The US Army in the European Theater of Operations (ETO) faced a tragic epidemic in the fall and winter of 1944/1945. Casualty numbers in this epidemic range from 46,000 – 71,000 soldiers (depending on whether only “pure” cold injury casualties are counted or casualties with other medical problems AND cold injury are counted). If we look at the higher number, the equivalent of almost 5 infantry divisions (of 15,000 each) had to be evacuated. If we take into account that almost 90% of the cold injury casualties were frontline riflemen (of whom about 4,000 were in each infantry division) the loss of fighting strength could be said to be as high as the equivalent of almost 16 infantry divisions.

What made it particularly tragic was that the epidemic was largely avoidable. This is the story of the trench foot and frostbite epidemic in the ETO.

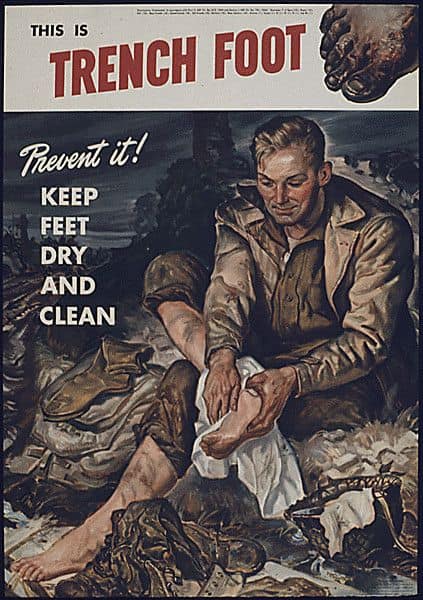

Trench foot / frostbite

Many factors play a role in the onset of trench foot and frostbite. To summarize them, we could say that it is the influence of adverse weather on the one hand and all the protective measures against this on the other hand.

The two main adverse weather factors that contribute to the onset of these medical conditions are prolonged exposure to cold, aggravated by moisture.

(The main difference between the trench foot and frostbite is the outside temperature. When the temperature drops below freezing, the term frostbite was used. The fact that the distinction between these two conditions was so small and relatively insignificant let the US Army to adopt the term cold injury, ground type after the War to describe all medical conditions caused by exposure to cold).

Unfortunately, the weather during the fall and winter of 1944/1945 in the ETO was dreadful. It was one of the coldest and wettest periods in recorded history in Europe. This, unfortunately, was beyond anyone’s control.

It should not have led to this number of casualties though. Proper winter clothing and boots available to the troops, proper instructions on the prevention of cold injuries, and rigorous enforcement of these instructions would have gone a long way in preventing this huge drain in fighting strength. Bad choices and bad timing created a situation where these protective measures were not (enough) available when the weather deteriorated, and then it was already too late. The US Army in the ETO had to relearn the lessons already learned in the Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTO) the previous winter, the hard way.

Winter 1943/1944 in Italy

During the winter of 1943/1944, the US Fifth Army fought in Italy, where it faced its own cold injury epidemic. Between September 1943 and April 1944, the Fifth Army recorded over 5,700 trench foot cases. In one week in February 1944 over 900 soldiers had to be evacuated because of trench foot. On average for every 5 battle casualties evacuated, 1 soldier had to be evacuated for trench foot.

These figures meant a significant drain on available manpower at the front. Before the next winter of 1944/1945, the Fifth Army took several steps to prevent trench foot. Among the steps taken were the requisition and distribution of shoepacs and the instruction of a large number of officers and enlisted men on the proper use of clothing and boots, the necessity of drying socks and inner soles, and instructions on how to keep your feet dry (standing on boxes and covering the floor of a foxhole with tree branches, etc.).

The total number of soldiers evacuated for trench foot in this winter was 1,572. A proportion of these cases turned out to be recurring cases. Soldiers who had suffered trench foot in the winter of 1943/1944 and had recovered, remained very sensitive to cold weather the next winter. One of the most important lessons learned was that only a very small proportion of the soldiers evacuated for trench foot were ready to return to full duty because of trench foot and its long-term effects.

