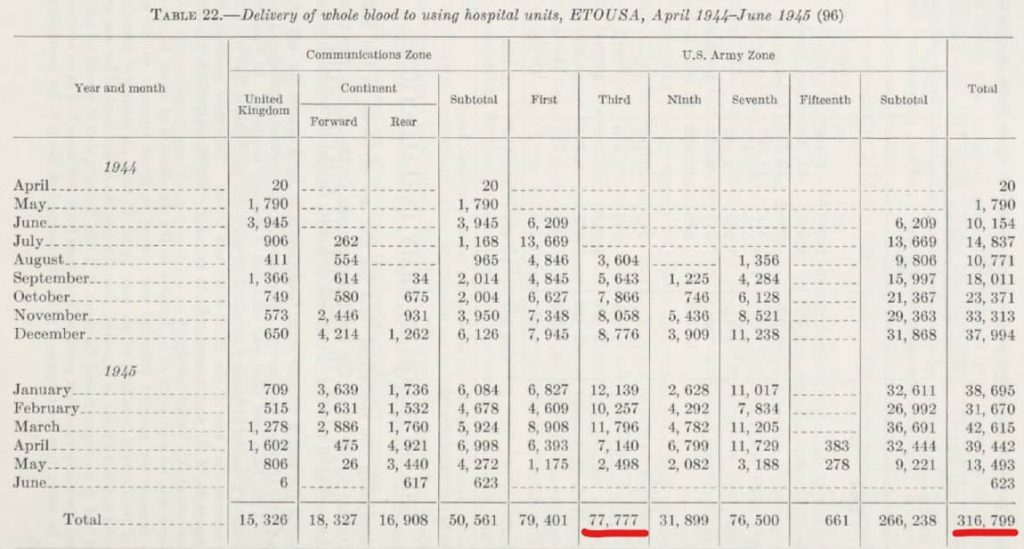

In the ETO a total of 316,794 pints of blood were given to casualties. Within Third Army, 77,777 pints were used during the War.

Whole blood in the 4th Armored Division

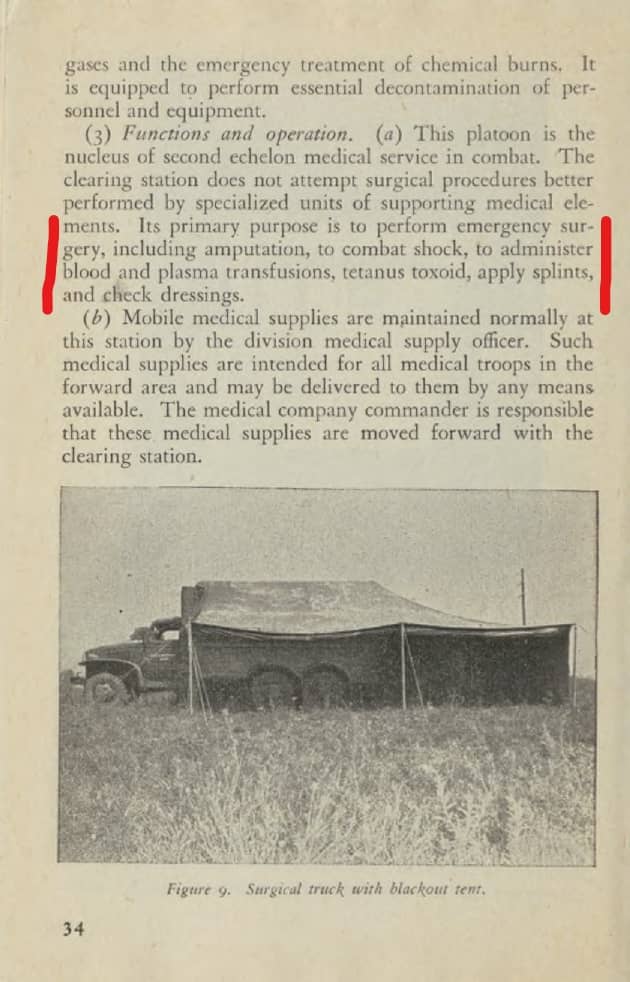

As noted, General Hawley became convinced that blood should be available as far forward as the Clearing Stations of the divisions. There is very little documentary evidence on this topic. It is interesting to note that it is mentioned in the TM 17-80 Armored Medical Units (1944):

TM 17-80 Armored Medical Units:

Within the documents in my collection there are only these:

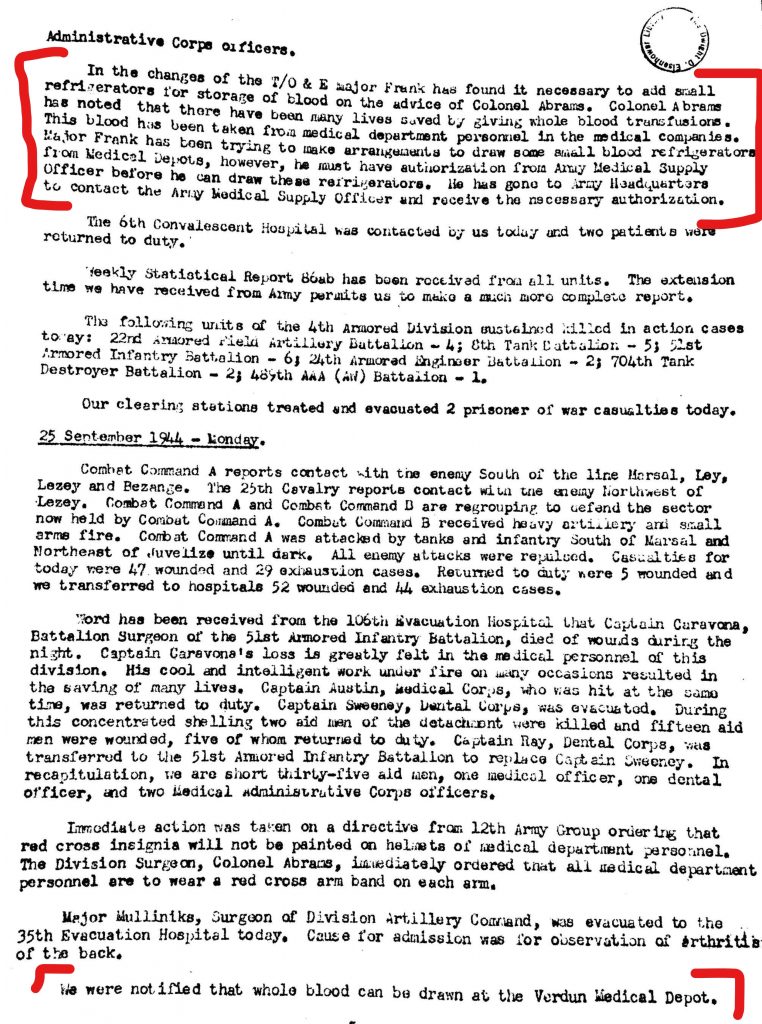

Division Surgeon Journal 24th and 25th September 1944:

The office of the Division Surgeon of the 4th Armored Division made some recommendations for changes to their TO&E (Table of Organization and Equipment) in September 1944, recommending the addition of a small refrigerators for penicillin and blood. On September 25th, 1944, the division was notified that it could start collecting blood from the Verdun Depot. This was blood stored in a way that it could be used even when not refrigerated. I strongly suspect that this is blood from the USA, in Alsever’s solution.

Division Surgeon’s report on 1944:

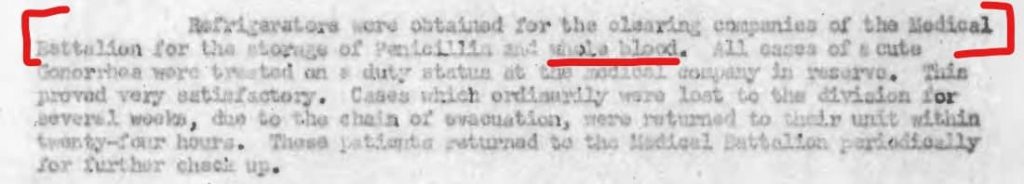

The report of the Division Surgeon for 1944 noted that at some point the division did obtain refrigerators to store penicillin and whole blood.

I have not yet been able to find any further evidence of the use of whole blood within the 4th Armored Division. Unfortunately I have not found any documents further proving the use of whole blood transfusions within the medical companies. Perhaps its use was somewhat limited due to the close presence of the 1st Platoon of the 16th Field Hospital. The presence of the Field Hospital Unit made the quick evacuation of the most severely wounded casualties possible. As these casualties were in the direst need of resuscitation it is possible that most of the resuscitation with whole blood was done at this Field Hospital Unit.

Regardless of the amounts of whole blood used in the 4th Armored Division, it is clear that the availability of whole blood for resuscitation in forward medical installations saved countless lives during the campaigns in Europe.

Pingback: Shock treatment in the US Army during WW2. Part 1: Shock and plasma. - Patton's Best Medics