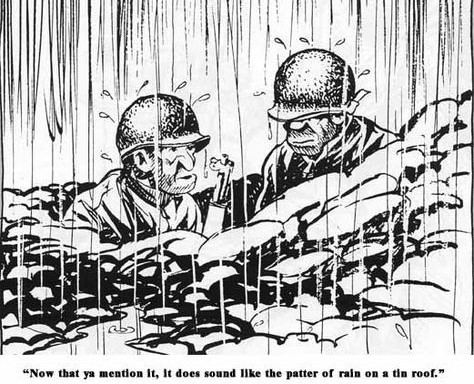

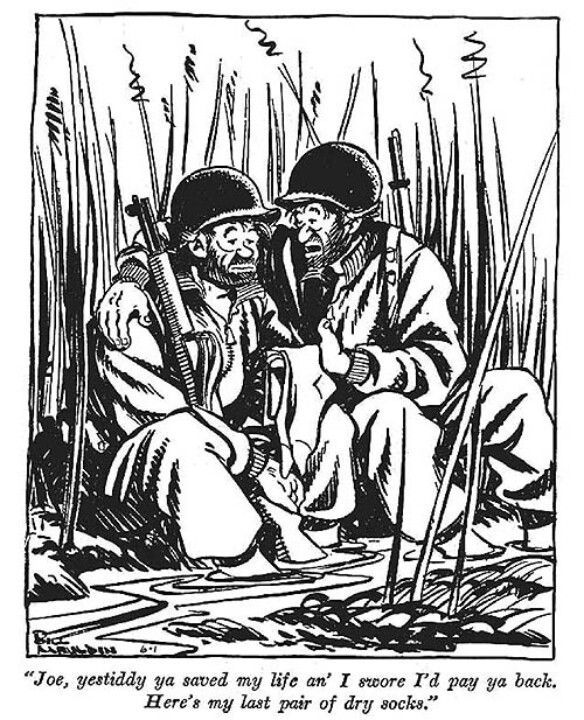

Bill Mauldin cartoon:

These hard lessons that were learned in Italy could have and should have played a major role in the decisions taken in the ETO in the preparation for the fall and winter of 1944/1945. Unfortunately, these lessons seem to have been lost to the ETO. The official report on the trench foot situation in the MTO of January 1944 only reached the ETO a year later, when its contents were no longer useful in preventing the epidemic.

The ETO

In the preparations for the campaigns in Europe during spring 1944, very little was done in preparing for cold weather. Many other things seemed and were arguably far more important during the preparation phase of the invasion.

By the time that preparations for cold weather had to be made to be effective in the fall and winter, other priorities remained. For cold-weather clothing to be in sufficient supply in the ETO for the fall of 1944, they had to be requisitioned and shipped there first. This meant a time lag of months between requisitioning and availability to the troops.

The first requisition for winter clothes from the ETO was made on 15 August 1944. It was for winter clothes enough for only one field army (by the fall of 1944 two Army Groups were fighting in the ETO under US Army command, consisting of 5 field armies).

By the time the cold weather seasons were coming, the allied armies were still racing across France and Belgium. Amongst the staffs of SHAEF and the 12th Army Group, there was a real sense that the War could be won before the winter if only the armies could push on. This led to an ongoing prioritization of the shipment of ammunition and gasoline over other items. As General Omar Bradley described it in his memoirs, he took a calculated risk by requisitioning ammo and gas and not winter clothes. Only after the armies had stalled on the German border were shipping priorities changed.

All these factors combined made the requisitioning and shipping of winter clothing a case of too little, too late.

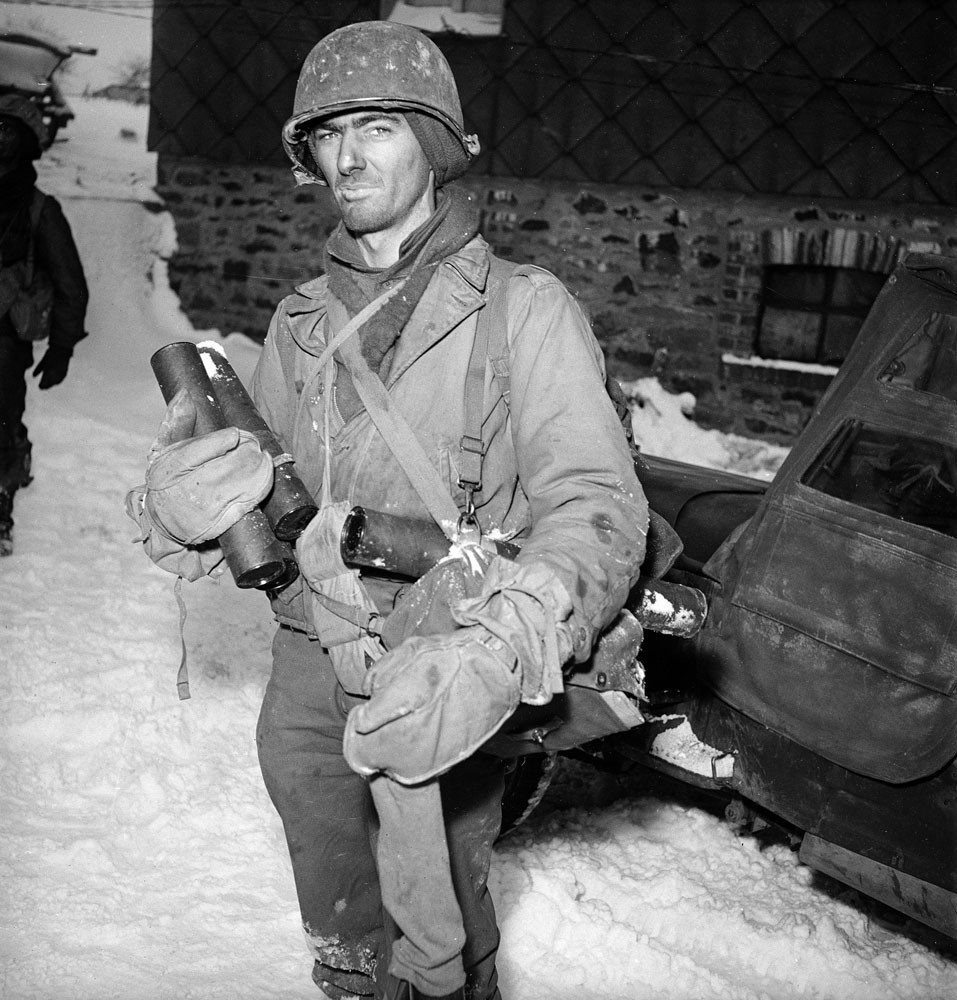

Soldier still fighting in his M41 uniform during the Battle of the Bulge:

Clothing

Besides ordering too few items too late, there was much debate about what to requisition. The Quartermaster staff in the ETO had their eyes set on the “Ike jacket” as a combat uniform, much like the British battle dress. The “Ike jacket” was to be worn with a woolen overcoat in cold weather.

This preference for the “Ike jacket” and overcoat led to the late acceptance of the M-1943 uniforms that were tested and approved at Anzio, Italy. The M-1943 uniforms had a liner that could be worn under the jacket in cold weather. The M-1943 was only accepted for general use in the ETO in November 1944 (t was accepted before this date for paratroopers, to replace the 1942 paratrooper uniform), when it became clear that the available overcoats were very unsatisfactory to the troops. They were too heavy, especially when wet, to use in combat.

Heavy overcoat:

The production and shipment of the ordered “Ike jackets” were unfortunately much delayed, so neither the “Ike jackets”, nor the M-1943 were available for issue to the combat troops until late in the winter of 1944/1945.

Another example of the ETO’s problems in requisitioning items is that of the sleeping bags for the soldiers. Each soldier initially was authorized four blankets. With the requisitioning of 2 million sleeping bags, expected to arrive in the ETO in September 1944, the number of authorized blankets was reduced to two per soldier. For this reason, the number of blankets shipped to the ETO was drastically reduced. By the middle of September, only some 57,000 sleeping bags had arrived in the ETO, leaving the troops with far too few blankets and sleeping bags to keep warm.

Footgear

The socks worn in the ETO were mostly cotton and light. The heavier woolen socks were not enough available to provide every frontline soldier with these socks when they became necessary to prevent cold injuries. By October 1944 a system was designed to provide frontline troops with clean dry socks regularly. By November 1944 the system that was chosen was a system of distributing these socks with the daily rations, mimicking the British system.

When the tactical situation prevented this distribution system from reaching the front, the men were left with the advice to change their socks daily and try to dry them by wearing them inside their shirts. Unfortunately, the same tactical situation preventing the daily distribution of socks often also prevented the men from changing and drying their socks. This added another factor contributing to the cold injury epidemic.

Bill Mauldin cartoon:

The standard combat boots worn in the ETO in WW2, they were the “rough out” type. They were not water-resistant, even when treated with dubbin. They were also often poor fitting. This was due both to a shortage in availability of certain sizes and the original fitting done wearing only thin cotton socks. This left no room for thicker winter socks. When heavier woolen socks were worn, the tighter fit reduced circulation in the feet. This was sometimes aggravated by misinformed instructions given to soldiers when they were told to lace their boots on tight to prevent trench foot. Reduced circulation in the extremities is one of the many aggravating factors in the onset of cold injury.

Standing or sitting in a cold, wet small foxhole with no room to walk, wearing these boots created the perfect storm for the cold injury epidemic.

The US Army did have two options in footwear that were meant to be worn in cold and wet circumstances. They were the overshoes and the shoepacs.

Overshoes

Overshoes (or galoshes) were meant to be worn over the combat boots. Because of rubber shortages, the tops were made of canvas. This made them less water-resistant and more fragile. There was a severe shortage of available overshoes at the beginning of the Cold Injury epidemic. By November 1944 Third Army only had enough overshoes to provide them to one soldier in four.

In a survey taken at the 108th General Hospital in the first week of the Battle of the Bulge 38% of the men with cold injuries had not received overshoes at all, 10% had received them too late to prevent cold injury and 12% had discarded them before combat because it was felt the overshoes had hampered their mobility. Even with 40% of the men admitted with cold injury during this week having been provided with overshoes only 11% stated that they had been able to keep their feet dry, reflecting poorly on the quality of these overshoes.

Medic wearing overshoes:

Shoepacs

Shoepacs were by far the best option available, especially when properly worn with heavy woolen socks and felt insoles. Unfortunately, the ETO decided too late to accept them for the issue to the troops to have them shipped and distributed in time to be effective. Also, the initial requisition of fewer than 500,000 pairs was too small to provide them to every soldier.

Interestingly, the US Seventh Army, fighting its way from the south of France through the Rhone river valley, was much better equipped with shoepacs. This was the result of the Seventh Army’s supply base coming from the Mediterranean and thus making full use of the MTO’s experiences.

Shoepacs:

Treatment

The treatment of Cold Injury was very time-consuming. Only the mildest cases were treated in the first two echelons of the evacuation chain. Most cases had to be evacuated to one of the evacuation hospitals. Here the treatment consisted first of keeping the feet cool (room temperature or lower) to prevent hyperemia and swelling as it was discovered that these physiological reactions to rapid warming of the feet would only increase the damage done to the tissues. Gradually, as the feet began to recover, the patient was allowed to begin walking short distances. This convalescence schedule was expanded as the pain of the feet permitted. It would often take weeks or even months before a patient was able to be returned to duty. And then most were returned to limited duty only.

Many different sorts of treatments were tried to speed up the recovery process, but none proved to be of any significant benefit. It was a process of the body trying to heal itself. The average number of days lost to duty for cold injury was 83 days per soldier.

Prevention

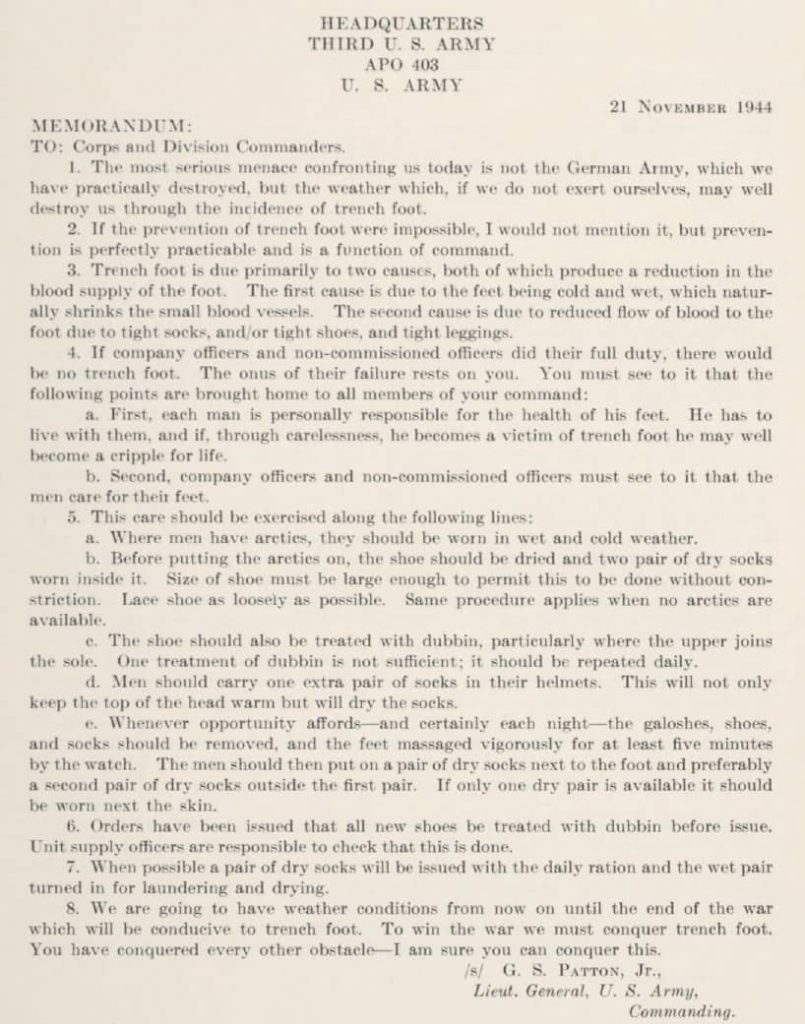

By the time that the epidemic showed itself to be a grave problem, the armies in the ETO started to take notice and reacted to it with a series of measures aimed at prevention. The Third Army issued its first directive on 9 November 1944. General Patton followed this directive with a letter on the 21st November 1944 to his commanders. It began with the blunt statement that: “ the most serious menace confronting us today is not the German Army, which we have practically destroyed, but the weather which, if we do not exert ourselves, may well destroy us through the incidence of trench foot”.

Patton’s letter:

A full prevention program was initiated in January 1945 all across the ETO, making the prevention of cold injury a command responsibility. The program consisted of the instruction of the troops on preventing cold injury by keeping feet warm and dry. Control teams were created in units to enforce these measures. Whenever possible, soldiers were rotated out of the frontline for a few hours to get warm and dry.

The effects of these measures are difficult to assess as the weather in the ETO improved by March 1945. It does seem that they had some positive effects on reducing the number of cold injury casualties. It is very interesting to note that the General Board on Trench Foot (Cold Injury, ground type, in 1945) did not include them in their recommendations. Almost all the recommendations were on the development of proper combat boots and socks underlining the preventable character of the epidemic.

Purple Heart

One of the byproducts of the cold injury epidemic was the discussion of medals. Should casualties from cold injury be awarded a Purple Heart? The Army Regulation 600-45, dated 3 May 1944 stated that “an injury to any part of the body from an outside force, element or agent sustained as the result of a hostile act of the enemy or while in action in the face of the enemy” would qualify a soldier for the Purple Heart. The word “element” was interpreted as including weather influences. Much discussion was the result. As cold injury was seen as a preventable problem it was felt that casualties from it should not be awarded a Purple Heart. Some even suggested that they should rather be punished. In the end, it seems that soldiers suffering from severe frostbite were awarded the Purple Heart, most of the other casualties from cold injury were not.

Cold injury in the 4th Armored Division

Like all other US Army units in the ETO, the 4th Armored Division was severely affected by the cold injury epidemic, although perhaps not as severely as many infantry divisions.

The division too had to deal with inadequate supplies of protective clothing and equipment.

Activity Report Division surgeon 1944:

And it also had to fight in terrible weather conditions, as we can read in these 10th AIB history quotes:

This was part of the entry for November 8th, 1944. It was the day before the 4th Armored Division went on the offensive again after a short period of rest. It is no coincidence that the first reported case of trench foot in the 4th Armored Division was on the 9th of November, 1944. Unfortunately, these weather conditions continued throughout the Lorraine Campaign as is shown by this example from the 10th AIB history, dated November 16th, 1944:

Even before the onset of cold weather, the medical personnel of the 4th Armored Division was instructed on the prevention of cold injuries as we can see in this entry in the Division Surgeon’s Journal for the period of October 7th to November 8th, 1944:

Unfortunately, these instructions were not enough to prevent the number of trench foot cases to rise dramatically.

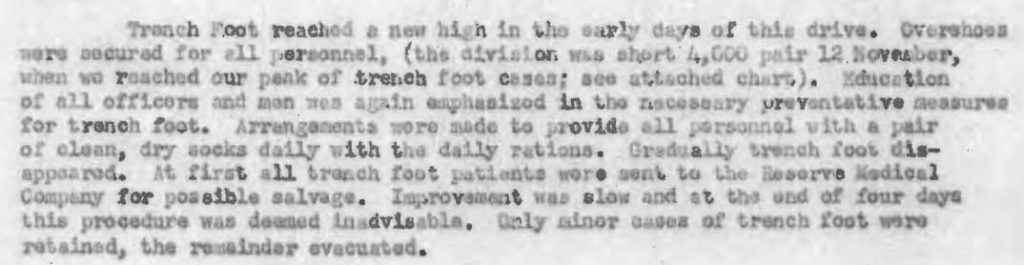

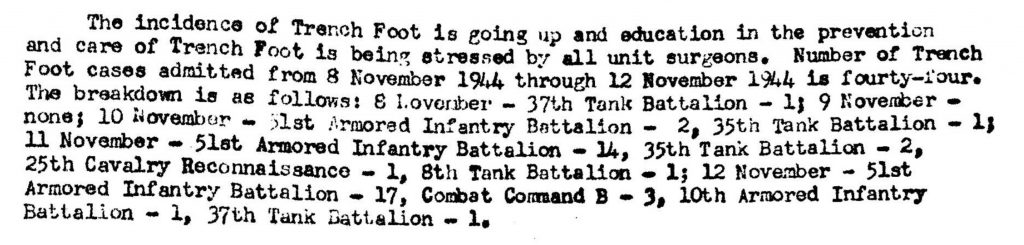

Division Surgeon Journal 12th November, 1944:

Responding to the increasing numbers of trench foot cases in the division, the shortage of overshoes was addressed and a program of instruction was initiated, possibly encouraged by the November 21st letter from Patton. Also when possible, the men were offered moments to warm up and rest. With these actions taken, the number of new trench foot cases began to drop.

Division Surgeon journal 28th November, 1944:

Lt. Col. Abrams, the Division Surgeon, was convinced that despite the drop in cases by these actions, better combat boots were required to fully address the problem (much like the conclusion of the General Board in 1945).

Division surgeon journal 20th November, 1944:

In January 1945, as the division was resting after the Battle of the Bulge, the activities to prevent cold injury were enhanced by supplying shoepacs and by the creation of trench foot control teams, much like the other units in the ETO as we have seen.

Activity Report Division Surgeon 1945:

An attempt was made to treat trench foot cases within the Reserve Medical Company in the hope of returning them to duty as soon as possible. As we have seen, the treatment or recovery from cold injury was a long process so this hope soon changed to a more realistic policy of evacuating all but the lightest of cases.

Division Surgeon Journal 4th December, 1944:

Activity Report Division Surgeon 1944:

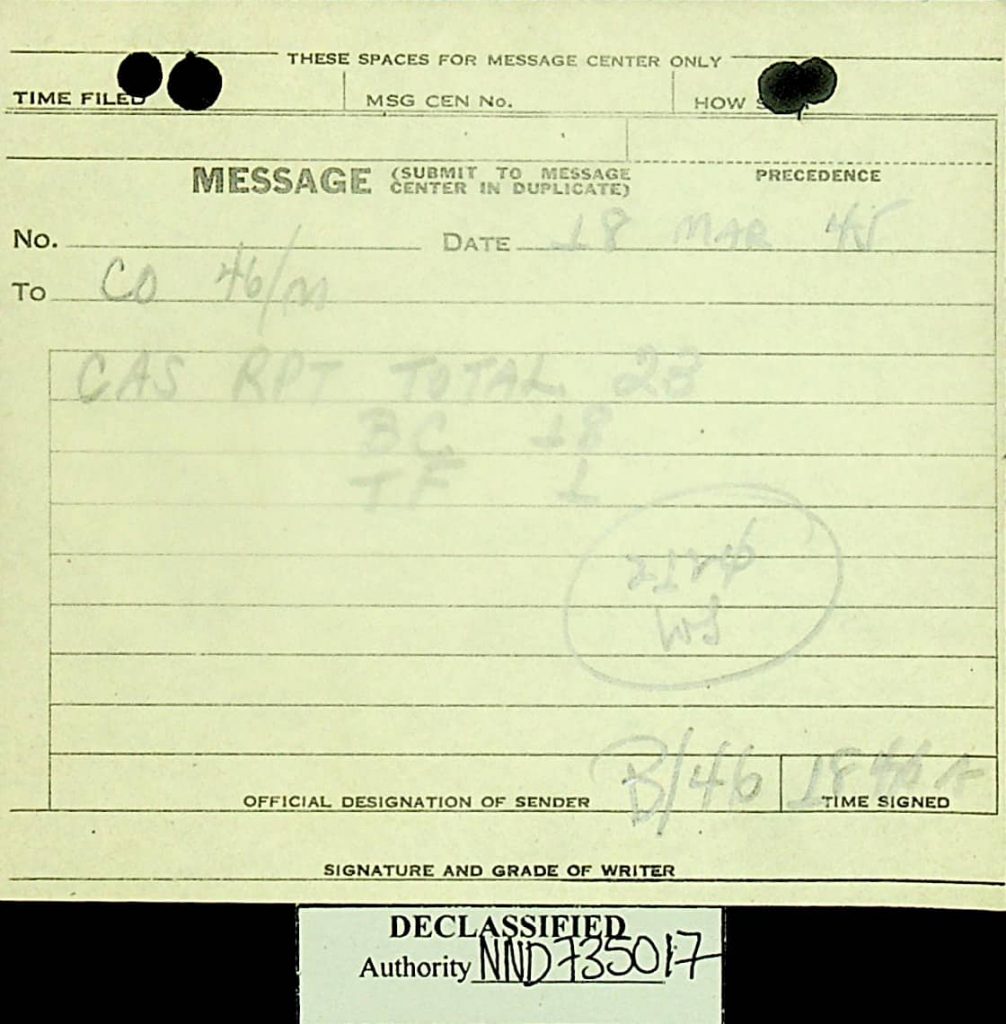

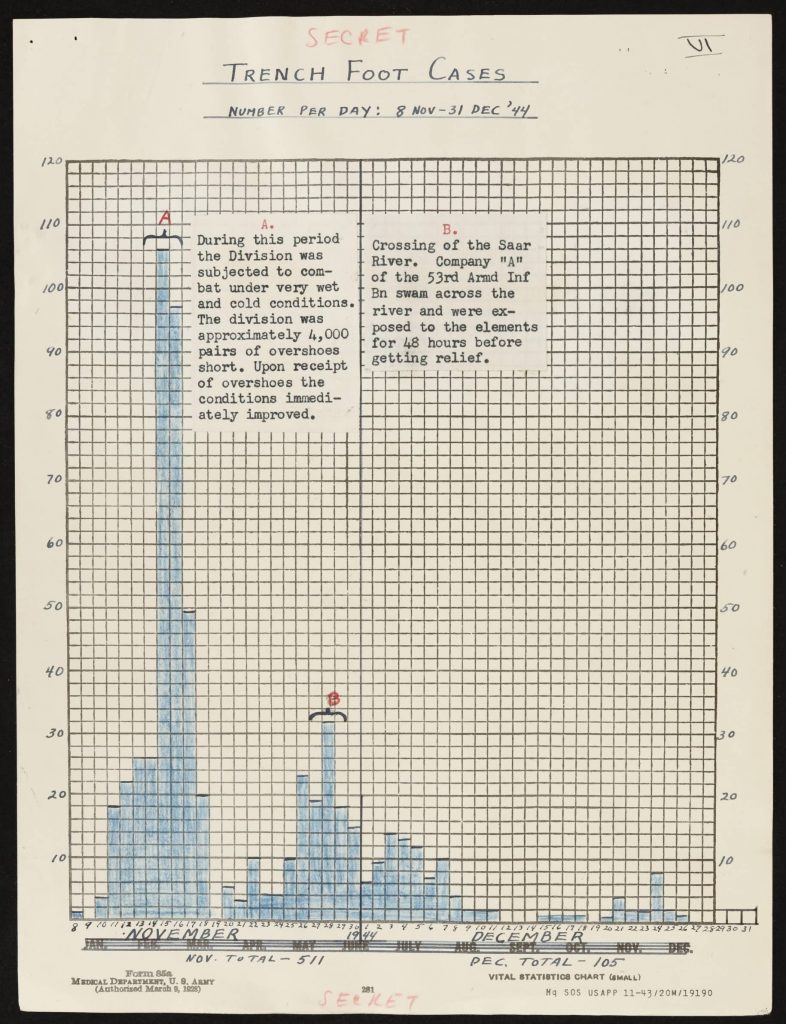

The first frostbite case was reported on December 23rd, 1944 when the temperatures had dropped below freezing long enough to freeze the ground solid.

10th AIB history 23rd December, 1944:

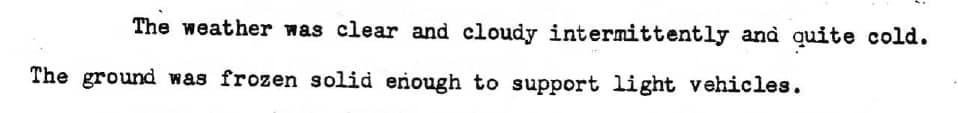

This change in temperatures was the reason that all medical companies in the 46th Armored Medical Battalion were ordered to change from trench foot to frostbite in their reports on December 25th, 1994.

Message 46th AMB December 1944:

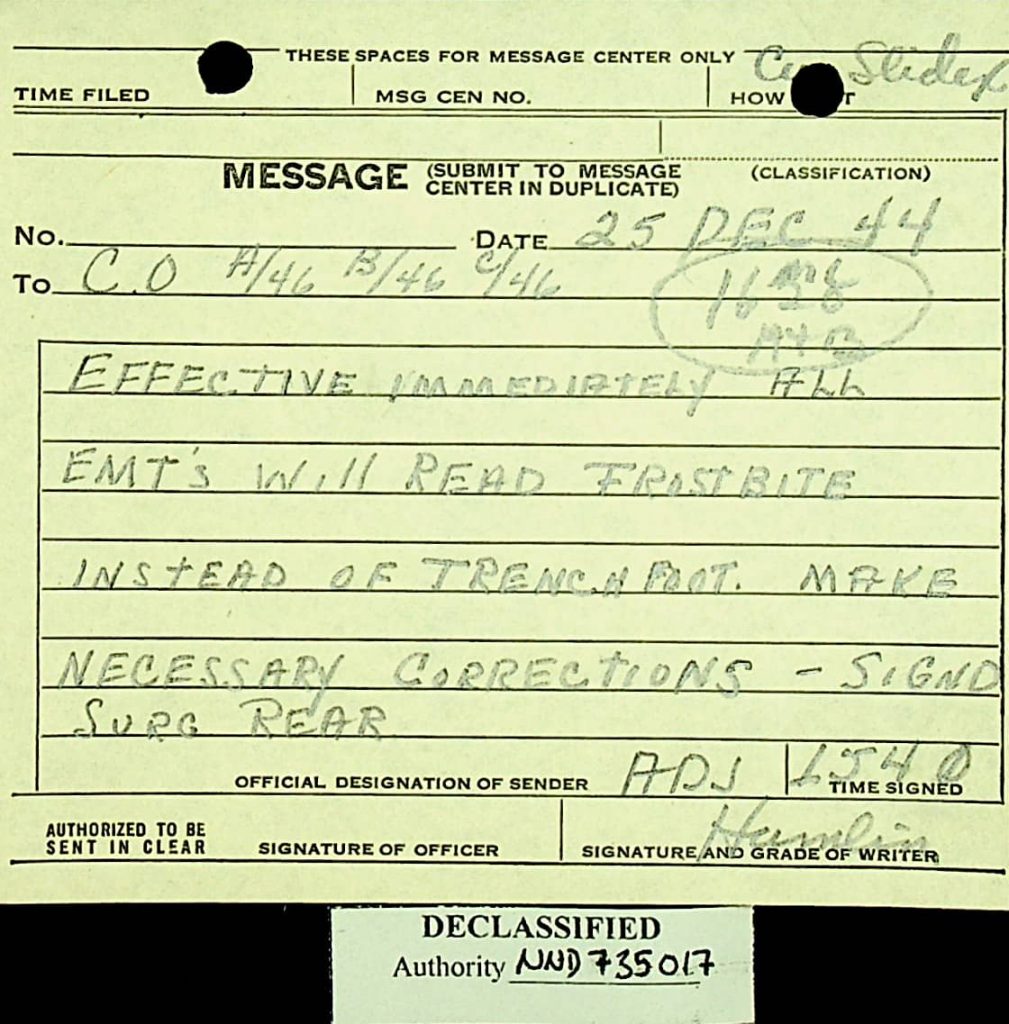

The last reported case of frostbite that I have found, was reported on January 11th, 1945.

Message 46th AMB January 7th, 1945. FB means Frostbite:

After this date, the 4th Armored Division moved to the border region between France and Luxemburg where the men were billeted in houses. The division started its next offensive in the last days of February 1945. By this time the weather was more moderate, with temperatures above freezing.

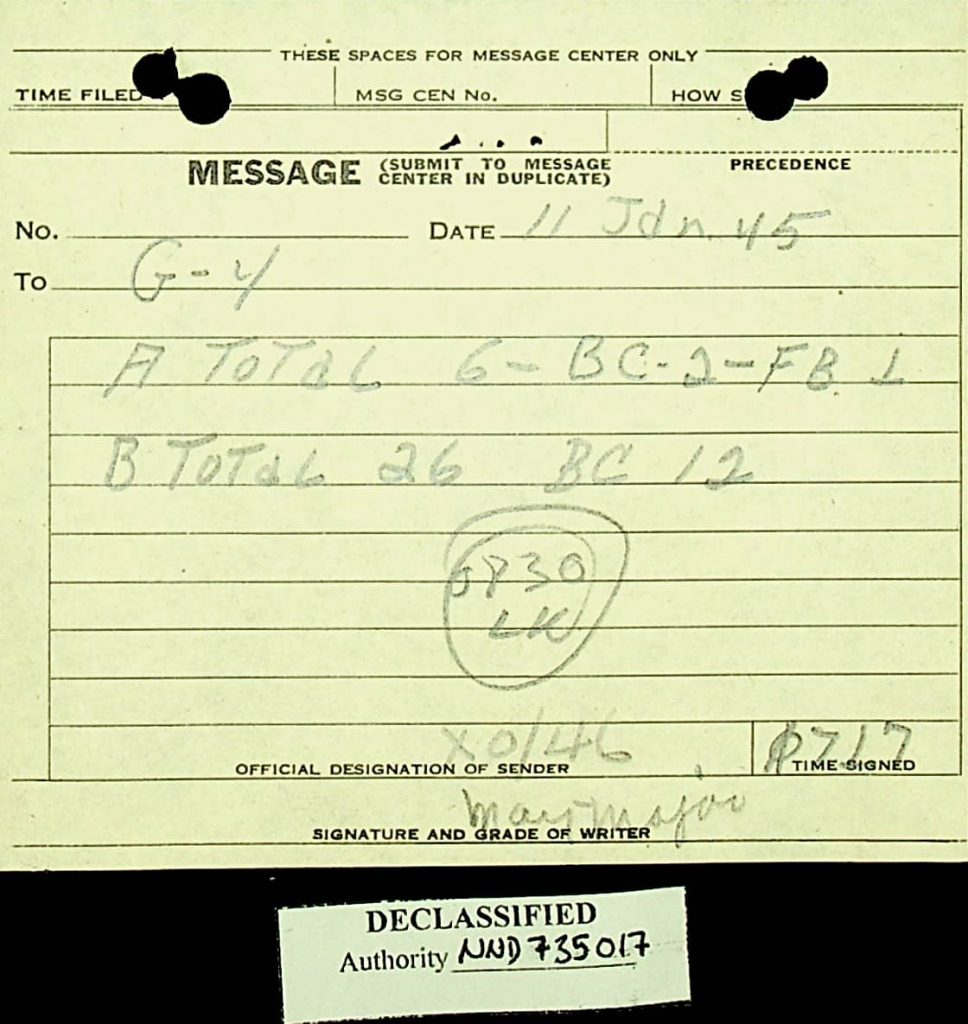

The last reported trench foot case that I have found was on March 18th, 1945.

Message 46th AMB 18th March, 1945:

Total 4th Armored Division cold injury casualties

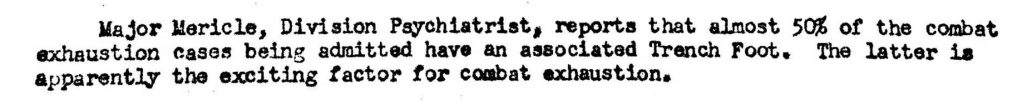

It is very difficult to come up with a definitive number of cold injury cases. This is partly because I don’t have all the records yet. The other reason is that, as we have seen in the introduction of this article, reported cases are of soldiers who were evacuated for cold injury. Many others were evacuated for other medical reasons, like combat exhaustion, but were also suffering from cold injury (50% of the combat exhaustion cases).

Division Surgeon Journal 16th November, 1944:

When we take the total numbers of cases in the ETO (46,000 vs 71,000 cases), we can see that this second reason might increase the total number by as much as 50%.

For 1944 the Division Surgeon, Lt. Col. Abrams, reported these statistics:

So, for 1944 the total number of reported cases of trench foot is 616. The total of cases of frostbite for 1944 is 139.

For Frostbite, the numbers for the period of January 1st to February 22nd, 1945 were 148 cases:

During the period between February 25th and March 18th, 1945 an additional 18 cases of trench foot were reported by the medical companies.

This would make the total number of trench foot cases in the 4th Armored Division 634 and the total frostbite cases 287.

The total of cold injury casualties reported in the 4th Armored Division is therefore 921. With a division strength of around 11,00 men, this means some 8,3% of the total manpower of the division or roughly the entire strength of an armored infantry battalion!

With the aforementioned potential underreporting of cases of perhaps 50%, the total number of casualties might have even been closer to 1350. This represents about 12,2% of the entire manpower of the division. This was thus a huge drain in fighting strength during the period of the War where the 4th Armored Division had some of its toughest offensives.

When we consider all the consequences of this drain such as the additional strain on the men left on the line, the need to rush often ill-trained men to the front as replacements, the additional strain on the medical services, only then can we begin to understand the full tragedy of this terrible epidemic.